Raverro Stinnett’s injured brain processes thoughts in ways that can resemble the abstract art he once made. His thoughts sometimes blur into one another or just fade away, like the nebulous faces he used to paint.

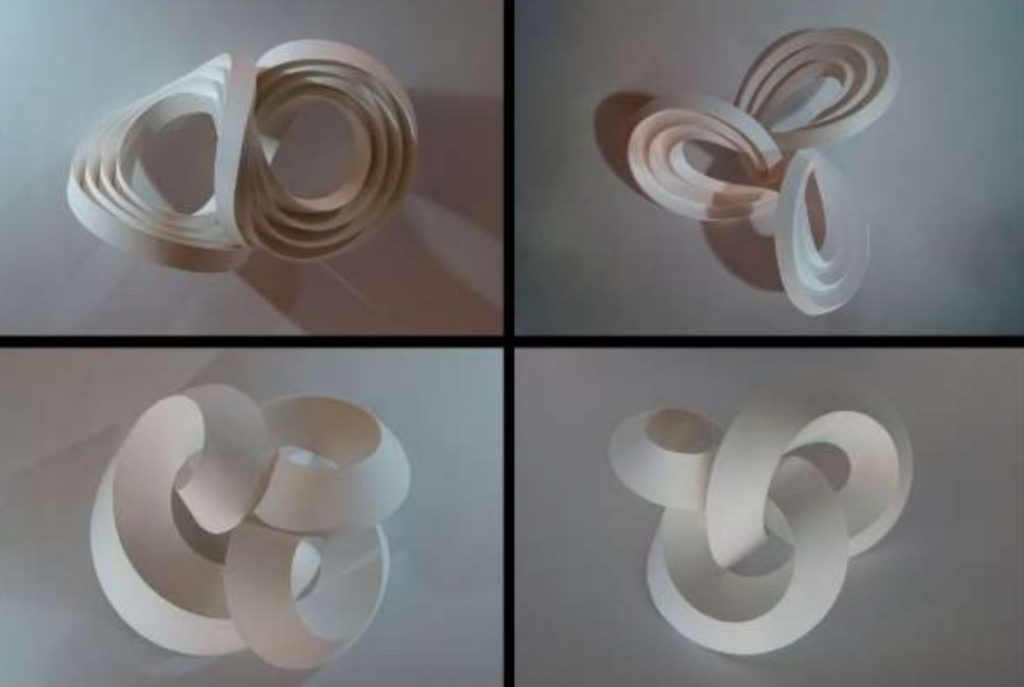

His 3-D sculptures of paper knots undulate with no apparent beginning or end, like an infinite ivory churro or pretzel, metaphors for how his brain-damaged mind now functions.

Stinnett’s artistry, raw yet bursting with talent, had caught the attention of prominent Colorado artists and benefactors. A rising star within Colorado’s burgeoning Black art scene, he was studying at Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design on a full scholarship and was in line to become an artist in residence at RedLine Contemporary Art Center, one of Denver’s premier art incubators and galleries.

But early on the morning of April 20, 2018, Stinnett’s art career came to an abrupt halt.

Shortly after leaving a party at RedLine art center on Arapahoe Street to catch a train home at Union Station, a security guard working there assaulted him. He was beaten so severely that he suffered permanent brain damage.

The effects linger more than two years later. His speech veers from halting to rushed, sometimes in the same sentence. His eyes have difficulty focusing. He’s forgetful, shy to ask a question to be repeated. And, most frustrating for him, making art brings on anger and pain, not the exciting bursts of expression it once did.

“There's things that I stay away from because it leads back to emotion,'' Stinnett told CPR’s Colorado Matters in his first radio interview since he was attacked. “It seems like every time I try to paint, I just bust out in tears. Or if I'm even making the sketch for the painting, it's just tears. It's all tears.”

'You can go wait in the bathroom where there's no cameras'

He said he was listening to music when someone approached him.

“They were security guards,” he recalled. “I didn't hear what they're saying or anything, but I took out my headphones, and they was like, ‘Hey, what are you doing?’ And I was like, ‘I'm just waiting for the train.’ And they was like, ‘Well, you can't wait here.’”

“Then it turned into, ‘Where am I going to go?’”

Stinnett said one of the guards told him, “You can go wait in the bathroom where there's no cameras.”

“I just wanted to end the conversation,” Stinnett said. “If that's where I got to wait, then that's where I got to wait, basically. So I walked to the bathroom.”

The last thing Stinnett remembers happening in the underground bus facility bathroom is James Hunter putting on a metal-studded glove just moments before he unleashed a sucker punch to Stinnett’s head.

“He must've hit me hard because I got a scar here,” he said, pointing to his right eye. “A scar on my nose. All of this was busted up. My teeth were jacked.”

“He didn't just hit me one time and then I have all this damage,” he added. “He had to have hit me more than once, I'm thinking. My face was swollen.”

Hunter worked for Allied Universal Security. The Regional Transportation District, which manages bus and train service in the Denver metro, subcontracts the company to provide security at Union Station. Hunter and three other Allied security guards participated in Stinnett’s attack. Hunter did the punching, and the others stood watch outside the bathroom.

