On Saturday, March 20, Saul Sanchez, 78, woke up and went into work for an extra shift at the JBS meatpacking plant in Greeley.

He was unusually tired and had gone to bed the night before without eating, but Sanchez had worked on the plant's fabrication line for 30 years and wasn’t one to miss a shift.

It would be the last shift of his life.

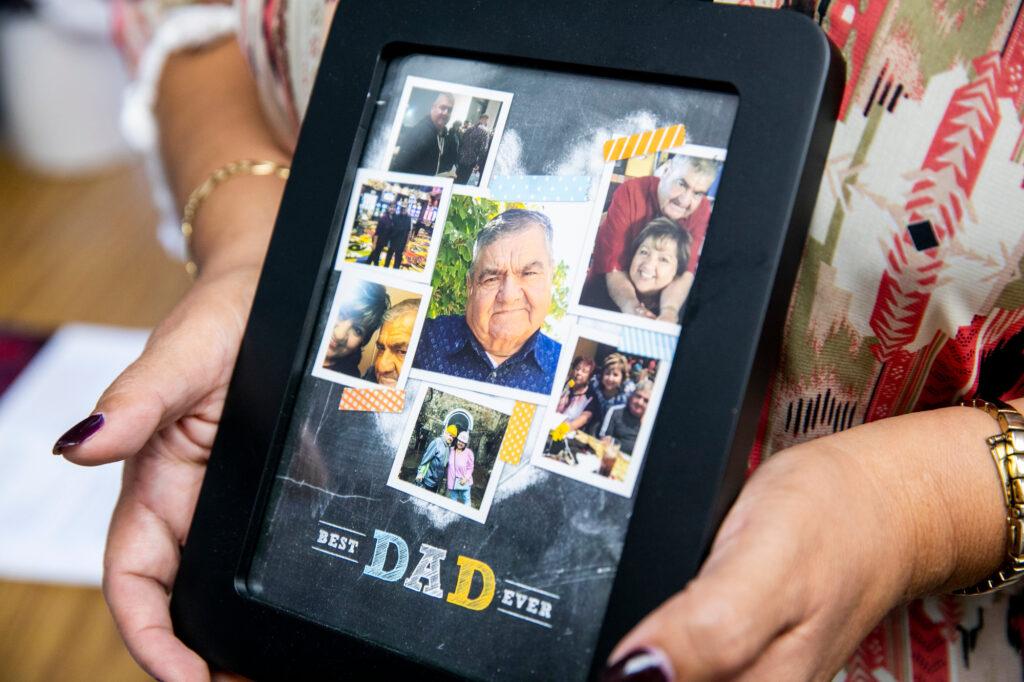

“He probably wasn’t even feeling better,” said Sanchez’s daughter, Beatriz Rangle, 53. "He just went to work because that's him. He's very responsible, very committed."

As he sliced meat on the line that day, the coronavirus was wreaking havoc on his lungs. Sanchez wound up in the hospital two days later and by the end of the week was put on a ventilator. He died on April 7.

Sanchez was just one of six of the plant’s workers who died of COVID-19 in the early days of the pandemic, among 291 JBS workers who were infected. But despite the well-documented incidence of COVID-19 within the plant, JBS has denied that some of the worker’s infections were work-related. Via a third-party claims administrator, the company has rejected the worker’s compensation claim from Sanchez’s widow and other JBS workers.

"The worker’s compensation claim denials were issued by our third-party claims administrator consistent with the Colorado Workers’ Compensation Act,” Nikki Richardson, a spokesperson for JBS said via email. In response to other questions she added, “We don’t comment on active legal proceedings."

At least three families are bringing their cases to court, according to lawyers contacted for this story. Money for medical bills, funeral costs and lost salaries are on the line in the cases, but for the families, the court challenge is also about seeking accountability for JBS.

"It's been a huge learning curve for our family and I never thought we'd be put in this position,” said Rangle, through tears, “But we don't want other people to suffer the same thing my dad did. That’s what my dad would have wanted us to do, to keep protecting the people he worked with.”

Accusations of negligence at JBS

Alfredo Hernandez, 55, started at the JBS plant around the same time Sanchez did. He worked as a janitor in the JBS cafeteria and had close contact with people from across the entire plant. In early March he started to hear about friends at work getting sick. He saw people with coughs or that seemed tired. He said that the company put bottles of hand sanitizer near the doors, but no one told them why.

“I have friends that got sick, but not really sick, and they kept coming to work,” he said in Spanish. “People were scared but they came because they had to. No one felt safe, but everyone has to work to take care of their family.”

After being diagnosed with COVID-19 Hernandez struggled to breathe. He’s lived with an oxygen tube since March and still struggles to walk without feeling faint. At night, he feels as though mosquitoes are biting his face, but no bugs ever appear in the bug zapper he had his wife put in their bedroom.

“I just feel scared any time I try to do anything,” he said in Spanish. “I don’t know, it’s like I’ve lost confidence in everything.”

