In the weeks before he got sick, Jason Jahanian was on the move.

He road-tripped through Arizona with his wife Michelle and their kids, visited slot canyons, rode side-by-side ATVs and did a boat tour of Horseshoe Bend on the Colorado River. As they traveled, local events started shutting down around them: COVID-19 had come to America and everyone would soon be affected.

After he got home to Lone Tree on March 20, Jason began to feel ill. It all started with pressure and pain in his chest. Michelle, a nurse, brushed it off. Jason had been anxious about a few things and she thought it was just his nerves. But he started coughing and it quickly got worse.

“At that point we knew that it was probably COVID,” she says.

When Jason first got sick, there were fewer than 200 cases of coronavirus reported in the state. Later, revised numbers showed that the disease was spreading quickly; the actual case number was much higher and growing.

Still, Jason seemed like an unlikely COVID-19 case: He was young, healthy and rarely got ill. At the time, officials were mostly focused on older people or people with diseases that compromised their immune system or heart. Jason didn’t meet any of those criteria. But as he got sicker, his story became a cautionary example of how little is still known about who gets sick and why. And his case became a test of the medical providers fighting a disease they hardly understood — and the vast resources it can require to beat it.

The family had no idea where he picked it up.

“It's everywhere. You can get it from walking by someone,” Michelle says. “We have no idea.”

Michelle works in an infectious disease clinic and she had the tools she needed to track Jason’s health at home: a stethoscope and an oximeter, which measures oxygen levels.

His lungs sounded worse by the day, and his oxygen levels dropped.

“Just walking to and from the bathroom, a whole 15 feet, he was getting winded,” Michelle says.

The chest pressure faded after a couple of days and the fever broke, but for days, he couldn’t shake the exhaustion. Then his oxygen levels plummeted and Michelle knew she couldn’t help him anymore at home.

At 2 a.m. on Thursday, April 2, she brought him to the emergency department at Sky Ridge Medical Center in Lone Tree. He was one of 1,422 Coloradans who'd required hospitalization by then and one of more than 180 reported hospitalized that day. The number of people in Colorado sick enough each day to need hospitalization would climb past 200.

“The hardest thing I've ever done was to watch him walk through those doors and I could not go in,” Michelle says. “So I had to trust that those doctors and nurses were taking over care. And there was nothing I could do.”

In most COVID-19 cases, those closest to the patient are in the dark. Most hospitals block visitors from seeing patients for fear of infections; and the behavior of the disease is still mysterious enough few civilians know what the right path forward is. Many families haven’t discussed what to do with a family member when they get severely ill, how much to intervene and when to let go. On top of that, many are navigating an overwhelming medical system, making decisions about care on the fly, and often with little information and time.

But here, Jason was lucky. As a nurse, Michelle knew when his conditions worsened enough for him to go to the ER, something a person without medical training might have missed, and understood the treatments, the options, the care.

Once in the ER, Michelle thought his providers would give Jason some oxygen and release him within a day or two; they texted back and forth about his condition throughout the first day. But within a couple of days, the hospital called and told Michelle his condition had grown more worrisome: They had to put Jason on a ventilator.

“At that point I knew how critical this was, and they relayed what his lungs, his x-rays looked like,” Michelle said.

Michelle could no longer talk to him and hear how he was doing.

But unlike most people with a sick family member, Michelle had an advantage.

“I had worked at that hospital (Sky Ridge),” she said. “I had lots of eyes inside the hospital. My doctors that I worked for were consulted on his case. And so they were also laying eyes on him and calling me.”

“She's a nurse. She gets it,” said Caroline Melton, one of the nurses who treated Jason.

What’s more, Michelle's sister is also a nurse who works on the coronavirus team at a hospital in Los Angeles, which had seen more cases at that point. So her sister was in touch with doctors there, and they all collaborated on Jason’s care.

The morning after Jason was put on the ventilator, Michelle was sitting at her kitchen table and their eight-year-old daughter Kestin came downstairs. Michelle knew she had to have a frank discussion about Jason’s condition. Family members were already on their way to help and Kestin would know that something was wrong.

Michelle says she told Kestin, “Daddy has gotten a little worse overnight and was on a breathing machine.” She explained Jason’s mom and sister-in-law were going to come visit.

“We just need to keep praying for Daddy to get better,” she remembers saying.

“Promise me that he’s coming home,” Kestin responded.

