Kris Garcia had never thought much about politics before 2012, when an organizer at a community meeting told him about a new idea in Colorado.

The organizer was working on a new campaign for paid family leave. She asked Garcia and the others whether the state should guarantee workers could take paid time off for childbirth and family medical emergencies.

Garcia instantly thought back to his father’s death a few years earlier, when the demands of his retail job kept him from the hospital bedside. So he agreed to help, thinking that the new law would pass easily.

“How many other people are dealing with the emotional trauma? When it finally hits them: I wasn’t there to say goodbye,” he said.

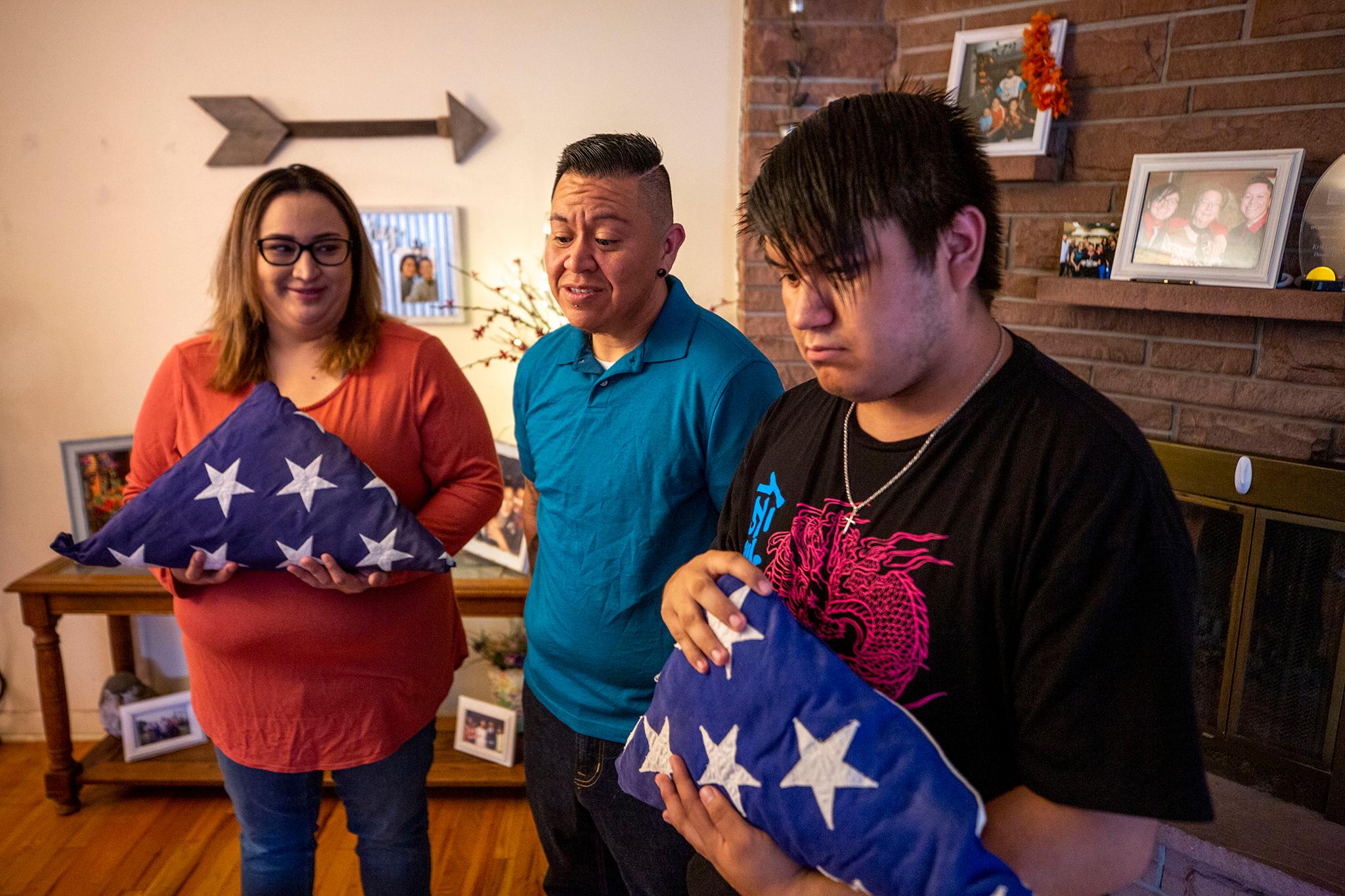

Eight years later, Garcia has been to the state capitol at least 15 times, flown to Washington, D.C. and become a face for the cause in national campaigns. He’s watched Colorado’s Democratic state lawmakers introduce paid leave bills every year since 2014, only for their coalitions to fall short, sometimes by just a few votes.

“What I quickly found out is anytime you get involved in these kinds of issues — it’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon,” said Garcia, now a co-chair of the national workers' rights groups 9to5.

Now, that marathon has entered new terrain. Voters across Colorado will decide the fate of a paid family leave initiative in this fall’s election. A win would make Colorado the ninth state, in addition to Washington, D.C., to create a publicly administered paid leave benefit. It would also institute new fees on workers and employers to fund the major new government program.

Advocates say this popular vote is the ultimate end-run around the Republicans, centrist Democrats and business lobbyists who have helped to stop past efforts in the legislature. Now, they’ll test the strength of the working-class alliance they’ve built over the last decade.

“The thought of it being on the ballot — it made me elated to know that it was finally in our hands,” Garcia said.

Sensing an opportunity in this turbo-charged election, progressives are pouring significant resources into their effort: The Sixteen Thirty Fund, a national dark money nonprofit, has given nearly $3 million to the campaign itself. But the ballot initiative could be a risk for reformers too: An election loss would make it more difficult to try again at the capitol.

