The problem starts at the top.

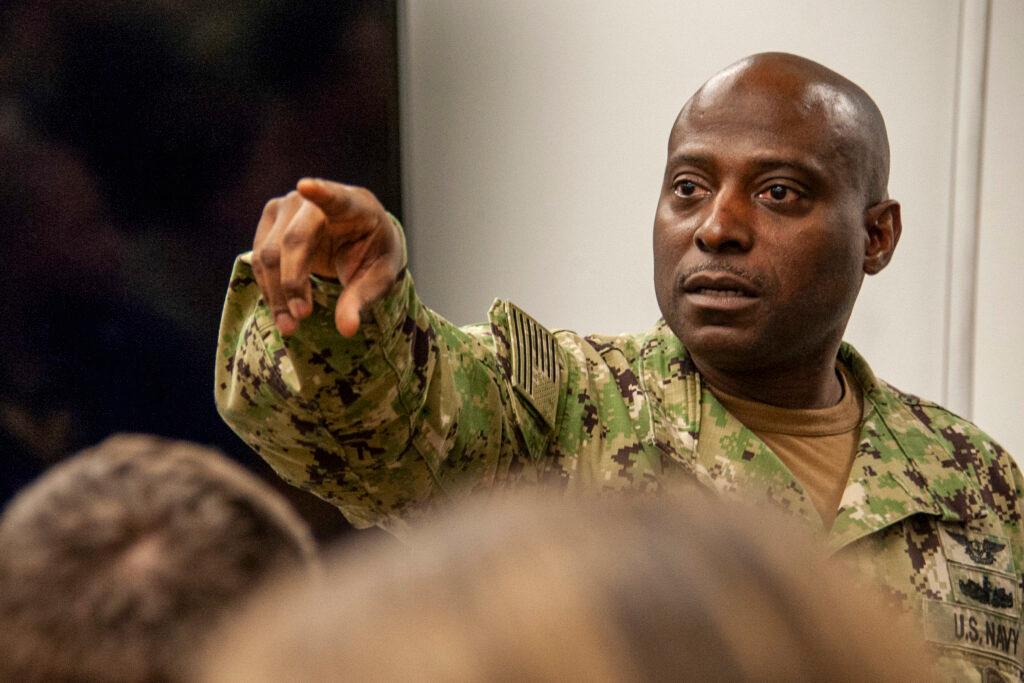

According to data provided by the One Navy Task Force, of the 268 admirals in the Navy, only 10 are African-American, and most are rear admirals, like Alvin Holsey who is heading the task force for the Chief of Naval Operations. There are no Black admirals at the two highest ranks.

Holsey concedes those numbers are small. He said building an admiral is a 20- to 30-year commitment, and someone has to be willing to guide that young officer.

"As a Black officer in the U.S. Navy, I will tell you I've mentored more people who don't look like me than do look like me," he said. "Somebody who doesn't look like me had to reach out and engage in my career."

African Americans comprise about 13 percent of the U.S. population, but roughly 8.1 percent of Naval officers are Black, according to a 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service.

So the pipeline is small, and many Black officers just become exhausted as they work their way up the chain of command, said Keith Green, a retired lieutenant commander. He recently wrote the book "Black Officer/White Navy."

"It is not simply just unconscious bias," Green said. "There are active behaviors that are happening to people, because they don’t like working for a Black person or a minority, and they don’t like having one be their supervisor."

Not everyone whom African American officers encounter is a problem, but Green said the extra effort to work around troublesome colleagues takes its toll on Black sailors' careers.

"Not only do you have to do all the other stressful things that any military person has do to," Green said, "you have to play that double game of trying to figure out why you're being treated differently or what's happening to you. Why is something happening to you that isn't happening to other people?"

Retired Rear Admiral Sinclair Harris heads the National Naval Officers Association, which has worked for 50 years to promote diversity in the sea services. He said it takes hundreds of ensigns to eventually make one admiral - or what the Navy calls a flag officer.

"You got to bring more people in in the beginning," he said, "so that the quality cut that you're going to have when you get to senior officer and get to flag officer you have enough people in the pot.”

He called it "Death Valley" — that point where junior officers opt-out to end their careers.

Graduating from the Naval Academy is the most well-worn path to the rank of admiral, but fewer than 6 percent of the current class at the Naval Academy is Black. Admiral Harris, who was rejected when he applied to the Academy at the beginning of his career, said one solution is mentoring officers coming through less traditional paths.

"When you have one out of 20 diverse candidates going up for flag officer in a community and they decide, you know what, I just got this high paying job at IBM .... now you're down to zero and you have to look at that pipeline, and that pipeline is anemic," Harris said.

The Navy is more diverse at the lower ranks. Nearly 20 percent of enlisted sailors are African American. But Force Master Chief Huben Phillips, who is part of the One Navy Task Force, said sailors can face discrimination in the ranks.

"Throughout my 31 years when I've seen racial discrimination against me, I knew what the policy was; I knew it was wrong," Phillips said. "But when you're in the minority, you just kind of put your head down. You think about self-preservation. You think about your family. You think about the bigger picture."

At the moment, the Navy is encouraging enlisted and officers alike to speak up. One Navy Task Force is scheduled to issue its report in December.

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2020 North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC. To see more, visit North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC.

9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))