“I can’t promise you that, but I can promise he is fighting as hard as he can because he wants nothing more than to be home with us and loves you more than anything,” Michelle says she told Kestin at the time.

In the hospital, Jason’s chest X-rays kept getting worse. His doctors told Michelle they could not see the outline of his lungs.

“They call it a whiteout,” she said.

Normally when you take in a deep breath, the air filling your lungs looks dark on a scan. Jason’s were not expanding to get the air into them; on a scan, they just looked white.

There was nothing else Sky Ridge could do. Jason needed more intense medical care than they could provide, so they decided he needed to go to another hospital, The Medical Center of Aurora. The cardiac surgeon on call there that day was Dr. Jennifer Hanna; she was the one to review his case and figure out what else they could do to save him.

“People assume that people with just poor immune systems like young children and the old were really the vulnerable patients,” Hanna said. But Hanna says there’s a whole group of people in their thirties and forties that is also “getting really, really deathly ill because their immune systems are so good. Really this age group that thinks they're kind of invincible are very vulnerable.”

That’s the category Jason fit into.

“I mean we're talking about a man that is the epitome of health,” Michelle says. “For his 40th birthday, he walked slash ran 40 miles. I mean, we're talking, he doesn't drink, doesn't smoke.”

Before catching the coronavirus, he'd spent just one night in the hospital in his life, when he had his appendix taken out in high school, 25 years ago.

Jason’s illness underscores the unpredictability of a virus that’s triggered a global public health emergency. One theory is that in younger patients like Jason the disease unleashes what doctors are calling a cytokine storm: They catch the virus and their immune system kicks into overdrive and attacks other organs. Another theory is that genetics can make some people more vulnerable to the virus.

Hanna says the disease is scary for doctors because research is still evolving and doctors have no idea how it will act. And it often moves quickly so they have little time to respond.

“We just don't know much about it. We didn't know what to do to treat it,” she says.

Jason was already on a ventilator, but Hanna and her colleagues thought a different kind of machine might help, too: ECMO, which stands for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. It’s a life support machine for people with severe illnesses that prevents their lungs or heart from working properly.

“We're just bypassing the lungs,” Hanna says. It takes the blood out of the heart, oxygenates it and then pumps it back into the rest of the body, keeping it alive and allowing the lungs to rest and heal. It’s been described as the most aggressive form of life support available, a last-ditch approach doctors will only try on some patients — generally those who are younger, not struggling with other underlying health problems and seem to have a better chance of survival.

“It's a lot of tubing. If you walk into a room, you'll see him hooked up to a ton of stuff,” Hanna says.

There’s a monitor on his forehead keeping track of how sedated he is, a line into his neck with medication, tubing into his groin for the ECMO and into his mouth for the ventilator, and a blood pressure monitor on his wrist.

She and the other doctors were cautiously optimistic about Jason’s chances for survival, but it’s never clear how a patient will respond to treatment.

“We have patients on for weeks before they either recover or don't,” Hanna says. “Our staff can become demoralized seeing these patients sort of sit there on ECMO for days on end without it seeming like anything's improving.”

Michelle meanwhile knew exactly what the ECMO meant, a downside to knowing the medical system.

“That was our last saving chance. If this didn't work, nothing was going to work,” she says. “I heard the doctors say ‘dire straits.’ I mean, I knew, I knew.”

For days, there were no major signs of progress. Doctors wanted to try several experimental treatments. First, they suggested a drug called tocilizumab, which depresses the immune system, putting Jason at risk for a secondary infection but also potentially quieting the immune storm inside his body. They also suggested convalescent blood plasma, where blood from people who recovered from COVID-19 is pumped into the patient, to help provide antibodies that might fight the infection.

Each time, Michelle had to decide "yes" or "no," with Jason’s life hanging in the balance.

On the day before Easter, a week and a half after Jason entered the emergency room, she broke down.

“I felt like I had to give everything to God because I had so much anxiety,” she says. “I just had to ask him to help me and guide me on this path and to make any available treatments that Jason needed available to me.”

The next day, Easter Sunday, the doctors called and said he was approved for the trial study to do the convalescent plasma.

The disease takes a toll on those who treat it, too.

At The Medical Center of Aurora, doctors and nurses were seeing a lot of really sick patients, and they were seeing a lot of patients die, a heavy mental weight to carry around. Melton, one of Jason’s registered nurses, estimated a COVID-19 patient like Jason could have more than a hundred people contributing to his care: nurses, doctors, physical and occupational speech therapists, dieticians, housekeeping.

