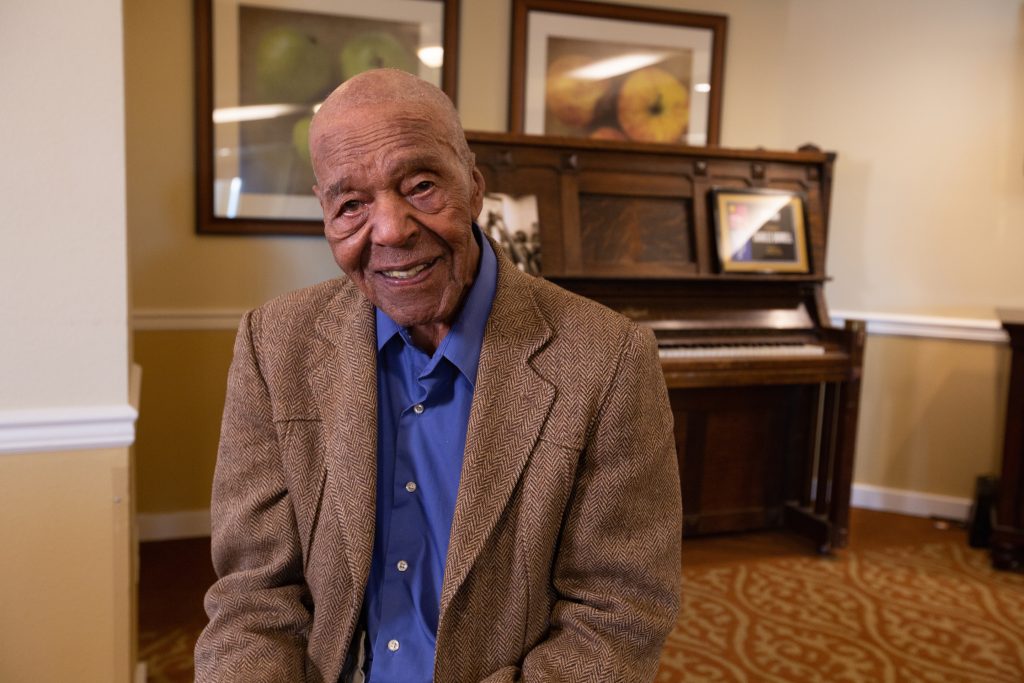

Burrell turns 100 years old on Sunday, October 4th. CPR Classical’s Ray White interviewed him after he turned 99. Listen to it here.

When Charles “Charlie” Burrell, who grew up in 1920s and 30s Detroit, was in seventh grade, his music teacher walked into the classroom and asked if anyone wanted to join the orchestra. Burrell took the last instrument left in the storage locker: a gigantic string bass.

Burrell later heard the San Francisco Symphony play Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony on the radio. He was hooked and it became his goal to someday play under that orchestra’s director, Pierre Monteux. So Burrell began a diligent practice schedule, mixing both classical and jazz music into his studies.

