Five-going-on-6-year-old Gabriel Burbage looked straight into my eyes when I asked him if and how he wants to go back to school.

“I want my teachers back,” he said. “I feel like coronavirus is not cool for me. School is fun for me. I feel like it’s a lot funner than going to online school because you just get to do a lot of e-du ... e-du-cation and you get to learn more stuff.”

In that, he speaks for a lot of kids. Brianna Meza, a 15-year-old in Jefferson County, can’t believe she’s saying it, but she really misses school. Being away from it for several months has been “really rough.”

“I am a social butterfly. I love talking to people. I love being in school activities.”

Still, she chose to go back with 100 percent virtual learning, because she thinks it's the healthiest option and wants to help flatten the curve once and for all.

Young people are experts when it comes to school. Many have years of direct, recent experience. Each child, young and old, has been through a lot since school doors closed because of the novel coronavirus.

Yet they’ve been largely left out of back-to-school planning and discussions, rarely asked: how they feel about returning to school, what remote learning in the spring was like for them, and how it could be better.

CPR News spoke with students across the state about what they’re thinking with the school year looming.

One Colorado survey of more than 1,000 students shows only 4 percent were asked for input before the switch to remote learning last spring. Two-thirds gave online learning low marks. Forty-four percent of students did not have access to one or more resources they needed to fully complete their schoolwork after the shift to online learning.

There was a bright spot: More than two-thirds noticed some level of reduction in bullying and a third witnessed no bullying.