“It takes an actual village and I was just privileged to be a part of that,” she says.

For Hanna, Jason’s illness came at a critical moment in her own life. She was just returning from maternity leave and Jason was her very first patient.

Her son Brooks was about 8 weeks old and she says she worried about bringing the virus home. As soon as she’d walk in the door, she’d want to hug her child. But the first thing she’d do is disinfect everything, take off her scrubs and take a shower.

“So it's kind of an interesting time to actually be away from home,” she says.

There is no comprehensive accounting of the healthcare workers who’ve died of COVID, but an investigation from Kaiser Health News and the Guardian found more than 600 frontline providers likely died from the disease, many of them people of color. A doctor in New York died by suicide after treating COVID-19 patients; a Colorado paramedic who answered the call to help in New York in midst of an outbreak there died from the disease.

On top of that, Jason shared so much in common with Hanna's husband: They’re the same age, both really fit, with young children.

“It was really scary. I actually kind of held a lot of that back from discussing with my husband,” she says.

Amy Cooper, one of the nurses who treated Jason, has worked in intensive care units for ten years but even so, managing patients who are fighting to survive COVID-19 has been tough.

“Several die, several don't make progress, but very few have been success stories,” Cooper says. “It sort of boggles my mind how this virus picks and chooses people, and who gets really sick and who is barely ill from it.”

By Easter, Jason had been under sedation and on a ventilator for nine days, and on ECMO for nearly that long. That weekend doctors decided to try the convalescent plasma, as well as the experimental drug they’d considered earlier.

While Michelle worried, doctors began to see signs of hope he might survive. Then, the day after Easter, his condition suddenly began to improve. His chest x-ray and his lab results got better every day.

“He just rocketed forwards,” she says. A few days later, providers were able to turn off the ECMO, and then the next day the ventilator.

On April 16, hospital staff disconnected all the tubing.

Little by little, Jason started to wake up. He had no idea how he got there, drifting in and out of awareness. A collage of family pictures, put together by a friend, hung from the wall of his hospital room. It said “You Are Loved.”

“Sometime during my recovery phase in the ICU, I must've seen this collage. So in my dreams, I went through multiple different scenarios of me on my deathbed,” Jason says. “It was very much just time to reflect on what's special in life.”

He remembers the moment when he started to realize what he’d been through. He didn’t recognize the person at his bedside, a doctor he’d never met before at least when he was awake.

Jason says it was a confusing celebration.

“It was basically high fives, like, ‘Oh my gosh, you made it. It's so great to see you. Fantastic. You beat this thing,’” he said.

That doctor at his bedside was Joe Forrester, a pulmonologist. He says it’s common for patients who’ve been under so long and had their sleep cycle disrupted to be disoriented when they wake up. Jason had been unconscious for nearly two weeks, with no understanding of what he’d been through.

Jason remembers telling Forrester “Oh, okay, yeah, I'll get through this. This is a journey. We'll power through it.” He says Forrester said something like, “No, no, you don't understand. You made it through the tough part. You made it. It's so great to see you.”

Forrester says he told Jason he’d “already done all the hard work and he will make it home. And I think before that he really didn't see an end in sight.”

“Man, I was, I was more on that side than this side. I beat the odds,” Jason said. “I was completely overwhelmed.”

Jason had lost between 25 and 30 pounds in two and a half weeks. He couldn’t unlock his smartphone at first because the facial recognition software didn’t recognize him.

Back when Jason got sick, Michelle had circled one key date: her birthday on April 18. She’d prayed Jason would be awake by then and told friends the only thing she wanted was for him to be healthy enough to celebrate the day.

“It started getting closer and closer and I was like, ‘Oh my goodness.’ You know, I honestly didn't feel like we would be reaching this point,” she said.

On April 18th, two days after he woke up, Jason wished her happy birthday over Facetime. “It was the best thing I have ever heard,” Michelle said.

Their daughter Kestin says everyone, including family, friends and neighbors, pitched in to help the family while her dad was sick.

“It's amazing. There were so many people supporting him,” she said. “That gave me a lot of confidence that he was gonna make it.”

Jason’s illness and recovery offered valuable insights for his medical team on why people survive.

The ECMO certainly kept him alive and he was part of an FDA clinical trial using convalescent plasma. In Colorado, nearly 1,000 people have been treated with that therapy. No publication time frame for the drug trial results has yet been announced.

