Updated: 11:33 a.m.

As classrooms start to reopen their doors to students in the face of the pandemic, coronavirus isn’t the only thing that has some Greeley parents worried. Their children will go back to a school that’s less than two city blocks away from an active oil and gas pad.

“I’m scared, I don’t know what to do. My kid has to go to school. I was happy that my kid could be home,” one mother said.

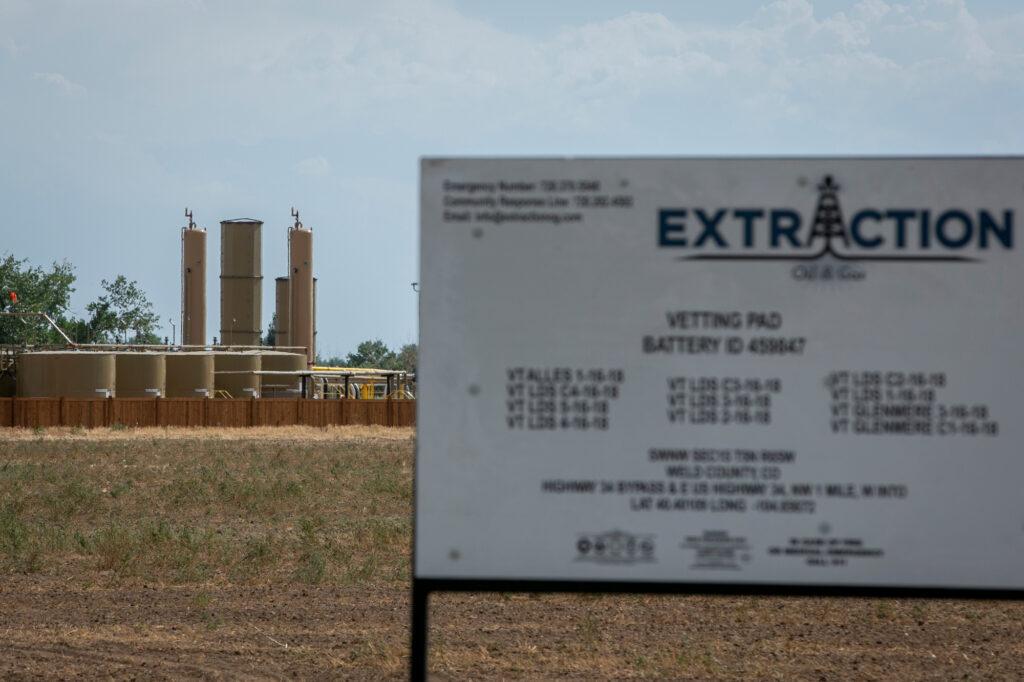

Her son goes to Bella Romero Academy 4-8 on the far east side of Greeley in Weld County, in one of the top oil and gas producing counties in the country. Small homes and open fields of farmland surround the campus, where Denver-based Extraction Oil and Gas’ tanks stand taller than the few trees on the landscape about 1,200 feet from the school’s playground.

A few weeks after the wells first started to flow in October 2019, a state mobile lab stationed at the campus detected an elevated level of benzene. The chemical, odorless and invisible, hung in the air as the final bell rang and kids ran out to meet parents and board buses.

“Every day we stand and wait in that big, long line to pick up our kids. We could have got affected by it too,” said the mother, whose son is in the eighth-grade.

CPR News spoke with parents and staff anonymously so they could share their concerns without fear of retribution and verified the identities of these sources. A majority of Bella Romero students are Latinx, and some are part of refugee, undocumented or mixed-status families in a community where many work in the oil and gas industry.

Nearly three weeks passed before the state detailed what happened: On Nov. 5, 2019, the mobile lab measured a benzene level of 14.72 parts per billion, which exceeded the federal short-term health impacts guideline of 9 parts per billion. Many parents first learned about the incident through local news coverage. The school didn’t know about the benzene spike until just before a press release was shared.

The original press release reported a lower benzene level of 10.24 parts per billion due to a data processing error. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment published a statement on their website in April 2020 to explain the error and does not believe it changes their initial assessment that anyone was harmed in the incident. The state said the benzene exposure was lower than the level known to cause headaches, skin and eye irritation and respiratory issues.

“I was pretty upset. I’m still upset. I feel like the whole thing is getting sugarcoated,” said the mother. Her husband used to work in oil and gas but quit because he felt it was too dangerous.

The state determined the benzene likely came from an oil and gas operation, but their investigation couldn’t make a conclusion as to its exact source. While Extraction’s site is the closest active well to the school, there are 115 facilities within 3 miles that have emissions permits. There are nearly 20,000 active wells in Weld County.