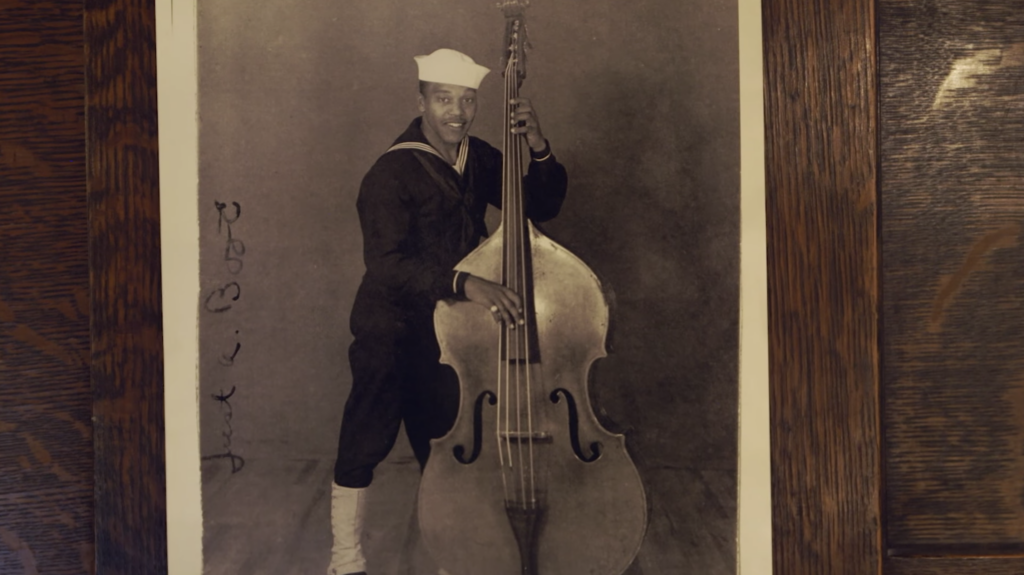

Burrell wanted to be a music teacher. That goal was interrupted by World War II. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Base in Chicago. There, he played in an all-black big band with greats such as trumpeter Clark Terry and trombonist Al Grey. He also took advantage of the nearby Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Northwestern University to continue mastering classical bass.

After the war, Burrell went home to Detroit and attended Wayne State University on the GI Bill so he could continue his music education.

But he was told he would never find work as a Black music teacher.

He decided to leave college. Burrell’s mother had moved to Denver, where her family was from, so he hopped on a bus and headed west.

In Colorado, Burrell landed an audition with the Denver Symphony Orchestra. (It was still a growing local orchestra then. Now it’s the Colorado Symphony.) Burrell became the first Black member of the orchestra in 1949 and played there for 10 years.

And then Burrell’s dream of playing with the San Francisco Symphony came true. He auditioned for an open seat in the bass section and became that orchestra’s first Black member.

A newspaper reporter picked up the story. Journalists like catchy titles, so Burrell was described as the “Jackie Robinson of Classical Music.” That title stuck and is used a lot when referring to Burrell. He was certainly one of the pioneers but he wasn’t the first Black musician to get a contract to play in a major orchestra as Robinson was the first Black athlete to play in baseball’s major leagues. That distinction goes to bassist Henry Lewis who was hired to play with the LA Philharmonic in 1948. And two years before Burrell joined the SFS, cellist Donald White became a member of the Cleveland Orchestra, one of the “Big 5” orchestras in the United States.

Burrell helped break the color barrier in education, too. He was one of the first professors of color at the renowned San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Burrell was with the San Francisco Symphony for five years. Then an earthquake hit. It shook Burrell up so much, he got on a bus the next day to go back to Denver and rejoined the Denver Symphony Orchestra.

Burrell stayed with the symphony until his retirement in 1999 at the age of 79. All that time, he continued to play in jazz bands and performed with legends like Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald.

He mentored young musicians including legendary jazz bassist Ray Brown (husband to Ella Fitzgerald), keyboardist George Duke, and niece, Denver-born, multi-Grammy award-winning vocalist Dianne Reeves..

And then after retirement? He slowed down… some. He continued to play jazz with his musical family and with the Charlie Burrell Trio.

He was given the Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award in 2015. In 2019, for Burrell’s 99th birthday, the Colorado Symphony performed Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony — the very piece that inspired Burrell to pursue a career in classical music when he was a teen in Detroit.

Not much has changed since Burrell first took a chair in the Denver Symphony. The symphony still has only one Black member. It’s certainly not alone. According to a 2014 study, only 2 percent of musicians in American orchestras are Black. Performers of color are often relegated to guest soloist positions. But there are groups like the Sphinx Organization that help talented music students and young professionals with the hefty costs of orchestra auditions. Time will tell if the disparities improve.

Thanks to Colorado independent filmmaker Vohn Regensburger who is producing a documentary on Burrell’s life.