Researchers are also studying tocilizumab, which Jason received, though not as part of an FDA clinical trial. The drug has been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, and is among a number of other treatments to deal with the cytokine storm Jason experienced.

Still, none of his doctors are sure of what saved him.

“I don't think any of us know, or we'd be treating all COVID patients with a certain therapy regimen,” Hanna says.

But it seems likely his fitness was a decisive factor. Forrester says that didn’t stop Jason from catching COVID-19, but it helped him muster the strength to fight it off. He had to overcome the stress of being on a mechanical ventilator, ECMO, and lying in bed for weeks, which can lead to muscle atrophy.

“Having someone who's fit — that makes a tremendous difference as to whether they'll survive that kind of insult,” Forrester says.

“Needless to say, I did not think this (COVID-19) would impact me, if at all, minimally,” Jason says.

Cooper believes the fact that he was hospitalized and then on ECMO relatively early in his illness “probably had the most impact,” a testament to Michelle’s early push to get Jason to the hospital.

Forrester said Jason recovered so thoroughly he didn’t have any visible residual lung disease and wasn’t on oxygen anymore — a rarity for COVID-19 patients.

“It's just a matter of rehabilitating his arms and legs and he should be back to normal as if in a year this never happened,” he said. He showed a remarkable ability to heal and “to reverse such extensive lung injury to the point where it's almost negligible.”

Many COVID-19 patients who get released from the hospital will face ongoing health problems. Those lucky enough to survive may suffer permanent disability, including things like kidney failure, neurologic damage and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Like other COVID-19 patients, Jason survived due to an array of modern medical marvels and dozens of highly trained medical professionals.

That kind of care doesn’t come cheap.

An analysis from California projected for COVID-19 patients that the average hospital stay of 12 days would result in a $72,000 bill. Since most are older, Medicare would cover most of those bills.

But ECMO amplifies the costs, according to a Kaiser Health News report last year.

“ECMO is very expensive, mostly due to the labor involved: A person on ECMO cannot live outside the ICU and must be continuously monitored for complications, such as blood clots, bleeding, infection and loss of blood to the limbs,” KHN found.

Median charges for ECMO in 2014 were more than $500,000, making it among the top 15 most costly procedures, according to federal data.

Jason’s care included nearly three weeks in the hospital, plus lengthy spans on a ventilator as well as ECMO. The Jahanians still aren’t sure how much that will cost them.

“I haven't seen any bills yet. I mean, I've heard estimates of over a hundred thousand dollars a day in support,” Jahanian said. He expects to start getting bills soon, but says he has good insurance through his company. He is watching to see if there will be some government assistance to help coronavirus patients pay their medical bills.

But for Jason and Michelle, questions of cost are secondary at this point.

“I'd rather not pay 60 grand,” Jason said. “Quite honestly, being alive, I don't care. I'll pay whatever.”

They’re lucky. It’s still unclear exactly whether insurance carriers and government health insurance programs will fully pay for treatment of COVID-19 patients. Both have vowed they will, but insurance industry experts and health care economists expect to see surprise bills and gaps in coverage.

The day finally came when Jason was healthy enough to go home.

Melton, who treated him as he recovered, told him a few members of his medical team wanted to say goodbye. He got in a wheelchair and she took him to the elevator. When they got downstairs and rounded the corner, they met an explosion of cheers.

