Beethoven’s “love of man” was the essence of his being. But his pain and frustration, largely due to his loss of hearing, caused him to seem misanthropic at best; cruel and unfeeling at worst. His music, though, showed his commitment to universal brotherhood, especially in his only opera, “Fidelio.”

Beethoven 1802, Heiligenstadt, ViennaDivine One, thou lookest into my inmost soul, thou knowest it, thou knowest that love of man and desire to do good live therein.

Washington National Opera’s production of "Fidelio" for Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, originally scheduled for the fall, has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when the opera is eventually performed WNO artistic director Francesca Zambello will revive some ideas from her 2003 production.

“'Fidelio' speaks so much to the people, not the aristocracy, and that was [the concept] Beethoven was addressing at that time,” said Zambello. “The whole notion of free speech, the enlightenment, the rights of man — and I'm sure if he were alive now he would say — the rights of all people.”

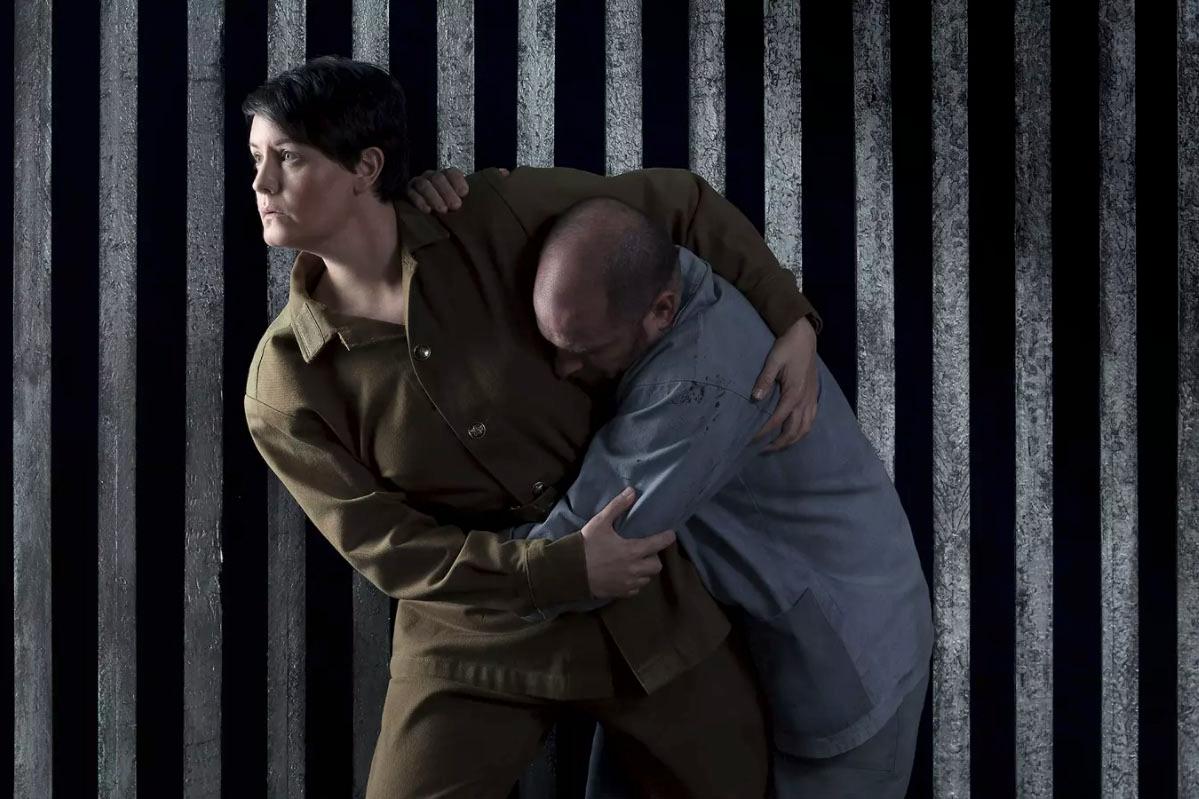

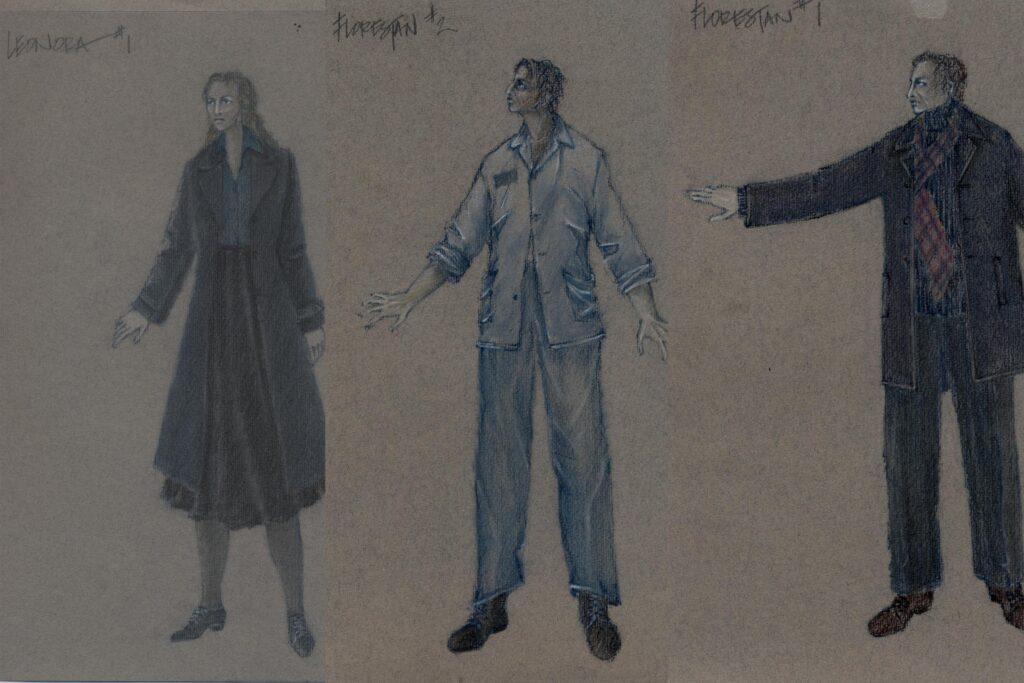

The opera takes place in a prison where the political dissident Florestan is held.

That 2003 production of "Fidelio" was during a season when the opera’s home base at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. was undergoing renovation, so the performances were moved to DAR Constitution Hall.

