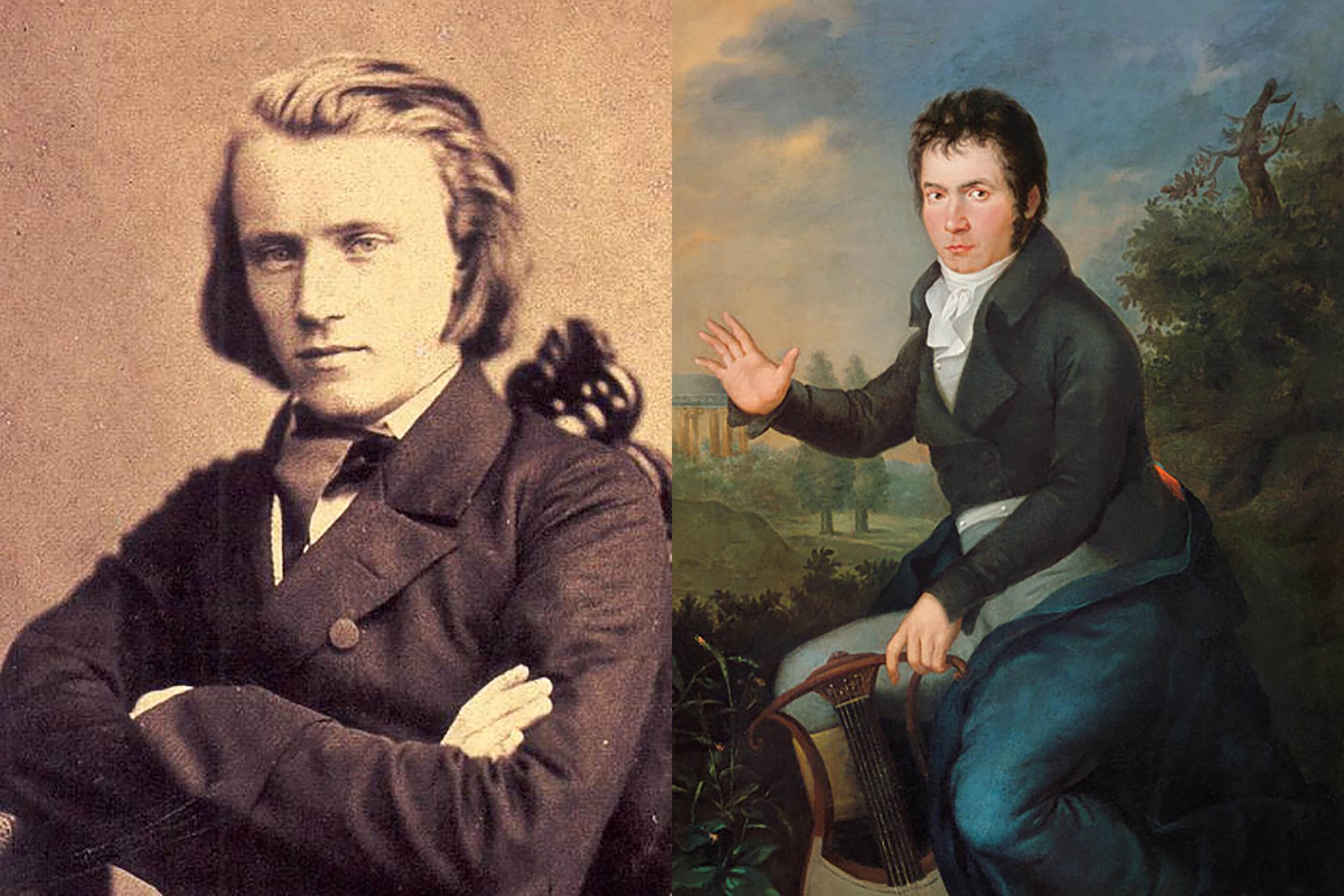

Some years ago, I was stopped at a traffic light and heard Johannes Brahms' Symphony No. 1 on the radio. It dawned on me (after many times listening and playing it in orchestras on the violin) that Brahms channeled his predecessor, Ludwig van Beethoven.

Have a listen here to a snippet of Brahms' first movement from his Symphony No. 1:

What you hear (at least what I hear) is a familiar rhythm. It’s the Bah, Bah, Bah, Bah from Beethoven’s famous Fifth Symphony open.

The young Brahms cleverly passed this famous rhythmic tattoo among the various voices in the orchestra. Sometimes it’s in your face. Sometimes it’s subtle like this:

Brahms didn’t stop there.

There are other nods to Beethoven in Brahms' First Symphony that have been well pointed out. For instance, the nature of the broad, stately theme in Brahms’ finale has been compared to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

When critics of the time pointed out the similarity to Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, Brahms retorted, “Any ass can hear that."

Brahms was well aware that he stood in Beethoven's shadow. (Beethoven, after all, is classical's Greatest Of All Time, or GOAT).

He opined, "You have no idea of how it feels — always to hear the tramp of such a giant [Beethoven] behind you."

That was a lot of pressure. Brahms was born six years after Beethoven died and he was just 20 years old when composer and music critic Robert Schumann complicated matters by declaring him Beethoven’s heir.

The pressure of such high expectations terrified him. That’s why Brahms took nearly two decades — from early doodles and sketches to final product — to complete that first symphony. Once he cleared that hurdle, the music flowed freely. He completed his other three symphonies each in less than a year.

The looming shadow of Beethoven was and is legendary; intimidating numerous composers who followed him. Besides Brahms, great symphonists like Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Mahler felt his presence.

David Korevaar, a concert pianist and Distinguished Professor in the College of Music at the University of Colorado Boulder, said Beethoven had a similar effect on his contemporaries, including his teacher.

“Poor Haydn,” Korevaar said.

Franz Josef Haydn realized his student’s genius and changed his focus as a composer. Haydn pretty much stopped writing instrumental music and turned his attention largely to choral works instead.

“Beethoven by the late 1790s made such an impact that Haydn — who, after Mozart’s death, briefly got to revel in being the greatest composer in Vienna — found himself again eclipsed,” Korevaar said.

Two centuries later, Beethoven continues to intimidate.

“There's this kind of masterpiece complex where we say, 'Do you dare to play this music?' Well, why not?" Korevaar said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Korevaar challenged himself to record all 32 Beethoven Piano Sonatas, mostly in his home living room The goal was to complete the cycle in 60 days. He did it in 41.

2020 marks 250 years since the birth of Ludwig Van Beethoven and CPR Classical celebrates!

On CPR Classical every weekend Oct. 9 - Dec. 13: Fridays at 12:30 p.m., Saturdays at 6 p.m. and Sundays at 4 p.m.