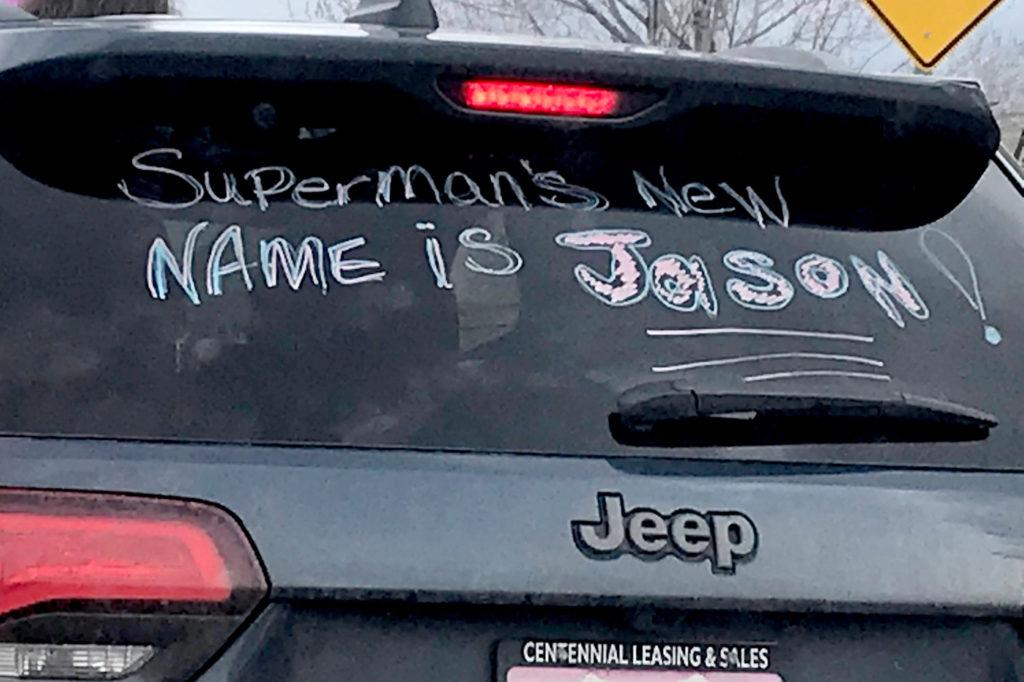

The moment was caught on video, the kind that has trickled out in the last few months, moments of joy in a dark time. Jason was one of the first survivors to leave The Medical Center of Aurora; his video was one of the first to go viral. It shows Jason in a green t-shirt with “Best Dad Ever” written in huge white letters. A nurse hands him several balloons. Dozens and dozens of hospital staff, most wearing blue scrubs, wave and cheer. One carries a sign that reads “Survivor!!!”

At first, Jason looks stunned. You can’t see his face behind his mask, but you can see his eyes. He’s crying and blowing kisses and patting his chest with his arm, as if to say thanks from my heart.

“It was just absolutely breathtaking,” says Melton. “I was a large ball of tears, but I mean it was incredible. It was an amazing feeling to be filled with happy tears.”

“That's so rare for us to send someone home home after being that ill,” says Cooper, one of the first people to greet him after he woke up.

Dr. Jennifer Hanna, who treated Jason for the worst part of his illness, wasn’t on duty the day he was released. She watched the video on Facebook, sitting in bed with her husband and kid.

“I was in tears watching him,” she said. “It makes us feel like we're doing this for a reason.”

Hanna said at that point, the hospital was seeing probably one or two deaths every day from COVID-19.

“The staff really needs to see a win every now and then,” she said.

Still, she worries that the worst isn’t over yet, that Jason may prove one of the lucky ones.

“With things starting to open back up again, I'm not sure that really the curve has flattened the way people think it has,” she said. “I worry a little bit that we're maybe jumping the gun, and we're gonna see another spike as things start opening back up.”

On April 21, the day Jason was released, 36 people died, one of the deadliest days in Colorado so far. Since then, hundreds more have died, although fewer each week.

Public health leaders and medical providers are warning of the potential for a bigger second wave of coronavirus cases. In recent weeks, the state has gradually reopened businesses and seen protests against racism and police brutality. Both have brought together larger gatherings of people, potential venues for spreading the virus. Scientists tracking the pandemic have sounded the alarm that cases could surge again if people don’t continue social distancing at high levels.

"The virus is still here, and it could surge back the moment we let our guard down," Gov. Jared Polis warned earlier in June.

The Jahanian family isn’t thinking as much about that right now. Instead, they’re thinking about the moment at the hospital, when COVID-19 released Jason from its clutches. He got in the car with Michelle and they drove away.

“It was awesome, awesome to see him alive, breathing,” she said. “(It was) the first time that I was able to touch him in like 18 days, it was the best thing ever. I don't know how to explain it.”

It takes about 20 minutes to get from the hospital to Lone Tree and Jason wanted the windows rolled down, to feel the wind in his hair and the sun on his face for the first time since getting sick. Winter had finally ended while he was in the hospital, and everything was turning green.

“That drive home was so, so real,” Michelle says. “He was just taking it all in.”

Jason says he’ll remember the lessons of this time: Appreciate life, appreciate the little things, appreciate your family.

“I'm a very appreciative guy in general, but this just compounded this thing a hundredfold,” he says. “Life has a whole new meaning, walking outside has a whole new meaning, rolling down the window has a new meaning.”