Unable to work, Hernandez receives disability payments of about $750 a month, according to his wife, Rosario Hernandez. The money is barely enough to get by let alone cover the nearly $6,000 in medical bills that the couple’s insurance won’t cover. So far, JBS has denied Hernandez’s claims for worker’s compensation.

Even after Hernandez and Sanchez had gone to the hospital and when Colorado businesses were ordered to shutter under the March 25 stay-at-home order, other JBS employees kept going to work. Because the meatpacking plant was part of the food supply chain, it was deemed essential. Though the plant remained open in late March, by then it was becoming clear to public health officials that something was wrong at JBS.

According to a public health order released on April 10, Weld County hospitals and clinics registered 277 visits from JBS employees or their family members between March 1 and April 2. The order notes for comparison that in one of Greeley’s largest health care systems the average daily visits from JBS employees in February was two.

“The rapid nature of the spread of disease among JBS employees is very concerning, and the exponential spread of this disease across an employee population of several thousand would be devastating for both the employees and your company, and would quickly overwhelm the medical resources available in the hospitals and other health care providers in Greeley,” the order read.

That public health order was meant to close the JBS plant, but the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment reversed course the next day. Emails obtained by Columbia University through a records request indicate that pressure from the White House and the CDC prompted a shift at the health department to allow the meatpacking plant to stay open.

JBS wound up closing voluntarily for two weeks after COVID-19 tests revealed positive cases among managers. Despite promises to conduct tests on all of its workers, the company abruptly halted testing, according to representatives of the United Food & Commercial Workers union, which represents several thousand JBS workers.

Emailed questions to JBS regarding testing went unanswered. The plant does conduct routine surveillance tests on workers and the plant’s outbreak is now considered resolved, but the company’s handling of the outbreak has put it at odds with the union, which pushed for free on-site testing for all workers and the payment of worker’s compensation claims.

"As the virus spread, our members were labeled essential, but treated as disposable,” Kim Cordova, president of the local UFCW chapter, said in a statement. "The fact that even in death they continue to callously disregard their employees by denying their families workers’ compensation is a new level of cruelty."

In September, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined JBS $15,000 for failing to protect its workers from COVID-19, and new allegations of negligence surfaced last week from two temporary JBS employees. The two medical workers, Sarah-Jean Buck and Erica Villegas, were hired to help with screenings of employees during May and June.

In signed affidavits, the two alleged that from May to July JBS used screening equipment that was not functioning properly, allowed visibly sick employees into work and did not provide information for non-English speaking employees.

JBS has publicly opposed the OSHA fine and denied the allegations from the former workers.

“If they had just told us more at the beginning, they would have saved so many people. The people who died wouldn’t have died,” Hernandez said. “If they had just said stay home or something … but they just wanted people to come to work. They didn’t care if someone got sick, or someone died. They didn’t care about any of that.”

The burden on Colorado workers

The workers compensation denials for the Sanchez and Hernandez families show the difficulty that Colorado families face when claiming pandemic compensation. In Colorado, workers have to prove they were injured or sickened at work to claim compensation. This is difficult with a virus because transmission is not always easy to pinpoint.

“We are in unprecedented times,” said Paul Tauriello, the director of the worker’s compensation program at the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment. "We can look back in time as to how to deal with this. But we have a limit to the amount of authority that we have and the expectation of statute for us to intervene on this is quite limited.”

Since the start of the pandemic, the state has received 2,468 non-fatal claims related to COVID-19, about 67 percent of which have been denied. Of the 20 fatal claims to reach the department, only one has been admitted.

According to Tauriello, this is a very high number of rejected claims and are likely only a fraction of the total number of worker’s compensation claims related to the pandemic. The state only sees claims where the worker was permanently impaired or was forced to miss at least three days of work.

A bill that would have instructed insurers to assume that essential workers seeking compensation for contracting COVID-19 got sick at work failed in the legislature. The bill would have made it easier to get worker’s compensation for COVID-19, but families who have been denied still have a chance at having their claims admitted by the courts.

According to Tauriello, the state’s first pandemic compensation cases are just starting to get hearings. The results of those cases will be the true test of what workers can expect going forward.

Lawyers for both the Sanchez and Hernandez families are confident they can convince a court that their clients contracted COVID-19 at work. In March when the workers were sickened, the incidence of COVID-19 at JBS was higher than in the wider community. No other members of the Sanchez or Hernandez families got sick.

Both families are waiting for their hearings to be scheduled, and in the meantime have been speaking out as much as possible about what they see as injustice at JBS. Since coming out with their family’s story, Rangle’s phone constantly buzzes with messages from other JBS workers or their families. She says many families have been afraid to speak out for fear of losing their jobs or retaliation against other family members that work at the plant.

“We’ve been asked to speak for a lot of people,” Rangle said, while flipping through text messages from other JBS families on her phone. “They’re scared so we need to speak up and say what is going on."