A family in the San Luis Valley has made an X in masking tape on the kitchen counter. It’s the only place a remote hotspot works so the children can access remote school lessons.

A mother who runs a hair salon in Commerce City brings her daughter to work with her. It’s the only place she can access online learning using her mother’s hotspot. But it means the mother has problems running credit cards at the same time.

A third of students in the South Routt School district south of Steamboat Springs don’t have internet access.

Teachers, parents and school superintendents told these stories during the Internet Access Summit Wednesday calling for affordable and universal internet, faster download and upload speeds and higher data caps, and training to ensure families can access quality connections.

The virtual summit, sponsored by Coloradans for the Common Good, a coalition of education, labor and faith-based groups, included teachers, school officials, elected officials, and representatives of internet service providers Comcast, Verizon and T-Mobile.

“It’s frustrating,” said Toby Melster, superintendent of the Centennial School District in San Luis, Colorado. He estimates about 30 percent of his students are falling behind simply because they don’t have a high-quality internet connection. He said companies have donated some hotspots but because there are multiple people in a family who need to go online, “they’ve got to make a decision about who gets access to the hotspot.”

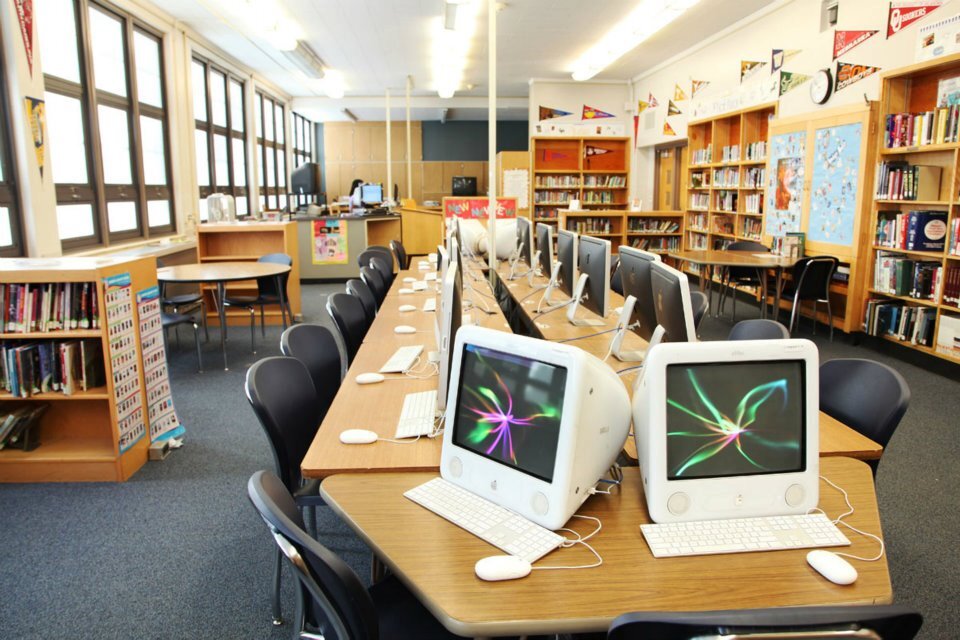

The shift to remote learning exposed a deep digital divide between Colorado students.

That could exacerbate existing educational inequities. Although 90 percent of city and suburban districts have high levels of broadband connectivity, only a quarter of the 112 rural districts in Colorado have high levels of connectivity, and many have low or very low levels, according to an analysis by the Regional Educational Laboratory Central at Centennial-based Marzano Research.

Students with broadband internet are defined as having internet speeds greater than 25 Mbps, or “megabits per second.” That’s a measure of internet bandwidth or the speed at which a person can download data.

For example, 94 percent of the 28,200 students within Mesa County Valley School district have broadband internet. But across the state on the far eastern plains, only 18 percent of the 61 students in the Plainview School District have broadband.

It’s not just a rural problem. Low-income neighborhoods such as Denver’s Montbello and Green Valley Ranch have spotty coverage and many students are trying to use their phones as hotspots.

Zuton Lucero-Mills of Green Valley Ranch has seven people in her family accessing the internet for grade school and college.