Extraction Oil and Gas is adamant that they were not the source.

“We set about inwardly scouring our facility, our data, our logs of what kind of operations were being conducted there, who was working on the site and what was happening,” said Brian Cain, a spokesperson for Extraction. “Based on all of the puzzle pieces that we put together and based on the reams of data that we were able to get from our facility to analyze, we are confident in saying we don’t believe that this came from our facility.”

But without a definitive answer as to what caused the benzene spike, parents and staff of Bella Romero are left with their concerns and a still-pumping site right next to the school. They’re worried more toxic chemicals could be in the air and that leaks will go unknown or unresolved. They don’t trust that their kids are safe.

Shut down the wells

For Patricia Nelson, the incident on Nov. 5 was her “worst nightmare being realized.”

“This is exactly what we’re afraid of,” Nelson said. “That the children were going to be exposed to carcinogens.”

Nelson’s 7-year-old son, Diego, goes to Bella Romero Academy K-3, about a mile down the road from the 4-8 campus. Nelson wants the wells shut down before he gets to the middle school.

She recently submitted a petition to Gov. Jared Polis, which demands that he do just that. Nelson said she collected about 40 signatures in person from parents, grandparents and siblings as they waited to pick up kids. She said it was an encouraging moment since it’s been a challenge to get others to speak out publicly, even though she’s heard from parents privately about their concerns.

“This work I do is exhausting. It’s draining and it’s scary,” Nelson said. “To have other parents tell me to keep going and to thank me for what I’m doing, definitely makes it worth it.”

The coronavirus pandemic shifted her efforts to collecting signatures online, which led to 1,000 more before she sent it to Polis.

This isn’t Nelson’s first attempt at trying to stop the operation. She’s been the public face of this fight since the state first approved Extraction’s permit to drill 24 wells behind the school in 2017.

She learned about the plan at a community meeting.

“I remember just being so shocked,” Nelson said.

It was there that she was approached by members of Weld Air and Water. They told Nelson that they needed a parent to join a lawsuit against the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission.

“I was just so mad, I was like, ‘I’ll be the parent,’” Nelson said. “Completely not knowing what I was getting myself into. Because in my mind, this was going to be open and shut. Like, nobody in their right mind would put an industrial site next to a school.”

The lawsuit, brought by environmental groups and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Colorado chapter, claimed that allowing Extraction to drill near Bella Romero was unfair treatment. The plaintiffs called the operation an “egregious example of environmental injustice.” The development has drawn protests, arrests and national attention.

The wells were originally planned to be drilled near Frontier Academy, a mostly white school just a few miles away from Bella Romero. That plan was scrapped in 2014 after angry parents pushed back. Mineral Resources Inc., which Extraction acquired in 2014, said in a statement at the time that withdrawing their application was an “example of listening to community concerns.”

The new drilling site became the one near Bella Romero, where the majority of students are Latinx and 85 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, compared to 19 percent at mostly-white Frontier Academy.

“It’s this stark disparity that raises concerns of environmental justice at Bella Romero,” the lawsuit stated. “The [Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission] and operators generally experience the least amount of pushback when siting major oil and gas development in predominantly minority communities since these communities do not have the same resources as more affluent communities.”

In an email, Cain said the location was ideal for Extraction because it let them use pipelines instead of trucks to haul away what the well produces, which reduces the impact on air quality. The site also allowed for an electric-powered rig and production facilities, “which the other pads did not,” Cain said.

The lawsuit’s first day in court was the same day another Extraction site east of Windsor caught fire after an explosion in December 2017. Judges in both district and appeals courts ruled against it.

Why don’t you just move away?

For Nelson, the fight has been lonely. She’s the only Bella Romero parent who’s consistently spoken out against Extraction Oil and Gas publicly — a stark contrast to the opposition the operation faced from the white and more affluent parents at Frontier Academy.

“I know a lot of these families aren’t as privileged as I am, despite being a woman of color in the United States. I am an American citizen,” Nelson said. “So I can speak my mind without being afraid of repercussions.”

Nelson also acknowledges that many of these families rely on the industry for work and that there’s strong support for oil and gas development in the community generally. People have asked Nelson why she doesn’t move her son to another school if she doesn’t like what’s happened.

“I can do that, but my sister can’t,” Nelson said. “How many other parents out there don’t have the ability to move their kids to another school? This is my home, and one of the biggest philosophies we have at the school is that we are a family. So I’m going to do whatever I can to protect my family.”

“If I quit there’s not going to be anybody else,” Nelson said.

