There’s a growing movement to locate places in Colorado where historic events happened but were never recorded. The Colorado Historical Foundation is on a mission to change that.

“A lot of the telling and recording of history has really been by people in positions of privilege and power,” said Colorado Historical Foundation executive director Cathy Rosset. “We are making up for lost time in the historical record.”

The foundation has received three History Colorado State Historical Fund grants to track down little-known stories about African Americans, the LGBTQ community and Women’s Suffrage in Colorado.

Rosset and her team are establishing a database by searching through old records and dusting off archived newsletters to look for buildings where important events happened.

“It’s really combing through these documents and figuring out who the people were behind the movement. Where did they live? Where did they work? Where did they organize letter-writing campaigns? First, we need to find out what still exists,” Rosset said. “This project will determine how many of the buildings are still standing, using our information on Google Street View and then making limited driving visits.”

It’s the events that happened inside those buildings which the Colorado Historical Foundation wants to bring to life.

“This is an expansive movement to celebrate not just the architecture but what went on in that place,” said Cindy Nasky, the organization’s director of preservation programs.

Suffragist history that's still standing

Sometimes, the foundation’s research hits a dead end. For example, when it learns there’s now a vacant lot where a building once stood.

Conversely, there’s excitement when a historic property is still standing, sometimes after a century, like the 8th Street Missionary Baptist Church in Pueblo, which was a regular women’s suffrage gathering place for African Americans.

“Black women were very vocal in the 1893 campaign and this church became a hub of organizing suffrage events around that church,” Rosset said.

Rosset says the foundation has also discovered that suffragists regularly met for stump speeches in opera houses because of their theater settings. Loveland’s Bartoff Opera House and the Wheeler Opera House in Aspen are two of those locations. The Garden of the Gods held a national Equal Rights Pageant in 1923 and the Molly Brown House welcomed the suffragists regularly.

- In An Era Of Tearing Down Monuments, Colorado Lynching Sites May Gain Historical Markers

- Marble, Colorado, Has History, Art And Character Set In Stone

- The Durability Of Redlining In Denver’s Past Is Shaping Coronavirus Hot Spots Now, Researchers Say

- You’ve Seen The Movie ‘Green Book,’ Here’s Some Colorado Places From The Real List

In 1877, Susan B. Anthony took a train to the Hinsdale County Courthouse in Lake City to campaign for women’s suffrage.

“There was such a crowd of people who showed up to that event, she couldn't hold it inside the courthouse. She had to host it on the steps so that everyone could hear her speak, and apparently it was so inspiring that the very next day, the men and women in that town formed a local suffrage association,” Rosset told Colorado Matters. “Ms. Anthony, who was traveling from upstate New York, was less than thrilled with the rough and rowdy crowds in Colorado's mining towns. So she vowed never to come back.”

One of the country’s only African American resorts

One of the most impressive buildings included in the Colorado Historical Foundation’s story project is Winks Lodge, a social and cultural hub in Gilpin County which entertained such notable jazz musicians and literary figures of the Harlem Renaissance as Count Basie, Lena Horne, Duke Ellington and Zora Neal Hurston.

Before and after performing in Denver, they often made the long drive to Winks to escape the oppression of the city and enjoy the fresh mountain air.

Winks was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

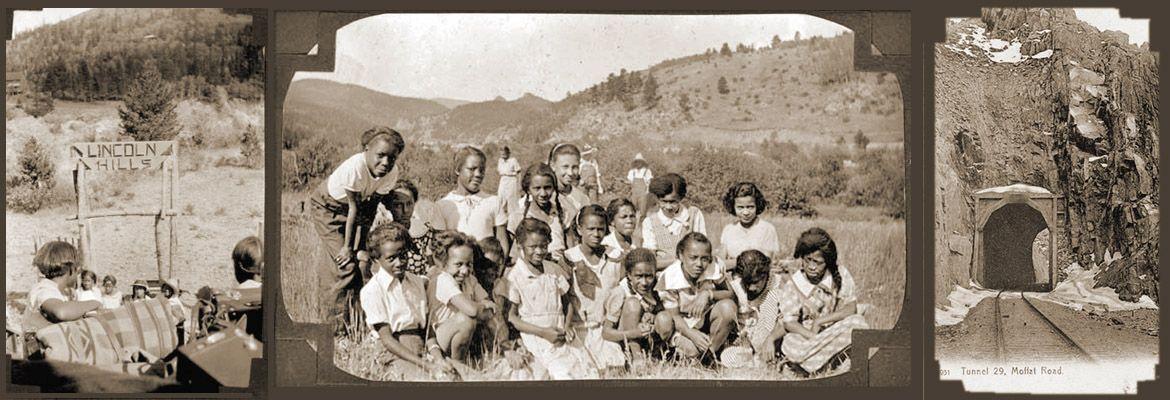

Winks is located in Lincoln Hills, one of just three vacation resorts in the country which catered to African Americans at that time and the only one west of the Mississippi. In the 1920s and through the 50s, due to segregation, there were few places Black families could vacation where they felt comfortable. Lincoln Hills was a destination in the Green Book, the trusted travel guide Blacks used on road trips to find a safe haven.