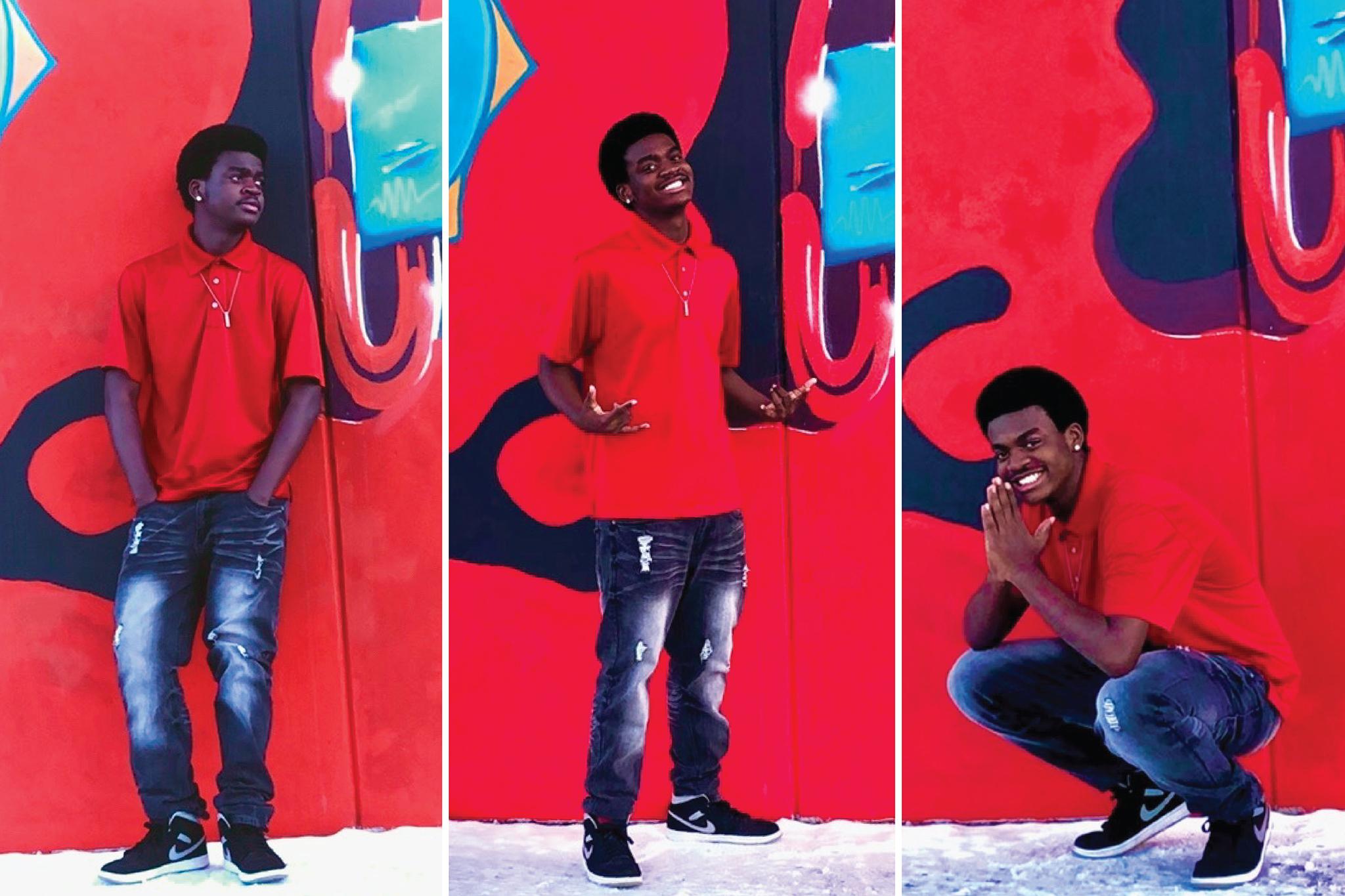

Caleb Washington, a 17-year-old who attends school in Aurora and classes at the Community College of Denver, said basic things like internet bandwidth and annoying younger siblings make remote learning hard for him.

Aurora schools will be doing remote instruction for the first quarter, so Caleb will soon sequester in his bedroom for at least a couple of more months of learning remotely.

Caleb has to share bandwidth with two of his siblings who are also taking classes online. In the spring it worked like this: He’d make a schedule for himself, around when his siblings would be taking classes, and wait until they were done to hop online. It may be trickier this fall as districts plan much more synchronous learning, where kids have to be online at the same time as the teacher.

- Colorado School Districts Say They’re Ready To Roll. But Surveys Show Widespread Anxiety Among Teachers About Reopening

- How Will Denver Public Schools Handle Equity In Online School, And Four Other Back-To-School Questions

- High School Football And Other Sports Cement Spring 2021 Seasons As Colorado Coronavirus Cases Fall

- What Teachers And Parents Are Saying Ahead Of Colorado Schools Reopening

- What Is Cohorting? And Is It The Cure For Colorado’s Coronavirus School Worries?

- Colorado Gears Up For Online Learning With Digital Access Push — And One Victory for Undocumented Families

Caleb also has two younger siblings, not yet in school, and just as he was explaining this to me, one of them barged into his room.

“I’m on a phone call,” he told the child.

“My room doesn’t have a lock so they just constantly just barge in,” he said, laughing.

The interruptions distracted him a lot last spring.

Caleb said he’s a hands-on learner. Learning remotely was harder for him.

“I like to have access to my teacher,” he said. “So if I need an answer to a question, you know, they can (help).”

But Caleb said it's safer learning at home now — and he is a teenager.

“I don’t have to wake up super early to get to the bus stop and all this extra stuff,” he said.

He thinks school administrators need to think long and hard about the impact of virtual learning has on kids. For many kids he knows, school was an outlet for them to get away from their homes.

“So for them to be stuck in that, I know it has been detrimental,” he said.

Like other teens, Caleb is trying to balance school work, his mental health, and making money to help support the family when his dad lost his job. His biggest advice to teachers is to designate an “open vent time” for kids to talk about their experiences during the quarantine.

“I know for a lot of people talking about our problems helps us work through them,” he said. “I understand that school is ... for learning, but also school is a big, important part of our life. Like, we spend eight hours a day going to school for five days a week. So just having a ton of time for a space to just talk about, ‘Are you OK? And like, how can you support (us) and actually follow through and show up?”

Other kids had an easier time with remote learning. Tammy Le said she didn’t feel the enormous pressure she normally feels at school. She is shy so being at home was a lot less stressful.

“In school, there was always this pressure to talk to people,” Le said. “So even like having to ask the teacher a question, I don’t like it. For me personally it’s easier to do it over a screen.”

She called remote learning “laid back and relaxed,” but stresses that it wasn’t that way for all kids. School was just so busy all the time. Being at home has allowed her to connect more with herself, she said.

“I’ve picked up painting," she said. "I’ve always loved painting but I never had time to do it because I never had time in school.”

But she misses her friends. Her high school will start remotely but then is offering a choice: all virtual learning or hybrid model, a mix of in-person and remote. She chose the hybrid model that features alternating days of in-person and remote. But then — she changed her mind. She said the school’s health plans seem vague.

“They haven’t explained to us 100 percent, like, it’s not clear what they want to do,” she said.

She’ll be taking classes online this fall.

