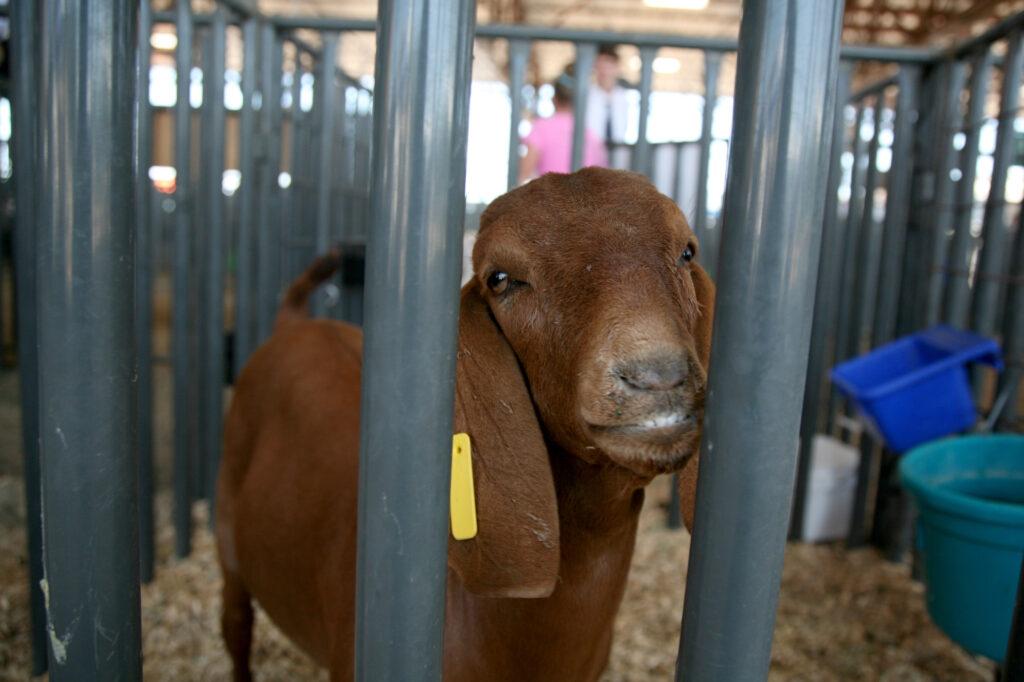

The sheep and goats, pigs and cows that lounged in the shade of the covered, outdoor arena had no idea about the strange times we live in now. They didn’t know it was a Mesa County Fair like none before it — or that the coronavirus has forced fairs to contort and constrict all across the country.

Something about hanging around their pens, more spaced-out than normal, felt like an invitation to forget about things for a little while. The earnest young handlers helped with that, too.

Bright-eyed Jentri McFarland smiled as she showed off her “big boy,” a black steer named Spirit. It would be the first time the 9-year-old showed him, or any animal, at the fair.

“I’m totally pumped!” she said, also admitting she might get some stage fright. But she was sure her steer, chomping on hay behind her, would remain calm. “Spirit’s a good boy. He’s always there for me when I need him.”

Colorado’s Agriculture Commissioner deems livestock shows and sales essential, which is why the animal component of fairs all across the state can continue, where it’s safe enough — fairs need the permission of local health departments. Mesa’s was contingent on COVID-19 levels that remained relatively low.

That’s a big deal, said Melissa Wonnenberg, who heads Mesa County’s 4H program, as kids use proceeds from their livestock to buy next year’s animals — and sometimes to save for college.

Without this year’s shows and sales, “it would have been a huge hole in an already tough year,” she said.

Counties harder-hit by the coronavirus, like neighboring Garfield, have had to move all their contests online. But in Mesa, even without the fair’s normal carnival rides, funnel cake stands — or even the public — in-person livestock shows means she can feel the fair’s familiar atmosphere.

“A lot of that is still there, even though there's a lot more empty space than there is normally,” Wonnenberg said with a light chuckle.

That space comes from physical distancing measures and the fact that at least a quarter fewer families are participating in this uncertain year.

The children who were there said they were glad to be showing off their animals, even though 12-year-old Danielle Long admitted it was also kind of sad.

“Yeah, because I get super attached to them,” she said as she stroked Rocco, her white-and-black lamb. With school out the last few months, they’d spent a lot more time together and “just became really close friends,” said Long, wearing earrings with little lambs painted on them.

Like most 4-H animals, Rocco was destined to soon be auctioned off.

“It's going to be really hard when he leaves,” she said. “But I’ll get over it when I get my next lamb.”

For some 4H kids, however, this year was the end of the line. In a cavernous barn filled with cattle and giant fans to keep them cool, 18-year-old Antonio Treto Alvarez cleaned out the hooves of his final 4-H steer.

“He does not have a name, but I think we can just call him ‘Ted,’” Treto joked. “Improv!”

He added that Ted was one of the nicest steers he’d ever had, and he thought the big guy would go far in his competition. It would be a good end to Treto’s 11 years, which started with lambs.

“I’ve probably raised more sheep than math assignments I’ve turned in,” he quipped.

Treto just graduated high school and plans to work for a while before heading to college. Standing next to Ted’s stall, he was surrounded by that earthy, pungent smell of manure. He smiled as he called it “homey.”

“It’s kind of comforting, which is a weird thing for most people to hear,” he said, explaining that it smelled like the fair always does.“There’s people out and about. They’re taking care of their animals. They’re getting stuff done. It’s a nice feeling, and it’s a nice smell.”

It was a whiff of something normal, in a time so alien.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to clarify that livestock events also need the permission of local health authorities.