On July 8, a group of local county public health directors from around the state got on their regular conference call.

The percentage of positive coronavirus tests was rising across Colorado, as were hospitalizations. The trends threatened the limited freedoms counties had gained in recent weeks from state health restrictions.

The discussion turned to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, the most important partner for the counties in the pandemic response. Following recent departures at CDPHE, they were trying to figure out who their point of contact is now, four months after the first COVID-19 case was discovered in Colorado.

“I don’t know who to go to,” said Tom Gonzales, public health director for Larimer County.

“I think we need to see an org chart when they figure it all out,” said Liane Jollon, the executive director of San Juan Basin Public Health in Durango. To underscore the importance of figuring that out, she added, “Our jobs are completely, inextricably linked to state health.”

County public health agencies depend on CDPHE’s more than 1,400 employees and $600-plus million budget for everything from expertise and guidance to testing kits and facemasks.

And CDPHE is a department in transition, right in the midst of the biggest public health crisis to hit the nation in more than 100 years. The agency has lost at least 12 high-level leaders in disease and disaster response and the county liaisons who provided a crucial link between the state and locals. Six of them have left since COVID-19 hit Colorado.

The counties have felt it. They are the single most important partner the state has in responding to the pandemic, especially since many feel that the federal government has abdicated its leadership role.

Colorado is a strong local control state and the counties are responsible for investigating outbreaks. But the 53 county public health agencies also look to the state for guidance — and political cover — when making unpopular decisions like shutting down businesses or requiring masks.

With a background in local public health management and consulting, Jill Hunsaker Ryan, the executive director of the CDPHE, would seem well-positioned to have a mutually beneficial relationship with Colorado’s county health officials as they wrestle together with an unprecedented crisis.

That has not always been the case.

CPR News reviewed hundreds of pages of emails and text messages, along with hours of recordings of phone calls between local public health directors, finding a fraught relationship, with regular complaints about a lack of communication and guidance from the state. The problems have stretched throughout the pandemic, despite assurances from CDPHE and the governor’s office that the relationship was improving.

Public health leaders say a fully-functioning state public health department is critical, because of the failure of leadership at the federal level.

“The problem we have had with this pandemic,” said Mark Johnson, executive director of Jefferson County Public Health, in an interview, “is that when we have turned to the state we've had a lack of good communication and leadership. And when the state turned to the feds, the feds said … ‘You're on your own.’ So the whole system that had been built up over decades really fell apart right away.”

Johnson’s concerns were echoed by others at the county level, especially in regards to communication with the state.

“There is no doubt that it has been a challenge,” said Jeff Zayak, executive director for Boulder County Public Health in an interview with CPR News.

Ryan has acknowledged some rocky moments in relations with the counties during the pandemic but said she has never forgotten how important they are to the overall state response.

“Local county public health agencies are our greatest partners. We operate as one system,” said Ryan in a July 2 interview. “And we've heard from local public health that they have wanted to be more involved and provide input into policymaking. I meet with the local public health directors weekly. Our state epidemiologist meets with county epidemiologists twice a week. And in fact, local public health directors were very much involved in framing the new ‘Protect our Neighbors’ framework.”

Gov. Jared Polis’ office declined multiple requests to make Polis available for an interview. In a response to written questions, spokesman Conor Cahill said: “In a disaster there is often not enough time for stakeholder engagement, it’s the unique burden and responsibility during a statewide emergency for the governor to make quick decisions to save lives — this was especially the case in the early days of the pandemic.”

But Cahill said that things were getting better.

“As this emergency has progressed into a multi-month effort to sustain the progress made in suppressing the virus we have been able to do more stakeholder engagement on policy formation with our local partners,” Cahill wrote. “But as we are very much still in an emergency this is not always possible.”

As an example of how out of the loop counties are, Johnson, the Jefferson County Public Health director, didn’t know Karin McGowan, the deputy executive director of CDPHE, had left the agency until CPR News told him. (Ryan sent an email to the public health directors later that afternoon.)

“That, again, is concerning,” said Johnson.

McGowan was at CDPHE for more than a decade and was viewed by many as a critical piece of continuity.

She was appointed by Polis to a new full-time post as a commissioner of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission.

McGowan declined to comment. Local public health directors feel her loss.

“You are a tremendous asset to public health in this situation,” Theresa Anselmo, the head of the Colorado Association of Local Public Health Organizations wrote McGowan on May 1. “CALPHO members and I so greatly appreciate you.”

Gunnison Public Health Director Joni Reynolds, who recently appeared at a press conference alongside Ryan, said she has been pleased with the state’s response.