The Lincoln Hills Development Company got its start in 1922 when two Black entrepreneurs bought 100 acres in Gilpin County from a white developer and divided it into parcels of 25 by 100 feet. The starting price for a plot of land was forty dollars. It took $5 down and five dollars a month to secure a spot.

“It was our American Dream, a mountain place available to us where we felt safe and comfortable,” said Gary Jackson, a Denver County Court judge who was one month old when his family first brought him to Lincoln Hills. “When I was a child I did what any kid does, throwing rocks in the stream and shooting my BB gun. It was where I studied for the Bar and invited 70 people out for the 2008 Democratic National Convention.”

Jackson’s grandfather, William Pitts, was one of the first to build at Lincoln HIlls when he bought four lots in the 1920s. In a letter he wrote to Lincoln Hills Incorporated, he told them that the $40 price tag made him suspicious that the land was “inferior to others, but to my great surprise, I found it to be the most beautiful mountain subdivision that I have ever visited.”

“Back in those years we couldn’t go to Estes Park, Glenwood Springs, or the Broadmoor. You could drive in but you couldn’t be served,” Jackson said. “This was before 1954. Colorado wasn’t any different in terms of de facto segregation.”

“My grandfather, when he first bought the land, he wanted it to be a country club for Black people. That was his plan and that’s why he built more than one cabin up there. And then of course Winks went up and built his cabin, and he’s the one that had lodges for rent and for people to come up and stay at his lodge and he’s the one that had the place for the music and dance and so forth, but our little cabin, we went up just for enjoyment to spend the night and stay up there on the weekend,” said Nancelia Scott-Jackson, Gary Jackson’s 95-year-old mother. “Lincoln Hills was a second home to us.”

In 1927, a summer camp for African American girls was added at Lincoln Hills, run by the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the Denver YWCA. Named Camp Nizhoni, for the Navajo word “beautiful,” the girls would spend a week or two at camp participating in outdoor adventures that were denied them elsewhere. Scott-Jackson was a camp participant.

Camp Nzoni is still thriving, although it was closed this summer due to COVID-19. Nalani Benson Wortham, 14, previously attended the camp as part of an after-school program called “Heart and Hand.” One of her favorite activities is horseback riding, but she also likes the history of Lincoln Hills.

“The history behind it definitely, just to see how far we’ve come because at the time, that was one of the very few places that Black people could go, and now we’re allowed pretty much anywhere,” Benson Wortham said.

She joined the conversation on Colorado Matters and asked Scott-Jackson what advice she’d give about how to deal with discrimination or racism.

“You just stand up for your right and be who you are. Don’t let anyone say you can’t do something or you can’t go here. Always be yourself, and for one thing, always vote. I never missed the vote even for the school board,” Scott-Jackson said. “Do the things that you want to do. If you can’t get through the door, go through the window. Be sure and keep your dreams, always do what you dream of being and just be who you are. And always tell your history.”

Durango's Strater Hotel

When the Colorado Historical Foundation called Durango’s Rod Barker to let him know that his family hotel was in the Green Book, he couldn’t believe it.

“That was a wonderful discovery for me,” Barker told Colorado Matters.

Barker’s grandfather bought the Strater Hotel in 1926, but it was his father who registered it in the Green Book.

“Apparently my dad put the hotel in the book in 1962 as a place welcoming Blacks in their travel,” Barker said. “I can only imagine how difficult it might have been for a black person or a person of color coming to rural Colorado because it may not have felt so welcoming all the way around.”

One of the rooms at the Strater Hotel is named after a Black entrepreneur named Frank Fitchue, whose heroic actions in 1883 saved the First National Bank from robbers who wanted to steal $30,000 in gold and cash.

“One night a local gang of thugs decided they were going to rob the bank and were pressuring Frank to let them in,” Barker said. “His life was actually in danger from this group, but instead of acquiescing, he just simply told the president of the bank about the plan and they arranged to have law enforcement there. When he opened the door to let them in, they had a different welcome than they were expecting.”

Historic LGBTQ Colorado Buildings

The Colorado Historical Foundation grant money will also go toward identifying important LGBTQ sites.

“One of the most significant historic events happened at the Boulder County Courthouse where the County Clerk Clela Rorex issued the first same-sex marriage license in the United States in 1975,” Rosset said.

When the research project is finished, Rosset says the hope is for the History Colorado State Historical Fund to publish a modern Green Book with the Office of Colorado Tourism for history road trips.