Speaking out

CPR News interviewed a Bella Romero staff member and parents who signed Nelson’s petition to shut down the wells. As with the parents, the staff member spoke on the condition of anonymity because she feared retribution.

The staff member said she was “shocked and disappointed” when she learned that the wells would be drilled.

“It seems like such an injustice that this is happening to this population,” she said. “It’s so unfair that they’re having another thing thrown on top of all their adversities that they’ve faced in life, like here’s another health impact.”

She’s concerned about her own exposure to the operation too. She’d like to one day have children, and she’s worried about working close to oil and gas wells while she’s pregnant. Studies, including one from Columbia University, have found associations between pregnant women living near oil and gas development and adverse birth outcomes.

A state health study found people who live within 2,000 feet of an oil and gas operation could be exposed to emissions at concentrations high enough to cause short-term health impacts like nosebleeds and headaches. Oil and gas groups have spoken out against the study’s methods, which uses modeling for its findings with data collected several years ago.

Lynn Granger, executive director of the Colorado Petroleum Council, said in a statement last fall that “Using modeled exposures instead of measured air quality data introduces uncertainties and limitations that may result in erroneous estimates of risk for a population.”

Other research out of the Colorado School of Public Health finds that people who live within 500 feet of a well in the state may experience a lifetime excess cancer risk eight times higher than the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s upper acceptable levels.

“When I do become pregnant, I’m going to have to advocate to the principal for me to avoid the 4-8 campus,” she said. “I wouldn’t be comfortable if I’m still employed three or four years down the line.”

Monitoring the site

Extraction Oil and Gas filed for bankruptcy protection in June because of a coronavirus-driven oil and gas bust. The Bella Romero staffer is afraid the company will abandon the site, which could make the situation worse. Cain said all operations are normal and that they do not anticipate any interruptions.

Last fall when the elevated benzene level was detected, the state was monitoring air quality at Bella Romero in response to concerns about the wells. Without that data, the school and parents would have never known about the benzene incident. The Bella Romero staffer is worried that something worse will happen — or maybe already has.

The mobile lab recorded 1,500 hours of air quality data at the school for 88 days, between the months of May and December of 2019. The equipment detected just the one benzene spike over the federal short-term health impacts guideline of 9 parts per billion.

For half of that time, the lab was measuring air quality before the wells started flowing. The baseline data shows that levels of benzene and other chemicals were generally higher in the days after the wells started production in October 2019.

“I think our data, not just from this site, but from other places we’ve monitored shows higher levels of volatile organic compounds during oil and gas development,” said state toxicologist Kristy Richardson. “We saw that at the school as well. I think what we didn’t see was a level at which we would be concerned for public health.”

The staffer and parents who spoke to CPR would like to see more consistent air monitoring at Bella Romero. The state recognizes that’s a challenge since the technology is expensive — it only has one mobile lab to move around to different oil and gas sites, and the equipment was removed from the 4-8 campus in December 2019. It was replaced with a system that can detect volatile organic compounds in the air, and canister samples can be sent to a lab for a breakdown of contents and quantities. The state plans to get the more sophisticated mobile lab back to the school before classes resume in August.

To bolster monitoring abilities, the state’s Air Quality Control Commission will consider a new rule in September that would require air quality monitoring at oil and gas pre-production development sites. Polis also recently signed SB 204 into law, which provides the state with more resources for advanced leak detection technology, including aerial surveys and satellite imagery.

A lack of information breeds fear

Regardless of where it came from, the November 2019 spike in benzene has some parents more concerned about the operation than they were before. The mother of the eighth-grader wants more transparency and a promise that the development is safe.

“I feel like they don’t care about the safety of the children,” she said. “If they cared, the well would never have gone up and education would have been the priority.”

Another mother echoed the feeling that she’s being kept in the dark.

“We don’t know much of what the school is doing to protect the children and make sure that they’re safe,” she said. “It’s alarming and scary to know that we as parents barely know what’s going on, do they know what’s going on? Like what to do in case something does happen?”

The Bella Romero staff member said she isn’t aware of any specific emergency plan in place at the school if there was an incident at the wells. In a statement, Greeley-Evans District 6 superintendent Deirdre Pilch said the school’s security chief has put together an “enhanced evacuation plan,” and said that plan has been communicated to staff members.

The state released a health consultation in June that suggests Extraction Oil and Gas develop a plan as well, and “communicate with the school and residents in the event of an emergency that could expose people to harmful levels of air pollutants.”

Cain said they do have an emergency plan that they’ve shared with the local emergency district, and that operations will automatically shut down if an emissions threshold is met.