“The level of engagement I've seen at the [CDPHE] executive level has been stellar,” said Reynolds. “And I expect that translates throughout the organization. I've seen a lot of people step in and step up in this response, both at the state level and at the local level.”

But when asked who her official point of contact with CDPHE was, Reynolds said: “Typically it had been Deborah Monaghan and Karin McGowan.” Both have left CDPHE in recent weeks. Reynolds said she didn’t realize that McGowan had left CDPHE when CPR News interviewed her on the morning of June 22.

In light of that, she agreed that it wasn’t clear who the point of contact is.

Monaghan was the interim director of CDPHE’s Office of Planning, Partnerships and Improvement. Monaghan declined to comment. The OPPI office is the main conduit for county public health directors to interact with CDPHE. It once housed four full-time positions. Now there are none.

Monaghan took over for Anne-Marie Braga, who left her leadership role in the office last fall. Braga, a 14-year veteran of the department, was beloved by many county public health directors. Braga didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

In June, Monaghan took a position with the state Department of Human Services. After Monaghan first announced she was leaving in late May, Shannon Kolman at CALPHO emailed her, writing, “I’m glad you have a lifeboat off that ‘sinking ship’ …” She later told CPR News she was referring to the loss of people within CDPHE’s office dealing with the counties, not the department generally.

‘It makes us look really foolish’

County public health directors have taken a lot of heat through the course of the pandemic. Some have received death threats. Some must regularly spar with county commissioners pushing to reopen a battered economy. And some have been fired for standing up for public health principles.

The burden of their jobs is made harder by a fractured relationship with state leaders.

An example of that came on June 2, when Polis announced an initiative that, on its face, seemed like good news for overworked county public health agencies: The state would recruit 800 Americorps and Senior Corps volunteers to conduct contact tracing — the detective work of tracking down people who may have been exposed to the virus before they can infect others.

But the next day on a conference call, local public health directors vented about the governor’s surprise announcement.

“It makes us look really foolish,” said an exasperated Anselmo.

The public health directors had a slew of questions no one had answers to: What skills do these volunteers have? Who would train and manage them? How long would they be employed as tracers before moving on?

And the timing of the contact tracer news couldn’t have been worse for some public health directors, who were in the process of asking the counties they serve for millions of dollars to do the work the state now said it would take on. The state’s announcement of 800 contact tracers undercut them.

“It’s ludicrous,” said Dr. John Douglas, who leads Tri-County Public Health, the state’s largest local public health department, on the Zoom conference call. “I don’t know whether (state Coronavirus Innovation Response Team Lead) Sarah [Tuneberg’s] got too many things on her plate, but I think we need to say, ‘Look this is a teachable moment. Please don’t do this again. This is incredibly counterproductive to confidence building and trust enhancement.’”

Counties have struggled to figure out what Tuneberg’s role is exactly.

Ryan said Tuneberg is the “testing and containment czar.” She was hired by the state to replace email entrepreneur Matt Blumberg as head of the Innovation Response Team on March 22 — the same day she interviewed. “Talk about a rapid recruiting process!” wrote Blumberg, in his blog.

Tuneberg was referred by Brad Feld, Polis’ friend, who also referred Blumberg, according to Blumberg’s blog. Feld did not respond to a request for comment.

