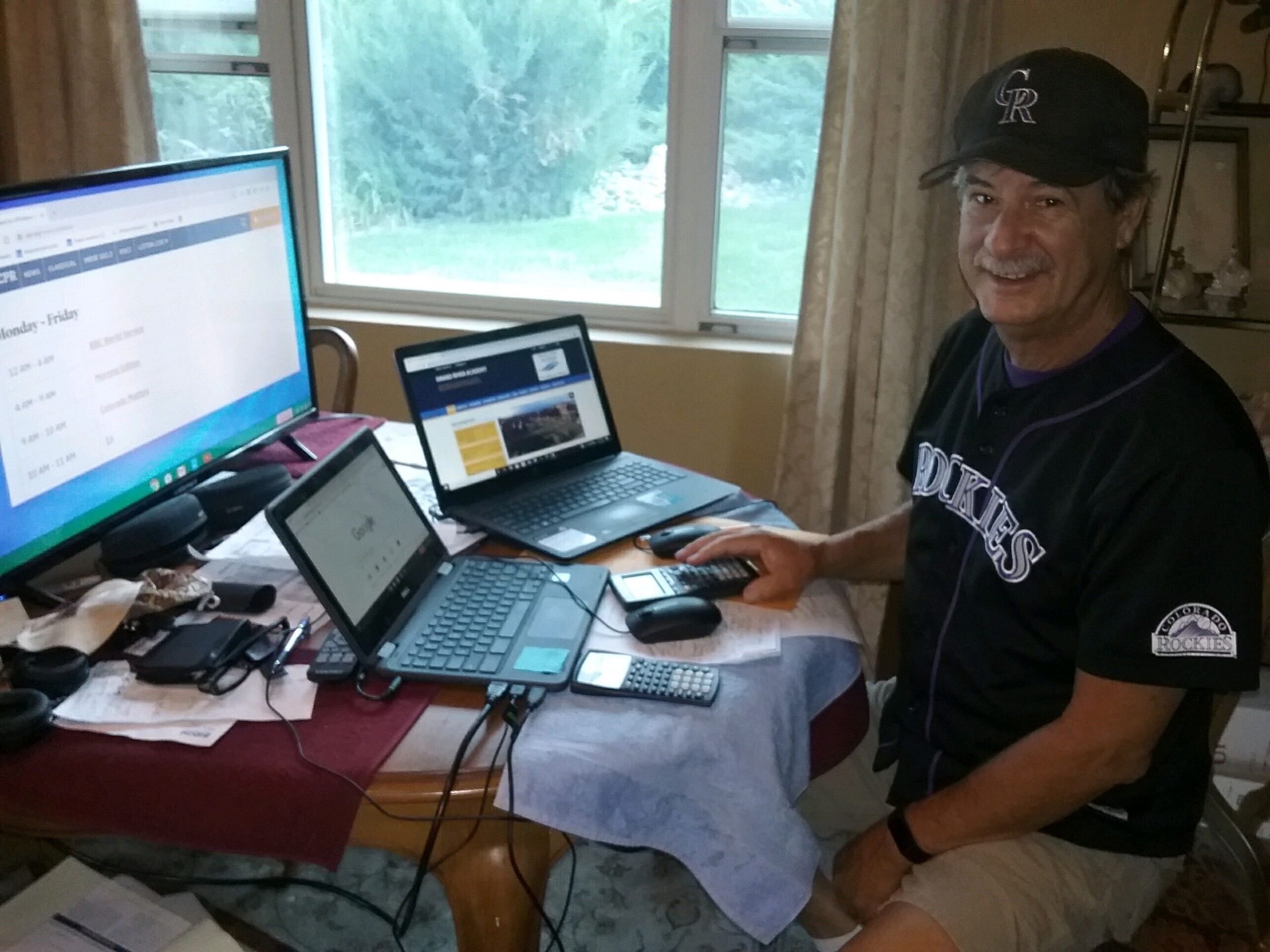

When high school science teacher Mike Pewters began the school year from his kitchen table in Grand Junction in August, he immediately faced two pressing challenges: navigating complex, brand-new curriculum software, and figuring out how to teach more students than he’d ever had — about 250.

“It’s triage. It’s Apollo 13,” the 63-year-old Pewters joked, referencing that space mission where everything kept breaking. “So we’re going to fix one thing after the next. We’re going to survive. We’ll get through it. And then eventually it will get better.”

Starting Monday, it should. Two new high school science teachers will begin online instruction, which should cut Pewters’ class size by about half. One month after schools opened, this shifting of teachers online is happening all across sprawling District 51, which covers most of Mesa County. Twice as many families opted for virtual learning than school officials expected, with more pivoting to online as the semester progresses.

Getting extra teachers for online learning, however, hasn’t been simple. The district had to take some out of the in-person classrooms. That was even after school had started and they’d settled in with their students.

For those teachers, it was a “wrenching change” said Rick Peterson, president of the Mesa Valley Education Association. His group works like a union for District 51 teachers.

“I don’t think you’ll have to look too far to find online teachers who are going to have great reservations about how things are going,” he said.

Other issues include online elementary school curriculum that arrived late after nationwide demand caused a backlog. Teachers are expected to begin using those materials Monday, as well. Peterson said it’s easy to see why those teaching online are overwhelmed.

But he also stressed that it’s still early in this unprecedented school year.

“And it’s still very much in flux” due to this movement of teachers and students, Peterson said “So you can expect it to be chaotic.”

District 51 Superintendent Diana Sirko said all these unknowns have been hard on families, too. She keeps a scrapbook of emails from parents she calls “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.”

The “bad” and “ugly” ones can be tough to read.

“I think it’s hard because there’s so much unpredictability,” Sirko said. “You can’t yell at the virus, so you can kind of take it out on us. And I get that frustration.”

One of the most common complaints she’s received is that families think the district should have been able to better predict the number of online students. Sirko said the district’s estimate of 1,000-1,500 online kids was based on surveys it sent out in July. By the time school started in August, however, closer to 3,000 students were learning online.

Many families had changed their minds, “and I get that,” Sirko said, “because some parents, until they know what your plan is, they don’t know whether they’ll do online or face-to-face.”

And she added that no one in education has ever dealt with a situation like this.

But even as unsettled as this semester's start has been, science teacher Pewters can feel himself emerging from crisis mode.

When he starts to glaze over in front of the computer, he can look out his window and see Colorado National Monument. As he’s gotten a grasp of the teaching software he’s been able to go from a “grading machine” to being able to help more students one-on-one — including a young woman who had just moved to town and was facing online classes with complete strangers.

In his 21 years of teaching, Pewters said making these connections with students has always meant a lot to him. They are harder to forge virtually, but it’s still possible.

Yes, sometimes teaching online can wear you down, he explained.

“But then you have a student that says something like, ‘Wow, I never learned this before. This is really cool,’ or ‘Thank you so much for helping me out,’” he said. “That always brings you back.”