“I was on an online call a week ago and the wind blew my internet went out,” she said.

School districts have invested in devices to try and close some of the technological gaps. Denver spent millions of dollars to purchase 2,700 hotspots and more than 40,000 Chromebooks. But an estimated 4 percent of district families don’t have the high-quality connection that allows families with working parents and multiple children to have remote access.

“Piecemeal solutions to educate students virtually will not be enough without expanded broadband access,” said Denver Superintendent Susana Cordova. “This is about the essential work of teaching and learning that now requires significantly more investment in high-speed broadband.”

She called on Colorado’s U.S. senators to include funding for connectivity in the next recovery package and for more support from businesses.

The federal government has spent billions of dollars to expand access to outlying areas.

Senator Dominic Moreno says the state government’s role is largely through grants that come from a 2.6 percent assessment on telecommunication providers. Legislation has directed the money to bringing high-speed broadband to rural areas.

“But that leaves out a critical component: What about low-income families in urban areas?” Moreno said.

Some areas outside major metros such as the Steamboat Springs area in Routt County have used grants to form public-private partnerships between schools, hospitals, and cities to install costly fiber-optic networks.

- Refugees And Families Of Color Press Aurora Schools To Improve Their Whole Remote Learning Approach

- What Colorado’s First Day Of School Looked Like In A Pandemic

- What Do Kids Miss About In-Person Learning? Play, Their Teachers And Real Learning

- What Is Cohorting? And Is It The Cure For Colorado’s Coronavirus School Worries?

Tim Miles, technology director in the Steamboat Springs school district, sees power in working together. He and the technology directors at two school cooperative associations formed the Colorado Education Broadband Coalition, which connects 50 schools.

“We’ve saved enormous amounts of money for those schools because we go to bid as one big large school.” He hopes to expand the coalition to the entire state.

Still, families in outlying areas may not benefit.Ciara Bartholomew, the business and finance manager for the South Routt School District said the district has patched together some short-term solutions. The district collaborated with organizations to put up cell phone towers, which “hopscotch” to another tower to provide connectivity to students. It invested in a router device placed in a school bus that’s parked in high-need locations.

“It is not the long-term goal,” she said. “The long-term goal really needs to be laying a fiber in the ground and making sure this is a utility like water and like a roof over a student’s head.”

Telecommunication companies will have to be part of the fix, too.

At the summit, representatives from the telecommunications companies Verizon, Comcast and T-Mobile outlined efforts they’re making so far to expand access.

Comcast has worked closely with several Colorado school districts to connect more families to its low-cost Internet Essentials package. Verizon says it’s lifted and increased the data caps on mobile phone users. T-Mobile says it had designed a program to help solve the “homework gap” for students who couldn’t complete assignments online from home. He said the company is in the process as it merges with Sprint of redesigning that program for full-time learning.

“How do you create universal access? It takes all of us,” T-Mobile’s Brent Cooper said, referring to the fact that different companies have different coverage areas. “I think all of us working together, we can help make a big difference.”

The three companies committed Wednesday to working with the Coloradans for the Common Good on a plan to selectively boost coverage in certain areas.

Cooper cautioned that while the intent to expand coverage is good, there has to be buy-in from municipalities.

“Sometimes we're limited by a city that’s saying you can’t put up a cell site there. The reality is, we need to put up a really big cell site in order to cover a big area but then we get limited to, ‘You can only put it on this building or it can only be this tall, you just can’t cover as many people with good wireless coverage.”

Denverites will vote on a measure this November to exempt the city from a state law that prevents local governments from investing in broadband services and infrastructure. It could pave the path one day for citywide high-speed internet.

“We do not impede some families’ access to our libraries and we should not impede some families' access to the internet,” Denver councilman Paul Kashmann said during the virtual summit.

Teachers and school officials say they can’t wait much longer.

Kevin Vick with the Colorado Education Association said teachers are trying to design high-quality, engaging lessons, but if kids can’t connect, they tune out.

“They’re not going to even try to turn the machine on or even engage and that’s where we are losing lots of students,” he said. “This isn’t going to go away just because COVID may be dissipating.”