The health report also suggests that the district monitor 4-8 students for health issues like headaches, nausea and nosebleeds, so that the school can work with the state to assess any trends. The mother of two Bella Romero students would like to see the school send out more information, to “keep us updated on what we should be looking out for.”

“We’ve never had to deal with these issues. Like COVID-19, it’s all new to us,” she said. “It’s like, you guys need to educate us on these issues and let us know what’s going on and what to do.”

The mother said that when she talked with her daughters about the benzene incident, they told her that teachers and school administrators never talk about the wells.

“They feel like they can’t bring up the subject,” she said. “So that kind of scares me that the children don’t even know what’s going on.”

A gas leak detected

Nelson, the other parents and the Bella Romero staffer have reasons to doubt that they’re getting accurate information from Extraction and the school.

The company told Bella Romero administration and parents in 2018 that they would complete pre-production steps, like drilling and hydraulic fracturing, when kids were out for the summer.

Research, including the state’s human health risk assessment for oil and gas operations in Colorado, has found that flowback has higher emission rates of some volatile organic compounds, including benzene, than other phases of oil and gas development. The flowback phase is when the water, chemicals and sand that were pumped into newly drilled wells returns to the surface, along with oil and gas.

Extraction reiterated it would complete flowback “before school starts,” in fall 2019, as written to school administration in a June 28, 2019, email, which was shared with CPR News. The school then sent out a note to parents at the start of the 2019 fall semester, that read “All major operations have been completed on the wells, including drilling and flowback activities … There are no plans for additional drilling or flowback activity on the site.”

This didn’t end up being the case.

The wells were hydraulically fractured in June 2019, but the mixture of water, chemicals and sand stayed in the ground until mid-October. That’s when Extraction opened the wells and started a hybrid phase of simultaneous flowback and oil and gas production.

The company adopted updated flowback technology for its site to reduce emissions. Cain said that this newer technology blurs the lines, so “our industry really had difficulty at that time precisely saying when flowback ended and production started… For our primary purposes, which are to always ensure healthy air quality and safe operations, there was no difference.”

The state agrees that the system should be cleaner than older ways of dealing with flowback.

“That’s assuming everything was designed correctly, this is still kind of a new approach,” said John Putnam, director of environmental programs for the state health department. He said the mobile air monitoring is part of learning more about what emissions systems like these could release.

It’s still unclear why Extraction didn’t explain this to the school, which left both administration and parents unaware of what was actually happening at the well pad. In response to the question, Cain pointed back to the technology and said, “We essentially eliminated the typical flowback phase.”

While the technology might be advanced, it can still malfunction. CPR News has learned that a gas leak was detected in Extraction’s equipment at the same time as the benzene spike. The leak in a pipe joint was discovered on Nov. 4, 2019, the day before the elevated benzene reading. Extraction fixed the leak in the days after.

Extraction concluded the leak was too small to be the source of the benzene.

“For context, the [state] gives an operator five days to repair leaks of that size because of their minimal impact on air quality,” Cain said.

The state agreed with their assessment based on what they were told about the leak in question.

This doesn’t sit well with Patricia Nelson, who learned this information through CPR News.

“To know that there was a gas leak, and they didn’t evacuate our kids?” she said. “I have no words, this is just cruel at this point.”

Nelson believes Extraction should be required to share specific information of any gas leak, no matter how big or small, with the school and parents. She’d like to know how many other leaks have been detected at the site, but that’s information she won’t likely get. Companies aren’t required to report on individual leaks, just a summary of how many leaks were detected and fixed within a year. In 2018, Extraction reported more than 3,000 leaks in its operations across Colorado.

For their part, the state wants to strengthen their leak detection but said it’s not realistic to report the details of each and every one. In 2018, they identified nearly 24,000 leaks.

In response to Nelson’s calls and petition for Extraction’s operation to be shut down, a spokesperson for Polis released a statement that said, “Protecting the air we breathe is a top priority for the Governor, especially for those Coloradans disproportionately impacted by air pollution... CDPHE will continue to perform air monitoring and take steps to improve air quality to ensure the protection of the health and safety of students at Bella Romero school.”

The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission said that with the passage of SB-181 in 2019, which makes health and safety higher priorities when considering oil and gas regulation, it likely wouldn’t have approved Extraction’s permits to drill behind Bella Romero if it was a question today.

But that doesn’t change the reality for Nelson and her son Diego.

“He asked me if something happens, are we going to be OK? And I can’t answer that. Nobody can answer that, and nobody wants to answer that,” she said.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to clarify that CPR News verified the identities of the anonymous sources.