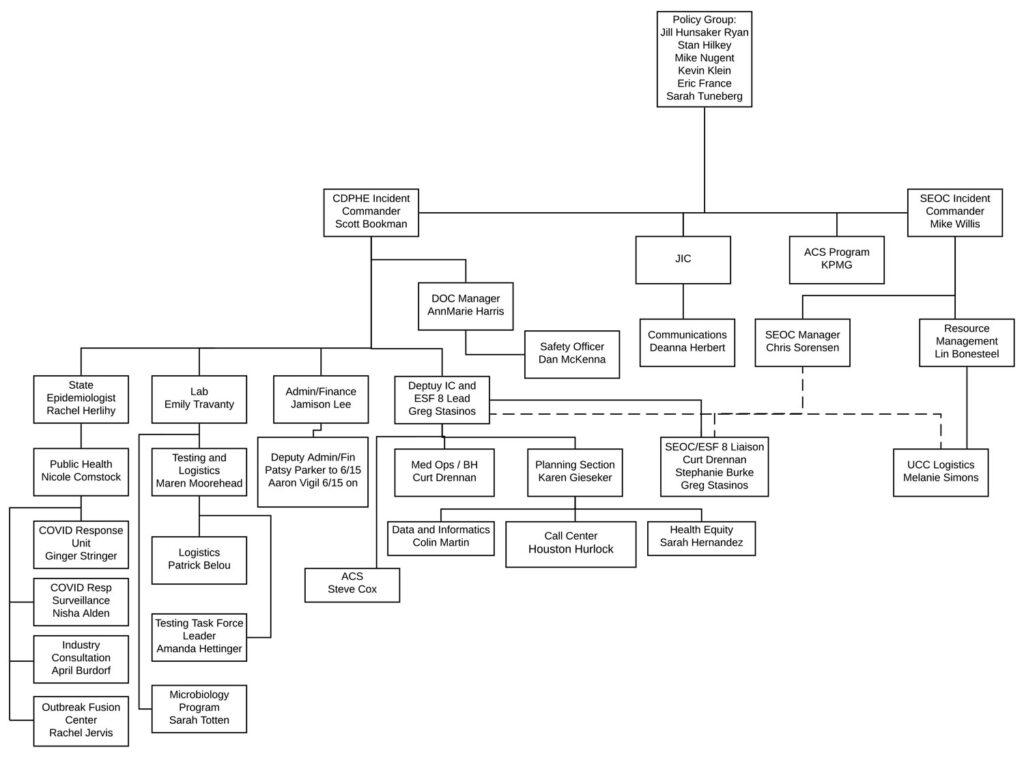

She is listed at the top of the state’s COVID-19 response organizational chart, with Ryan; Ryan’s deputy Mike Nugent; Eric France, the CDPHE Chief Medical Officer; Stan Hilkey, director of the Department of Public Safety; and Kevin Kline, director of the Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

Tuneberg has a master's in public health and worked in tech and consulting before coming to the state. She runs several companies, including Geospiza, which helps companies navigate climate change. Her bio says she has “15-years of emergency management experience as a leading national expert in vulnerability.”

CDPHE did not make Tuneberg available for an interview with CPR News. But she sent a statement through the department in response to written questions.

“The opportunity to secure Americorps service members came quickly, and it was a powerful opportunity that I didn’t want to pass us by. This innovative solution allowed the state to quickly scale up contact tracking and save the state more than $25 million,” Tuneberg wrote. “Still, I always welcome feedback, and it was a teachable moment. I am always striving to communicate effectively and in a way that keeps pace with this rapidly changing pandemic.”

In an interview, Douglas said his frustrations with the state, generally, stem in large part from failures by the federal government.

“I would give what the state's done so much better a grade than what I've seen the feds do,” Douglas said. “And I think the state just got left on its own to kind of figure it out, whether it's a testing strategy, which is just abysmal the way the feds have handled it, or PPE procurement, once again, abysmal the way the feds have handled it.”

The state was “working with at least one hand tied behind their back because there were things they were expecting to happen that in any rational federal administration should have happened,” Douglas said.

But every state has been dealing with the same federal government. Almost all have managed to test a higher rate of their residents.

In interviews and emails obtained by CPR News, the recurring theme is that the state is making local public health — their most important partner in fighting COVID-19 in Colorado — look “foolish.”