“In Colorado, we take voters’ intent very seriously,” said state Sen. Faith Winter, who has championed the cause for years. “If it doesn’t pass, we need to have conversations about why.”

Still, she said, “giving the power to the people” could finally provide a breakthrough on an issue that has eluded progressives for years. The new law would start to go into effect in 2023.

But opponents of the initiative warn that it adds one more burden for businesses as they struggle to regain their footing amid the pandemic. They argue the state should offer incentives to get companies to provide leave on their own, instead of requiring new benefits for workers.

“I think this process will define Colorado,” said Dave Davia, CEO of the Rocky Mountain Mechanical Contractors Association and a co-chair of the No on 118 campaign. “Will we be looked at as the free thinking, free spirited state that is made up now of unaffiliated voters, or are we going to be tagged and put in with states that are more left-leaning?”

What the law does:

If a majority of voters approve, the law would:

- Guarantee that every employee in Colorado can take 12 weeks of paid time off, starting in 2024, for:

- the birth or adoption of a child

- care for themself or a family member with a serious health condition. The definition of “family member” includes any individual with a “significant personal bond that is like a family relationship.”

- circumstances related to a family member’s active-duty military service

- safety from domestic abuse, sexual assault and stalking

- Collect a fee on salaries to fund the program starting in 2023. It would start at 0.9 percent of each workers’ wages, split between the employer and the employee, though it could rise to 1.2 percent. Businesses with 9 or fewer employees would not have to pay the employer half of the premium. Local governments and employers with equivalent paid-leave plans would be exempt. Self-employed people and gig workers could choose to pay into the program and be eligible for the benefit.

- Pay wages for employees on leave. In 2024, the maximum weekly benefit is estimated to be $1,100. Lower-wage workers would get up to 90% of their wages covered, while higher wage workers would get a smaller portion replaced.

Selling it to the public.

