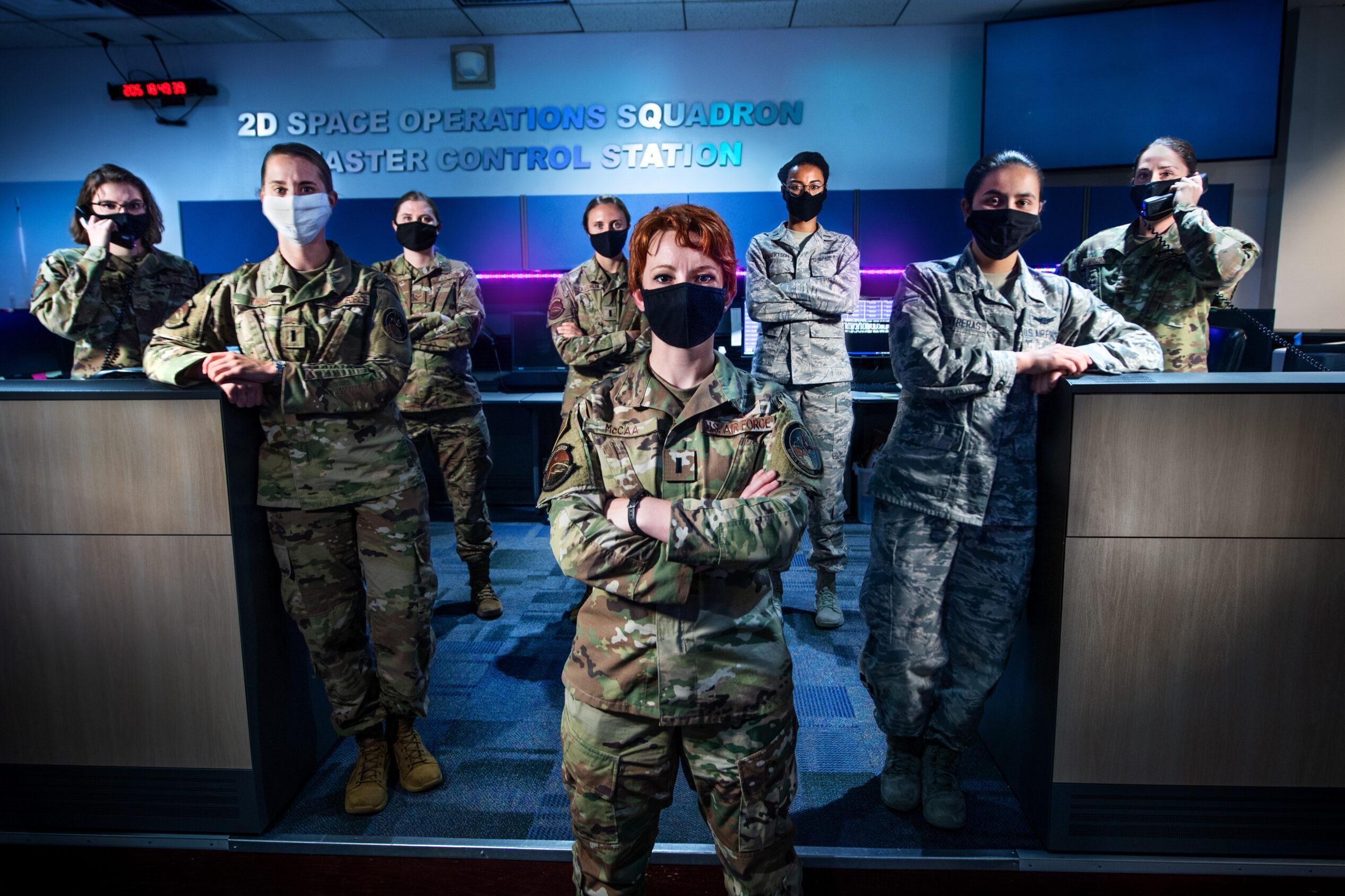

When 1st Lt. Kelley McCaa found out she would be part of the American military’s first all-female space operations crew, alongside a team of women she considers close friends, she knew it would make a bold statement for the newly-formed U.S. Space Force.

McCaa’s squadron, based at Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, operates one of the approximately 30 GPS satellites used by more than 5 billion people around the world.

“Growing up, you don’t see too many women in STEM or women in recruiter videos for the military or science or physics,” McCaa said. “So, for me, I’m hoping that women will see that they have more opportunities than they might’ve realized growing up.”

That all-female team isn’t the only sign that the Space Force is trying to build diversity into its mission from the start.

Nina Armagno was recently promoted as its first female three-star general. As the director of staff for the office of the Chief of Space Operations, she will oversee the day-to-day happenings at Space Force headquarters. And in June, the head of the branch, Gen. John Raymond, addressed the topic in a letter he wrote in response to national uproar over the death of George Floyd. He called racism one of the enemies that service members swore an oath to defend the country against and added the Space Force must be founded on dignity and respect.

“We have an opportunity to get this right from the beginning and we are committed to doing so,” Raymond wrote. “We must build diversity and inclusion into our ‘cultural DNA’ — make it one of the bedrock strengths of our service.”

Some critics worry these public steps only serve to obscure larger systemic problems the Space Force has inherited from the branch of the military it grew out of, the U.S. Air Force.