“We chose to place the orchestra on their stage, and build an acoustic wall in front of it. So the action was very much projected out, like a thrust stage; it was really in the audience's laps,” she said. “We had guard dogs and their handlers running up and down the aisles. I don't think we'd be allowed to do that now.”

Zambello did something else especially striking.

In one scene, she had the entire back of the stage covered with huge video monitors. Each monitor displayed the face of a prisoner shown in closeup. The prisoners’ eyes darted back and forth in expressions of bewilderment and dread. It was a visceral moment that brought the depth of Beethoven’s belief in freedom and brotherhood to the fore.

“I will never forget the pride I felt when RBG (Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg) wrote me a letter (saying) that it was by far the best 'Fidelio' she's ever experienced, and was so moved,” recalled Zambello.

At the end of the opera, Fidelio foils a plot, and Florestan is freed. Fidelio is then revealed to be Florestan’s wife, Leonore. She had disguised herself as a boy so she could find her husband. Her actions also lead to the release of the other prisoners.

“(Florestan) thanks his wife for doing everything for him,” said Zambello. “He talks about the power of women and womanhood.”

Zambello believes this mirrors Beethoven's beliefs, saying he was a great humanitarian. “And that's why I think we should keep revisiting this piece. It clearly keeps speaking to us; and I think to make contemporary analogies is so obvious with an opera like this."

2020 marks 250 years since the birth of Ludwig Van Beethoven and CPR Classical celebrates!

On CPR Classical every weekend Oct. 9 - Dec. 13: Fridays at 12:30 p.m., Saturdays at 6 p.m. and Sundays at 4 p.m.