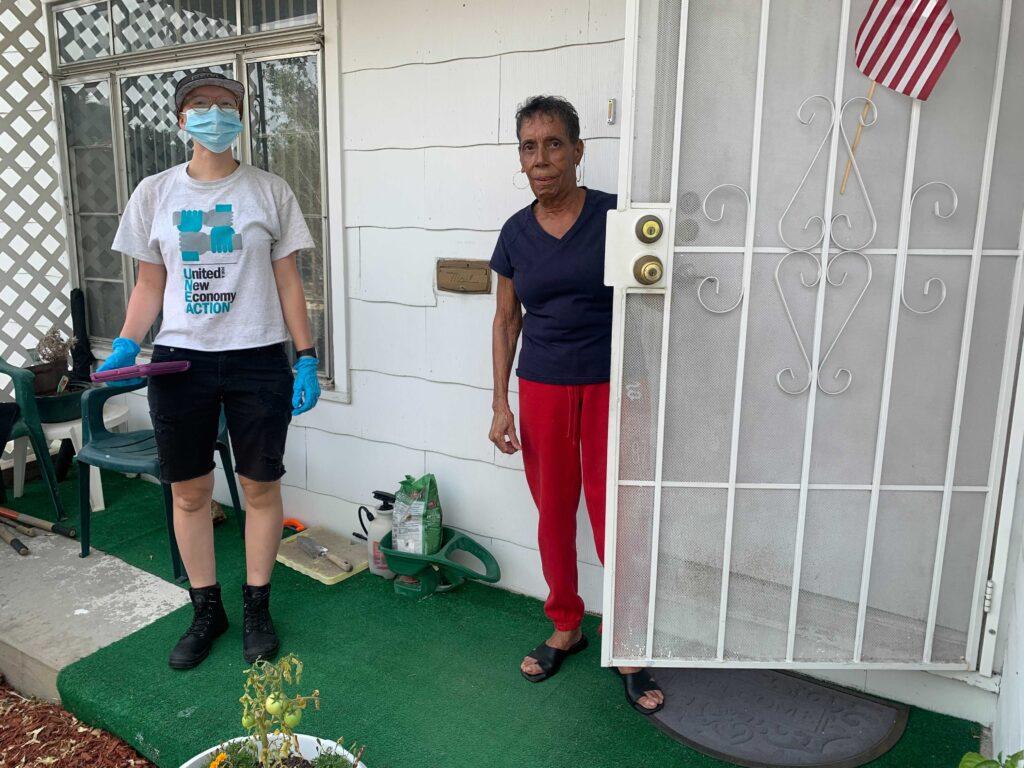

Quinn Mills, 24, walked the sunny blocks of west Aurora’s diverse, working-class neighborhoods on a recent Tuesday afternoon, wearing a disposable mask and tapping at an iPad through plastic gloves.

Mills is a paid canvasser for United for a New Economy Action, a nonprofit supporting the paid leave campaign. One of the first residents they encountered was Yvonne Neal, a Democratic voter who seemed skeptical at first.

“I’ll be 77 in April. The only thing I take care of is my dog, and I did that today, so how does that concern me?” Neal asked. “I mean, I help where I can.”

“Sure,” Mills said amiably. “This is an issue that affects all Coloradans, especially with the COVID crisis. If people are having to quarantine for two weeks and they’re not getting paid while they’re gone, that’s an economic crisis on top of a health crisis.”

In fact, Colorado lawmakers already passed a law this year to guarantee workers have paid quarantine time, plus a handful of sick days per year — but advocates are using the pandemic to focus attention on a bigger labor fight.

Paid family and medical leave is an increasingly popular perk employers offer to their higher-wage workers, but it’s much more rare in lower-wage jobs, such as in the retail and service sectors. Only 16% of private industry workers nationwide have paid family leave, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That message appeared to resonate as Mills and other canvassers went from house to house in the neighborhood. Instead of trying to persuade middle-of-the-road voters, their goal is to boost turnout among voters who likely agree with the policy, but might not cast a ballot.