Brianna, a theater kid, said choosing to learn remotely was a tough choice. She’s outgoing and laughs a lot. She desperately wants to go back to school and found the online workload in the spring learning immense. But talking it over with her parents, 100 percent remote was the best choice for her, “to keep us all safe and finally flatten the curve and get over it.”

She’s skeptical teens will physically distance during in-person classes.

“I'm very like, around my friends, grabbing their backpacks to follow them in the hallways, because I'm short and they're super tall. They can walk away faster than I can," she said. "Or, everyone's like constantly like on each other, like hugging, you've got like high schoolers running around all over the place, giving each other piggyback rides.”

But she knows being away from high school has been very rough on some of her friends, who’ve fallen into a depression.

“I know a lot of my friends are going through very dark times right now where they feel hopeless,” she said.

The Colorado youth poll showed more than 70 percent of students feel that social distancing has negatively affected their mental health.

“It's just rough,” Brianna said. “Not being able to have a fun teenage life at the age of 15 because no one's really willing to do what they're supposed to. I feel like if everyone had worn a mask or maybe socially distanced a bit more than maybe me and my pals could be prancing on the stage and screaming our heads off.”

Middle schooler Eric Petersen of Durango doesn’t mince words when it comes to what he thought about remote learning.

“Online learning stank,” he said. “I hated it so much. Just sitting at a screen all day, not even a real person, just a tube ... even though screens aren’t made out of Cathode-ray tubes anymore, it's really unnerving if you sit there too long, your eyes start to unfocus and you literally can't do anything.”

“I like human interaction,” he said.

He thinks about kids who might not have an internet connection or devices at home to be able to see friends, even through a screen.

“I could see this time being a lot worse, even leading to depression because it's near impossible to see your friends safely if it's not on a screen,” he said.

Even though he really wants to get back to school, he thinks for the health of everyone, remote is the best option. His family hasn’t decided what model of learning to choose. One thing Eric knows is that he’s ready for summer to end.

“They’re only so many times you can reread Harry Potter before it gets really annoying,” he said.

On the other hand, incoming seventh-grader Julia Ragan of Denver feels going back to school in-person is safe if you take precautions.

“I appreciate that people are trying their best to fit everybody's needs and everything, but I don't really feel a whole bunch of risk with it. I’m just 12,” she said.

Adults make up most of the known COVID-19 cases to date. But positive tests in children began rising sharply in late July. Children are far less likely to be hospitalized as a result of COVID-19 according to a recent study, but Black and Hispanic children are more likely to experience symptoms requiring hospitalization than white children.

She didn’t really like long blocks of online classes, she misses movement, she misses individual conversations with people that don’t happen even in Zoom breakout rooms where the teacher chooses your partners.

“When you're in class, sometimes you can choose the people you are going to work with,” she said. “It was a part of talking with other people individually that I really appreciate, where you can't really get it with strictly online.”

Tucker Blue, a 12-year-old from Englewood, likes online learning a bit more than in-person but wasn’t satisfied with his classes last spring. “It was a little bit boring like sometimes I would just take the computer and just walk around the house because it was just so tiring to sit around and do nothing.”

His district is offering hybrid learning for older students. But he finds that confusing.

“I don’t get the point of going in some times and not the other times,” he said. “I think it should just be one or the other. I get that you can’t really be in school all the time but it’s a bit weird to have it be one and then the other.”

It’s really the young kids who seem the most desperate to get back to school in-person.

At a homegrown neighborhood summer camp in Denver, a posse of kids of all ages crowded around me to tell me they were not thrilled about more remote learning.

“You don’t have friends to play with,” said one.

Sometimes it’s something as simple as the monkey bars.

“We always do the monkey bars after school,” 9-year-old Knox said. “We have this special place you can do pull-ups and we see who we can do more and it’s just kind of boring when you can’t do that.”

To them, it just feels like school is where learning is supposed to happen.

“I don’t feel like I can focus a lot when it’s on the computer,” said 10-year-old Zadie.

“Home, it’s like a hangout place for me — and also, I want to go back to school ‘cause I’m going to a new school and we have to do it online and that’s going to be hard for me,” said Knox’s brother Noble, who will be starting middle school.

For students who haven’t ever been to school, this fall offers a particular challenge. Maya, who is five, starts kindergarten soon. I asked her if she was excited, and her voice got high and anxious.

“Not really, because every time I go to school my first time, I’m kind of scared!” she said.

This fall, she won’t be alone in that feeling.