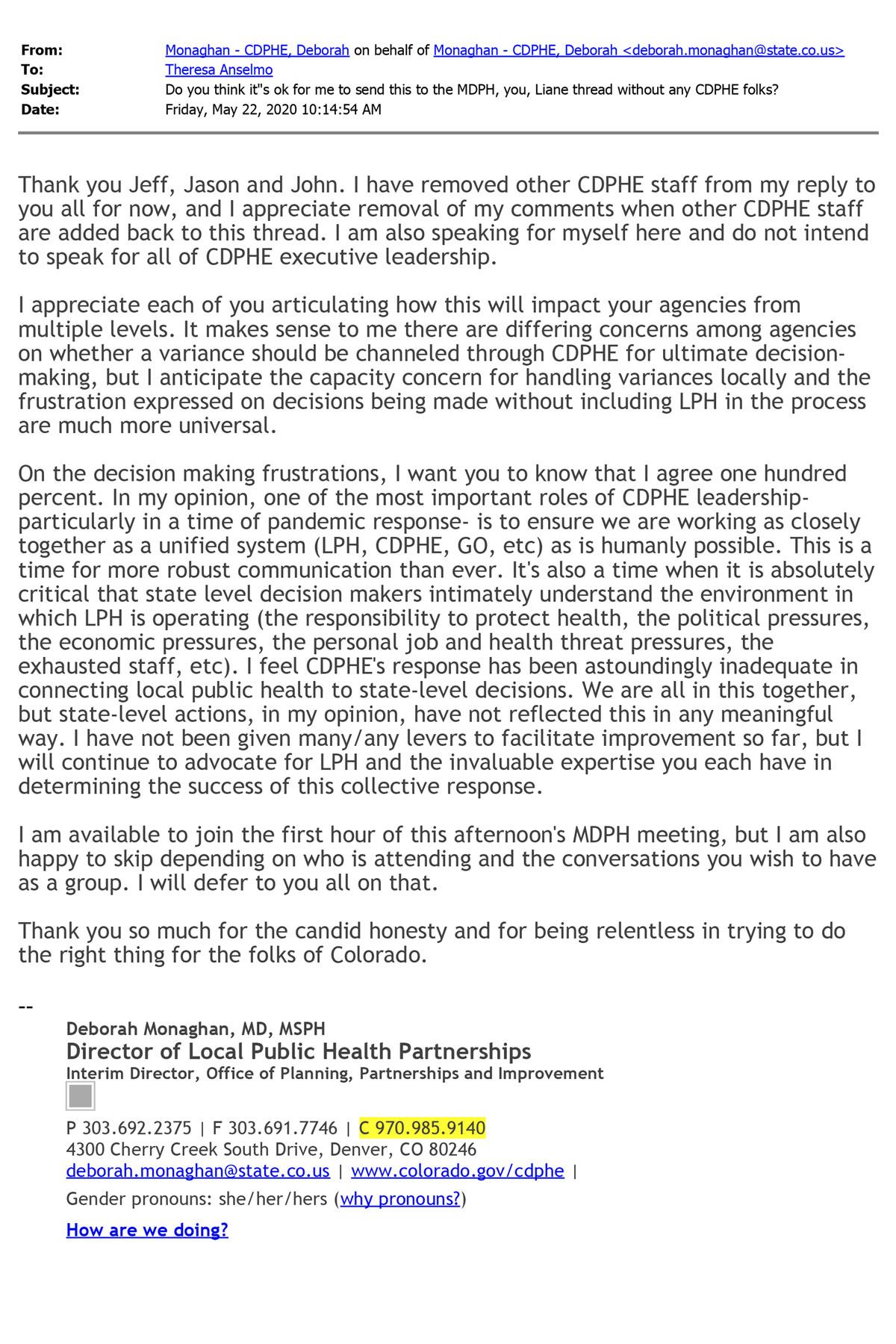

For instance, in an email to Monaghan on May 22, Jason Vahling, Broomfield’s public health director, wrote about his concerns with the variance process, where counties can be released from some state health restrictions. Vahling wrote he learned that the process would be left to local public health through his mayor. “But it makes me look foolish because I have no idea these ideas are being considered by CDPHE or the Gov.”

“This process highlights the dysfunction in our public health governance and structure,” he added.

Monaghan, with the state, wrote back an hour later, but not to defend her then-employer: “I feel CDPHE's response has been astoundingly inadequate in connecting local public health to state-level decisions. We are all in this together, but state-level actions, in my opinion, have not reflected this in any meaningful way.”

“I am also speaking for myself here and do not intend to speak for all of CDPHE executive leadership,” wrote Monaghan.

Ryan, CDPHE’s executive director, has a background in local public health, but it did nothing to strengthen that bond between locals and the state.

Ryan is neither a doctor nor a regulatory lawyer, so Polis’ selection of her was a change from the resumes of the men and women who were chosen by the last three governors to run the state’s sprawling public health department. As the head of Eagle County’s public health, according to her Linkedin page, she oversaw 19 people and a budget of $2.4 million.

But she was on the committee in Polis’s transition team responsible for finding a new CDPHE head. It turned out to be her.

Ryan holds a master’s degree in public health from the University of Northern Colorado, and she wasn’t a total stranger to CDPHE before taking over the top spot. She held various roles in the department over seven years, including heading the Office of Health Disparities for two years. She spent three years as a consultant, helping develop the Colorado Health Assessment and Planning System for CDPHE.

The governor’s office defended Ryan’s credentials to run CDPHE — and her performance.

“Jill Ryan is not only eminently qualified, she is uniquely qualified to run CDPHE and its dual mission of protecting the public health and the environment,” Polis spokesman Cahill wrote. “She’s done trailblazing work that led to the creation of the health equity office at CDPHE. Then as a two-term county commissioner in the congressional district the governor represented, the governor worked with Ryan on climate change efforts for years.”

At the time of her state Senate confirmation in 2019, no senators focused on the jump she would be making to manage an organization as large as CDPHE, or how she might guide the state through the kind of pandemic that has been anticipated nationally for years. As the nominee to head the state agency charged with protecting public health, along with air and water quality, she was instead mostly questioned on climate change and the environment, including the state’s promotion of electric cars.