Soon after meeting the canvasser, Neal revealed that she was already planning to vote for the measure.

“We have to help people. We have to help our neighbors,” she said.

Colorado voters will make a historic decision.

Proposition 118 breaks new ground: It’s the first time a state’s voters have been asked to create a paid family leave program. California lawmakers approved the first such program in 2002. And in the other seven states with similar benefits, the laws also came out of their legislatures.

But by this spring, Colorado’s most prominent paid leave advocates lost faith in that route.

"After years of coming to the table and negotiating and compromising, we really just said, 'enough is enough. We can’t afford to wait any longer,'" Sen. Winter said late in April. She announced her support for the ballot initiative as the latest attempt in the state Capitol faltered.

This year’s defeat was especially bitter. Democrats control the state government and paid leave is a top priority for the party, but internal disagreements stalled the effort. Gov. Jared Polis signaled his opposition to the publicly funded model early in 2020, instead supporting a new “private mandate” approach that fractured support among Democrats.

“I think Colorado is at the vanguard of supporting working families… and at the same time we have faced an uphill battle, often facing hundreds of lobbyists,” said Jessie Ulibarri, a Democratic former state senator who sponsored the first paid leave bills.

Davia pushed back on the idea that lobbyists alone have stopped the bill from passing. He argued that business representatives negotiated in good faith, and that they were willing to entertain Gov. Polis’ suggestion of a private mandate.

“We engaged, and we were fully in support of exploring that opportunity, to see if that’s not the compromise that was able to help us bring this five-year journey to a close,” Davia said.

The reformers’ decision to go to the ballot instead, he said, erased years of negotiation. Now, voters will have a simple yes-or-no vote, although lawmakers will have the power to revise the law.

The ballot initiative has the support of a majority of the state’s lawmakers, even though Democrats didn’t pass similar bills when they had a chance. Meanwhile, Gov. Jared Polis is “neutral,” his office said.

Joseph Kabourek, the campaign manager for the initiative, said he’s confident that Colorado voters will approve what the legislature wouldn’t.

“Coloradans have a history of leading on policy initiatives on the ballot. Just look at what happened with marijuana,” he said, referring to the resounding popular vote to legalize cannabis in 2012.

But voters here have rejected plenty of other progressive priorities.

An attempt to create a universal health care system was rejected by nearly 80% of Colorado voters in 2016. And they have very rarely agreed to give more money to the government, rejecting the vast majority of tax increases.

Colorado voters “do their homework, especially when it comes down to the fiscal side of the state. That meets resistance time and time again,” Davia said.

The opposition campaign to Prop 118 will focus in large part on the costs of the measure. Starting in 2023, the law would require many employers and employees to pay premiums equal to 0.9% of the worker’s wages. That number could rise to 1.2% to cover growing costs. Businesses that offer their own equivalent paid-leave benefits would be exempted from the premiums.

Davia argues the $1.2 billion the program would collect in its first year is the equivalent of doubling the state’s corporate tax and boosting payroll taxes by a fifth. The measure also will increase costs to the state government, which will have to pay about $10.9 million in premiums for its own employees. And opponents say the costs could go higher in some scenarios.

“Employers are concerned about this, businesses are concerned. Shucks, we’ve had Democrats and our governor who are concerned,” Davia said. “This isn’t about party. This is about finances.”

Still, the paid leave campaign does have an advantage over other costly ballot measures of the past.

Its funding comes from a fee, not a tax. That means it escapes several provisions in state law meant to highlight the cost of new taxes: It doesn’t appear on ballots in all-caps, and the ballot question doesn’t lead with a warning about hundreds of millions of dollars in costs.

This was nearly a decade in the making.