A troubled legacy

President Donald Trump signed the Space Force into law in December 2019, creating the first new military branch since 1947. Though an independent branch, Space Force still resides within the Department of the Air Force in the same way the Marine Corps rests within the Department of the Navy. Currently, the vast majority of Space Force personnel are Air Force transfers.

A series of reports from Protect Our Defenders, a nonprofit focused on reducing gender and racial discrimination in the military, concluded that the Air Force has the worst problem with racial bias among the military branches. As our partners with the American Homefront Project previously reported, the group found Black airmen were about 70 percent more likely to be court-martialed or face other punishments than their white counterparts.

The Air Force’s own data indicates the problem has been getting worse, not better. Protect our Defenders obtained that data after years of the Air Force blocking its release.

The nonprofit’s president, former Air Force chief prosecutor and retired Col. Don Christensen, said he thought it’s too early to spot whether the Space Force repeats this disciplinary trend. Until that data exists, he said announcements like the all-female space operations squadron and the promotion of Gen. Armagno are positive signs for the branch.

He also believes its distinction as the first ‘all-digital’ service may help. Having the whole force performing high-tech desk jobs may prevent women from some of the same prejudices and stereotypes present in the other branches, where masculine ideals of physical prowess dominate the culture.

Regardless, Christensen said he has not yet seen any substantive action from Space Force leadership indicating diversity is a true priority. For example, the concept is not included in the recently-released 41-page Space Force doctrine, considered a critical founding document for the service.

Progress, or just a photo op?

Yvonne Pacheco recently retired after a 22-year career in the Air Force, a career that culminated in a post as the commanding officer of the U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command in Chicago, IL. She was the only woman of color in a command role in her battalion but lost her rank and command when superiors opposed her taking time off for hysterectomy surgery and inpatient PTSD therapy.

She said a senior officer told her command was “making an example out of her as a Black woman.” Pacheco identifies as Hispanic.

The experience led her to reach out to Protect Our Defenders for legal help. Her rank was reinstated post-retirement and she is now receiving full disability payments for her PTSD.

Pacheco looks at the Space Force announcements, as well as recent news of the first Black Air Force Academy Superintendent and the first Black Air Force Chief of Staff as positive, but ultimately hollow, developments.

“It’s a photo op. [They can say,] ‘See? We like Black people. We like minorities — we promoted them. So, don’t complain anymore, OK?’” Pacheco said. “What we want to see is action. What policies are you going to drive?”

Pacheco lives in New Jersey now but still has a 719 cell number, a reminder of her time serving at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs.

She said problems with gender and race discrimination come down to how the military is organized. As discrimination reports move up the chain of command, she believes senior officers don’t have the proper incentives to act on the charges and instead seek to suppress them to avoid looking bad themselves — a pervasive problem she said requires a fundamental change to the force’s command and reporting infrastructure.

‘We’re going to make you proud’

The Space Force’s Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, Carrie Baker said as a Black woman, she has encountered racism from superiors in her more than two decades with the Air Force but does not believe any of it was intentionally motivated.

Baker argued the recent staffing announcements from the Air Force and Space Force go “beyond window dressing.”

She said starting the force from scratch gives top leaders a chance to set a new standard of zero tolerance for racial and gender bias. And she pointed to several different efforts: outreach initiatives targeted to recruiting women and people of color, mentoring panels to help those service members advance, and a "heavy emphasis" on training senior officers to recognize unconscious bias. She said the Space Force is fostering a culture where a warfighter can speak to superiors about their concerns without fear of retribution.

“Inclusion is not a zero-sum game,” Baker said. “By leveraging our diverse talents, no one is going to be left out. The pie does not get smaller. It gets bigger.”

“Keep your eye on us,” she said. “We’re going to make you proud.”

Looking for sustainable change

Tanya Wood lives in San Antonio, Texas, and works in IT for the Department of Defense. She previously spent two decades with the Air Force, including 8 years as an intelligence analyst — a computer-bound role very much like the jobs performed by members of the Space Force today.

The more traditional work environment did not prevent a culture of misogyny and racism, Woods said. Instead, as one of the only Black women in her position, she was constantly challenged by her white male colleagues and required to prove her abilities and qualifications in ways those men never had to.

Wood said her Air Force career was rife with sexual harassment and assault. She said she was raped while on active duty and then encouraged by superiors not to report it.

Later, in her civilian role, she described severe retaliation for whistleblowing within the Department of Defense, leading to a 14-month suspension without pay as well as a suspension of her security clearance. She said it took 3,000 pages of evidence to clear her name and has yet to receive payment for the months of lost income.

Wood, like Pacheco, worries the Space Force will suffer from the same “archaic process” used when reporting discrimination as its mother branch. She looks at the all-female Space Operations Squadron as a sign of how the Space Force could really build itself better on issues where the Air Force has failed. However, her reading of history leaves her pessimistic.

She points to the Tuskegee Airmen, the decorated Black pilots of World War II, and their legacy in the military.

“Do we still have that level of diversity now?” Wood said. “Was that sustainable or were there more minorities coming into those fields [afterward]? ... It has to be sustainable.”

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Editor's Note: This story has been corrected to more accurately describe Gen. Armagno's title and responsibilities.