Roots of county unhappiness start in March

Just after midnight on March 18, an email from the head of Kaiser Permanente was forwarded to the governor.

“The increase in CO positive cases of COVID-19 over the last few days in the setting of very restricted testing (due to severe swab shortages and limited testing availability) along with increased persons with ‘influenza-like illness,’ signals that Colorado likely has community spread of Coronavirus,” wrote Mike Ramseier, president, Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Colorado.

The email was written to Polis’ Chief of Staff Lisa Kauffmann, on March 17, who forwarded it to the governor about 10 hours later.

“Strong consideration for Coloradoans to shelter in place x 6 weeks,” advised Ramseier.

The pressure to issue a stay-at-home order was mounting on Polis without a lot of epidemiological talent left at CDPHE to advise him.

Two days earlier, on March 16, Polis met with the Governor's Expert Emergency Epidemic Response Committee. There was debate about stay-at-home orders. Polis didn’t indicate what his intention was for a statewide order, according to Mark Johnson, Jefferson County’s public health director, who was there. CDPHE said there are no recordings or minutes from the meeting.

“At that time we really got no particular read from the governor that he was going to move [on a statewide stay-at-home order],” said Johnson.

Other metro county public health directors kept making requests through CDPHE for the state to do something. They weren’t getting much response. “So we, at the local level, at least here in the Denver region, put together an order, ” said Johnson.

“We were trying to get things ready, trying to move forward and felt at that time all of the models said every day that you wait is thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths.”

Six days after the GEEERC meeting, on March 22, a Sunday, Polis called a press conference announcing, not a stay-at-home order, but an order requiring employers to reduce in-person workforce by at least 50 percent.

He also emphasized that he’d be “entrepreneurial” in his approach to the response and scaling up testing, especially since states felt abandoned by the federal government as supplies became scarce.

“Governors will continue to play an unprecedented role in our response,” said Polis. “We are rising to the occasion. We are bringing in the expertise. We need to scale our response and leverage our relationship with elected leaders across the state, as well as private industry partners.”

And he said the “grim reaper” would be the ultimate motivator for social distance.

For its part, Kaiser Permanente wasn’t done trying to push the governor to take additional steps.

An email the afternoon of the March 22 press conference, from Ramseier, included modeling done by Kaiser, and a note: “While data points in any of the models we all have undoubtedly seen thus far can be disputed, they all point to the same general conclusion. We must be proactive and the best defense against community spread will be at the policy level.”

The next day, Denver Mayor Michael Hancock announced a stay-at-home order for the city starting Tuesday, March 24, and other large counties followed suit. On the morning of March 25, Jefferson County and Tri-County announced their orders.

Later, on March 25, Polis announced his own statewide stay-at-home order going into effect two hours before Jefferson County's order on Thursday, March 26. It came more than a week after metro counties first pushed for a stay-at-home order.

“So he sort of stepped in and took over the leadership of it in a way that was a bit troubling to us, because he didn't communicate with us,” said Johnson. “We had already announced what we were going to do. And he, he really undercut it, sort of in almost a showboating manner, took over.”

Some within CDPHE have begun privately referring to the governor as “Dr. Polis,” for his tendency to offer medical advice and quote statistics during press briefings where he is only occasionally accompanied by medical professionals.

But public health experts also give him credit for being among the nation’s first governors to wear a mask himself and emphasize widespread mask usage among residents as a means to control the spread of the virus.

In a pattern that recently mimicked his deliberate pace with the stay-at-home order — what one public health director called “Groundhog’s Day” — Polis issued a statewide mask mandate, after several counties and cities had issued their own, and only after regular intervention from counties asking for help against a resurgence of the virus.

Masks have become a political flashpoint in the U.S. and in Colorado, despite clear evidence of their effectiveness.

Without a statewide order, a local patchwork of mask mandates developed. Local public health directors, who serve at the pleasure of county commissioners, took heat as they instituted local orders requiring masks.

But for some county public health directors, a statewide order is the only hope of getting a mask order in place in their communities.

So the local public health directors decided on July 8 to draft a series of letters to the governor and Ryan making the case for a statewide mask order.

“Relationships for Public Health Directors across the state are frayed,” reads the July 10 letter. “Some directors have been fired and many have been threatened and harassed. This should be a statewide order, and not an order left up to multiple jurisdictions to try to accomplish, many of whom will not due to politics.”

Six days later Polis agreed.

“I want to thank our local leaders for leading the way.”

Read deeper into CPR News' investigations into Colorado's response to the coronavirus pandemic: Read part 1 of this story on turnover and the state's difficult start to testing or read the untold story of how the government reacted behind the scenes as the coronavirus crashed into Colorado.