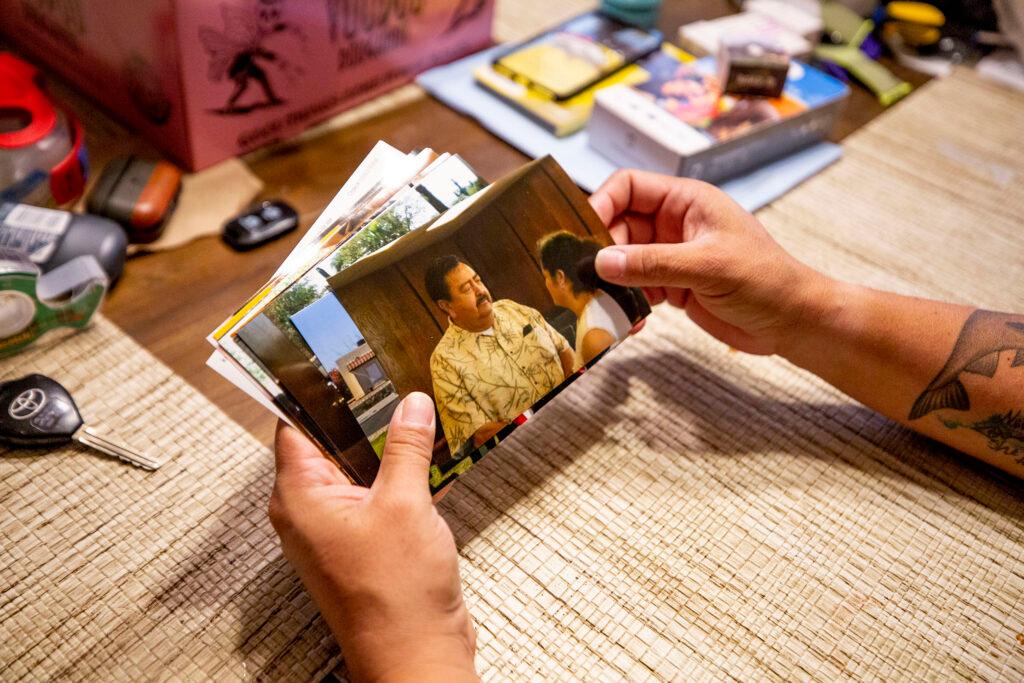

In his visits to the Capitol, Kris Garcia has often shared the story of his father’s passing in 2009.

He was working at an auto parts store and was only able to get a few days off to help his father recuperate from a surgery in Texas, he said. When complications arose from the surgery, Garcia had already returned home to go back to work. He was dealing with a customer when his father’s doctor called the store with bad news.

“I’ll never forget it. I’m at the parts counter, dealing with a customer, and trying to make my dad’s final decision,” Garcia said. “Mentally, it took a toll on me.”

Now, he’s telling that story to friends and neighbors, as well as in video messages. The campaign is also focusing on what the benefit would mean for new parents, who often return to work just days after childbirth. Research shows that California’s paid leave law was associated with significant improvements in children’s health, as Health Affairs reported.

But for every worker’s story, opponents to the campaign are raising concerns about unintended consequences, especially for small businesses.

Gail Lindley, the owner of Denver Bookbinding Company, has long opposed the paid leave effort. Skyrocketing property taxes and the decline of print have already set her back, she said. She can ill afford the premiums, she said, or to lose employees for months at a time.

“Small business really works hard to treat their staff correctly — with kindness, with common sense, with compassion. The companies that [paid leave advocates are] addressing, that’s not in my personal world,” she said.

The smallest companies — those with nine or fewer employees — won’t have to pay premiums, but they will have to allow eligible workers to take months of leave, and hold their job for their return.

Supporters counter that the government-funded leave will help even the playing field between small and large businesses, by making what is now a perk into a universal benefit. And if they succeed, they could deliver one of the biggest workplace changes that Colorado has ever seen.

“I’m feeling confident,” Winter said. “We always knew that this is an incredibly popular policy among voters, and ultimately ballot initiatives are about the power of the people.”

Editor's note: This story was updated Sept. 30 to correct the amount the state government would pay in premiums.