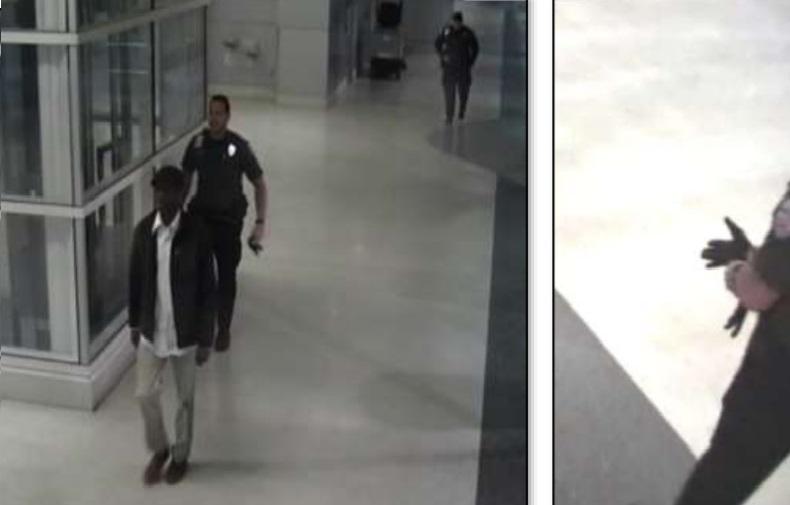

Stinnett’s memory of Hunter attacking him only came weeks later. After the attack ended, Hunter and the other Allied personnel left Stinnett in the bathroom. Security camera footage shows him leaving the bathroom bleeding from his head.

Dual investigations and a long road to recovery

Stinnett made his way home to Montbello in northeast Denver but has no recollection how. He said he must have boarded a train, then caught a bus because he had no money for a taxi and no cell phone to call friends.

In severe pain and incoherent, Stinnett slept for 36 hours. Friends began to worry when they could not contact him.

At the time, Stinnett could not remember any details of the assault. He told a friend someone must have jumped him. A few days later, the friend posted about the attack on social media.

The post caught the attention of Union Station and RTD and an internal investigation was launched. Allied essentially investigated itself. One of the guards involved was in charge of gathering information from the other participants, who all gave similar statements denying any role in Stinnett’s beating.

Then the Denver Police Department began an investigation of its own.

Soon it became clear to Denver police that Stinnett’s attackers were Allied security personnel, not a random assailant.

Hunter confessed to beating Stinnett in an interrogation with prosecutors from the Denver District Attorney’s Office. He told them he cleared the bathroom of everyone except Stinnett.

“I told them to leave,” Hunter said on the tapes, “because Mr. Stinnett and I were going to fight in the bathroom.”

In his criminal case, Hunter pleaded guilty to felony menacing and received a prison sentence for attacking Stinnett. Two Allied security guards, officer Victor Diaz and Sgt. Taylor Taggart, received probation for their part standing watch and not halting the attack or coming to Stinnett’s aid. A fourth Allied guard, officer Aaron Fougere, cooperated in the investigation and was not charged.

RTD issued a statement to CPR News condemning the actions of the Allied security guards. It says in part:

“RTD is sensitive to the concerns our society has regarding policing. The Stinnett case was an isolated event of criminal activity that does not align with RTD’s core values nor does it reflect our attitude, mission, policies or practices. As horrible as this incident was, this is about individuals’ bad behavior, and those individuals are suffering the consequences.”

Stinnett has filed a civil lawsuit against RTD, Allied and the four guards involved. He said they are responsible for a culture and actions that led to his “permanent cognitive impairment and behavioral changes.”

Discrimination and violence in 'Denver's living room'

Qusair Mohamedbhai represents Stinnett in his civil case. Mohamedbhai, who sat in with Stinnett while he spoke with Colorado Matters, said Stinnett’s assailants targeted him for being Black.

“It was just premeditated violence and racial profiling,” he said. “There was no reason at all for them to even have spoken to Raverro, to approach him. He was doing nothing other than waiting for a train. He was just a Black man in a public space that they didn't want him there.”

Mohamedbhai said Allied’s employees’ actions echo a pattern of police brutality against people of color.

“This is the government, through its agents, inflicting substantial injuries upon the community. This is transit security, safeguarding government property,” he said. “This is no different than what a law enforcement officer or a department of corrections guard might face.”

Stinnett was blunter. He said he was attacked because the color of his skin stood out, not because he was doing anything unlawful.

“There's no doubt in my mind. There were others waiting around. No one else had to leave,” he said. “There was even a person sleeping right across the bench from me, and they didn't say anything until that person woke up and carried on.”

Union Station markets itself as “Denver's Living Room, a space for locals and visitors alike.” Stinnett said that hospitality was not extended to him.

The RTD statement does not specifically address racial profiling. Instead, it touts protocols for how security personnel interacts with homeless people and those with mental health issues, none of which pertained to Stinnett at the time he was assaulted.

“We continue to explore options that further enhance our approach to address situations involving people experiencing homelessness and mental health issues while still providing security,” RTD’s statement continues. “Additionally, we are working with community members on the agency’s Code of Conduct to ensure it strikes the right balance in requiring appropriate behavior on RTD’s system while respecting people’s rights.”

Stinnett’s lawsuit contends he will never regain the level of artistry he once had. It pains him to accept this reality, but he’ll keep trying to make art because that’s what his tight-knit community wants from him.

“I have friends that push me,” he said. “Will I be as fast or as good or as precise? It's something I have to work toward, but it's not as easy. I'm just much slower at doing things. Or I have to think about things more than once or twice in order to get it right.”

Editor's Note: This story was updated to clarify the location of the bathroom where the attack took place.