On a hot and sunny Monday afternoon, about 50 young demonstrators, many Black and brown, marched through downtown Grand Junction. Several football players from Colorado Mesa University were in the crowd. Head coach Tremaine Jackson was in the back.

This is about standing up for George Floyd, Jackson said, and it’s also about standing against the racism they experience in this community.

“This issue is something that I live with daily,” said Jackson, who is Black. “I just happened to be the head football coach here and so we're not gonna run from the issues at all. We just want to address it, make sure it's acknowledged and, and form a plan to move on.”

There were some stares as the protestors moved down Main Street, but also encouragement. One white man pointed to the toddler at his side and said this was what he wanted to teach her. Others in this majority-white town on the Western Slope walked out of their shops and waved.

While protests around Floyd’s death have brought dramatic images of confrontations between protestors and cops, this was something different. The group was headed for the Grand Junction police station, but not for conflict.

Coach Jackson and Police Chief Doug Shoemaker had already been talking for days.

“We're planning on kind of setting an example and addressing some of the issues that we need to address, quite frankly,” Shoemaker said.

Jackson had reached out to him after the chief wrote a long thread of tweets condemning Floyd’s death.

“So we're going to do it as a team, one team. And I think once we start respecting the rights of one another and we start talking about those things openly, maybe we can be an example for other places,” Shoemaker said.

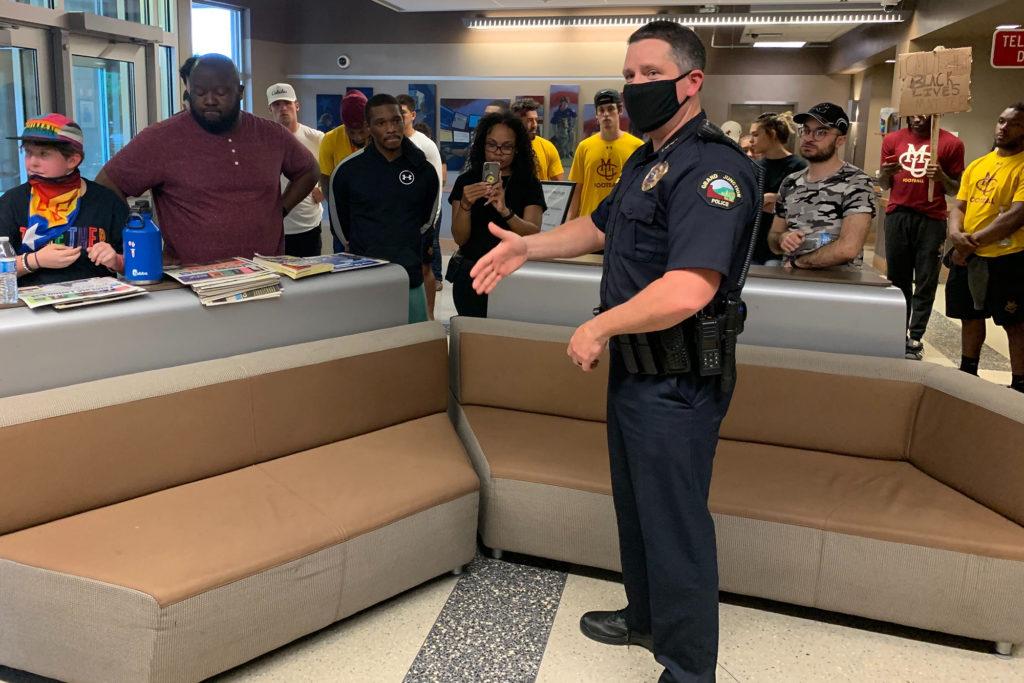

Inside the police station, things quickly went from kumbaya to something much more complex as the chief took questions from the crowd. One young Black man said he’d personally seen injustice from Grand Junction police

“I need action,” he said, bluntly. “I don’t want to talk.”

He questioned why it took a tragedy to address the issues he believes are in the department.

“How long have you been on the staff?” he asked Shoemaker. “We could have been talking.”

He then walked out and a small group followed him. Coach Jackson told his players to stay put, and they did. Others in the room were still frustrated.

As people shouted in anger, the coach stressed in his booming voice the need to have a civil conversation with the chief.

“I’m saying he’s going to acknowledge that there is a problem,” he said. “Chief, have you acknowledged that there’s a problem?”

“A big problem,” Shoemaker replied.

“He’s acknowledged it,” Jackson said. “And I think that’s what we need, man.”

Shoemaker then told the group that one way that they can make a difference is to join his department themselves.

“Seriously. It’s an open application process all year round,” he said.

Shortly after, one of the young Black men walked up to him, shook his hand and asked for someone, anyone to take a photo.

“I don’t know what the plan is,” the young man said. “But this is a first step.”

Shoemaker then asked him and everyone else in the crowded lobby to hold him accountable for making his department better.

“And give us some time. This is not an overnight thing,” he said, as people took photos and filmed with their phones. “This is a marathon, not a sprint. But my pledge to you, on film, and even on our own department film, is that hold me accountable.”

That includes Jackson, who said the two of them are going to start having regular talks about shifting the culture of racism — with two conversations this week alone.

“We’re going to meet as many times as we need to meet in order to make change,” the coach said.

Then, he and his players headed home.