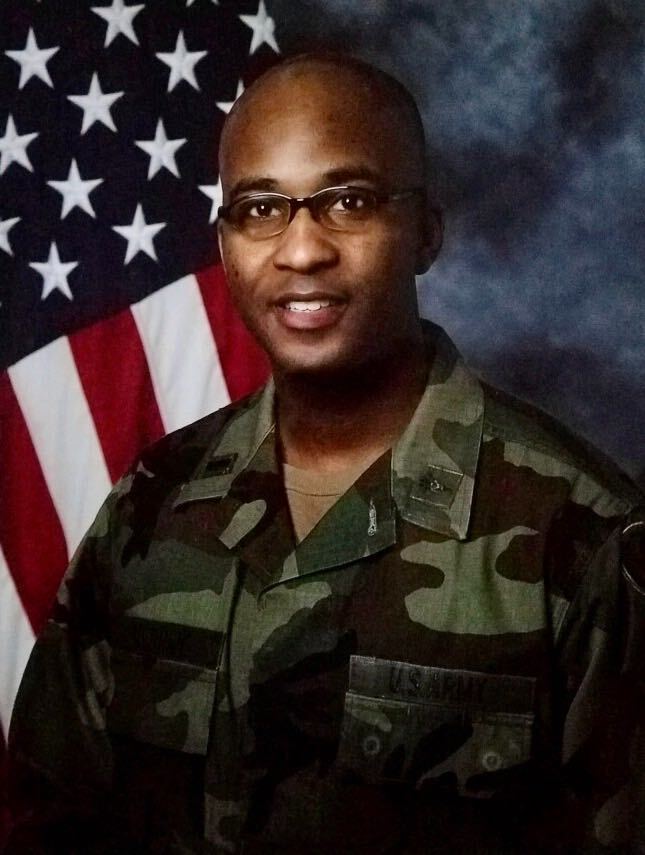

Jared McBride served in the Army for 22 years, rising to the rank of captain. But McBride, who is Black, said his race held him back from other opportunities in the military.

For instance, McBride said that in 2009, he volunteered to become a commander for a unit headed to Afghanistan. But he said the position went to a white soldier who wasn't as qualified. McBride said that - and other bad experiences - chewed away at him for years.

"You're held to this higher standard, which is sometimes impossible to reach," he said.

And sometimes his emotions got him in trouble on the job.

"One of my fellow officers was like man, McBride, you have some anger issues," he said.

McBride eventually left the military and sought mental health care at his local VA in St. Louis. He was diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

And as his treatment continued, he was offered the chance to take part in one of the VA's first programs that address how racism affects veterans' mental health.

The program was the brainchild of several VA psychologists across the country, who had begun to recognize that race-based mental issues were too often ignored.

"Our book that has all our diagnostic criteria, which is the DSM-5, it doesn't recognize racial trauma," said Dr. Lamise Shawahin, a former VA psychologist who now teaches at Governor's State University outside Chicago.

The DSM-5 sets forth the criteria psychologists use to diagnose patients.

"Experiencing racism was turning into people being labeled with pathology when really they were just experiencing racism," Shawahin said.

Shawahin and other VA psychologists zeroed in on how racial discrimination contributes to things like post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety.

Studies have shown that veterans of color have higher rates of mental health issues like PTSD, compared with white veterans, even when controlling for where they were deployed and the pressures of returning from war.

Shawahin said part of the problem is that the military pushes the concept of colorblindness, but that can exacerbate race-based stress by emphasizing sameness.

"This idea — 'we're all green' — and these types of slogans, they instill the notion that racial differences are not important in the military," she said.

Veterans of color also don't use the VA's mental health services as much as they could. And some stop seeking help altogether because they become dissatisfied with their care.

Shawahin and other VA psychologists were awarded a grant in 2018 to create the program to help veterans identify racism as the source of at least some of their anxiety. The program holds group meetings for veterans of color.

VA officials declined to be interviewed about the program or provide information about it. But several veterans explained how the sessions worked.

McBride joined one of the first small groups in St. Louis. He said veterans sometimes walked into a room buzzing with jazz music. He said the VA psychologist who first led his group, Dr. Maurice Endsley, started by writing a topic on a whiteboard.

"Let's just say police brutality," McBride said. "He would get into 'what does that look like to you? And how do you feel about that?'"

McBride said it was the first time anyone had ever talked to the veterans in his group about how the racism they endured every day affected their mental health.

"We got some guys holding on to this thing for years," McBride said. "And so when you bring up different topics and different things, sometimes it gets emotional and explosive."

Army veteran Bernadette Spiller cautiously joined one of the first small groups in St. Louis in 2018 after she saw a flyer in the VA hallway.

"I didn't want to go to therapy, because I looked at it as a sign of weakness," she said.

But she sat herself down at a small group session with a facilitator who started talking about racial microaggressions. And after a few meetings and listening to other veterans speak, Spiller realized that many stressors in her life were triggered by racism.

"It kind of gives you like an arsenal of being able to go into your little treasure chest and say, 'OK, well I've heard that somebody experienced it this way,'" she said.

Veterans said the group gave them mechanisms for coping with racism, so they can feel safer while grappling with painful memories and experiences.

Keisha Ross, one of the VA psychologists who now heads the St. Louis group, recently spoke on a virtual panel alongside other psychologists about their work.

She said the intimate group sessions can lead to a collective level of support and engagement among veterans.

"They started building lists of businesses and those kinds of things that were owned by people of color that they could support, as well as those within the group themselves, who have businesses," she said of one cohort she co-facilitated.

She said she and a group of VA psychologists do consultations via Skype that provide basic training for psychologists who might want to start similar groups.

Even the pandemic hasn't stopped the veteran meetings. Everyone continues to get together on Zoom.

"Out of two years, I probably missed one or two sessions," McBride said. "They make you feel welcome."

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2020 North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC. To see more, visit North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC.

9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))