The paths to U.S. citizenship are various, but each leads to this oath at a naturalization ceremony.

"I hereby declare, on oath, that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen; that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law; and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God."

Immigration has risen steeply in recent decades. More than 40 million people who live in the United States were born outside its borders, and nearly half of those folks are naturalized citizens.

Despite political polarization and the pandemic, thousands of immigrants continue to raise their hands and swear “true faith and allegiance” to the United States of America.

For more than a year, CPR News has been photographing new Americans as they take the Oath of Allegiance, and they shared their stories of what it is like to become citizens now.

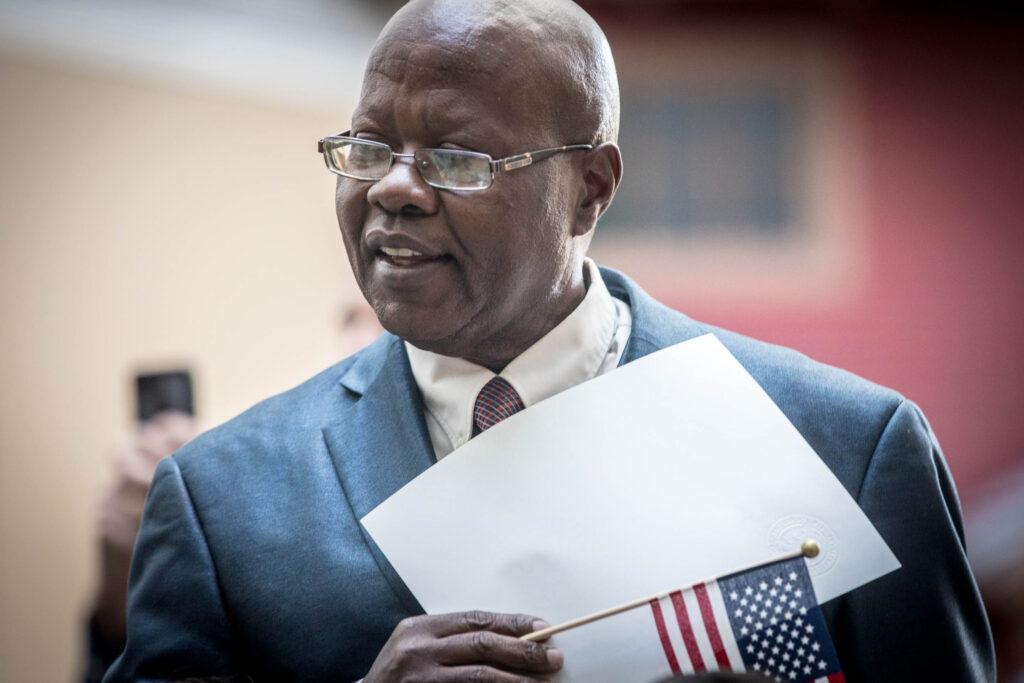

Jane Muriithi, her husband James and son Ian at History Colorado in Denver, Oct. 9, 2019

Jane Muriithi and her husband James moved to the United States looking for opportunities they weren’t finding in Kenya. James wanted higher education, and Jane wanted a better paying job and more education and career options for her children. From the beginning, they knew they wanted to become citizens.

“That was one of the goals,” said James, “because that was the only way to access the opportunities and identify with the American dream, including education, better job opportunities… the right to vote.”

When the family immigrated in 2009, James worked for the Kenya Mission to the United Nations. It took 10 years for the family to receive permanent resident status and then citizenship. In that time, James completed his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice, and he’s now pursuing his master’s in homeland security. Muriithi is working at Walmart, and their three children are grown and pursuing their own careers and education.

James says he gives advice to other immigrants: "Live within the four corners of the law. Pursue education. Work hard, and pay your taxes."

Jane adds, “You have to be yourself wherever you are. Respect each other.”

They also see voting as citizens’ responsibility, and they say that they are weighing candidates’ policies for dealing with the pandemic as they make their decisions.

"America being a nation which values governance and democracy… it was important to get that responsibility to vote,” said James. “ We are looking forward to casting a ballot."

Mike and Kirsten Le Roux at Brown Elementary School on Nov. 15, 2019

When Mike and Kirsten Le Roux and became citizens last fall, it was actually their second time to swap their passport. They grew up in South Africa, met and married in college, and moved to Australia in 1999, where they became citizens. When Le Roux’s athletic career took them to the United States in 2013, they knew that they wanted to change their citizenship again.

“I'm always of the opinion that, you know, when in Rome be a Roman, and if you want to have a say in the community and the future of your wellbeing, you need to embrace the culture,” said Le Roux. “You want to have a say in how things are run? You need to become a citizen.”

Le Roux, who is 44, came to the U.S. on a visa for professional athletes. He competed in ultra-endurance events, races longer than an Iron Man or marathon, and the U.S. offered more opportunities for racing and coaching than Australia. He and his wife became permanent residents 18 months after they moved. Then, after holding green cards for five years, they applied for citizenship.

“I couldn't have been happier with the processing time that we had. We couldn't have done it any quicker,” said Le Roux. “ I know that for others, that's been maybe slightly drawn out depending on the route that you choose.”

He said he’s also been happy with the move. A fellow racer recommended Pagosa Springs for its altitude, relatively mild weather, and open spaces -- all good for training. Le Roux said he and his wife are immersed in the community there, even though he’s slowed down on racing and taken another career path. He’s become the director of emergency operations for the Archuleta County Sheriff's Office, where he deals with natural and human-caused disasters in southwest Colorado.

Working in the sheriff’s office, which is an elected position, Le Roux says that he’s involved in politics at the local level. He’s worked on campaigns in the past, and he’s looking forward to casting his own ballot for Republican candidates, including President Donald Trump, in November.

He acknowledges that, “the political climate at the moment here is tumultuous.” However, when he compares U.S. politics to those he grew up with in South Africa, he says,“I don't see it being that bad here. Yes, there are differences, but ultimately everybody's free. Everybody's got opportunity.”

Whatever the outcome on Election Day, he says, “I'm not upset either way. We'll make it work. Life goes on. It's a great country, and we love it.”

Melva Herrera at Colorado National Monument, Sept. 16, 2020

Melva Herrera was in high school when she asked her parents for her social security card so she could apply for colleges and student loans. She didn’t have one.

“And me being kind of unaware growing up, it hit me that like, 'Oh, I'm undocumented.’”

She remembers her parents explained, “There just haven’t been any opportunities in terms of a pathway for citizenship.”

Herrera’s parents brought her to California from Mexico when she was nine months old so that her father would have better work opportunities. Like many people brought to the United States as children without documentation, she didn’t have an option to become a citizen and remain in the U.S.

When people ask her why she didn’t return to Mexico to apply for a visa to come back to the United States, she says, “The United States is all I've ever known. If I were to go back -- you always hear about people being punished and having to stay there for years, and then they apply, and then they still get rejected.”

Herrera struggled after high school.

“Instead of looking to go to even a community college, I just went the route of trying to find somewhere I could work,” said Herrera. “I did that for a number of years, just kind of working and kind of just not being able to grow within that company because I didn't have any sort of visa or citizenship. So it was a little frustrating, and I'd get a little depressed from time to time”

In 2011, Herrera married her husband, an American citizen. That meant her husband could petition for her to receive permanent residence. But she still had to go back to Mexico.

In January 2016, she traveled across the border for the first time since she was an infant.

"So as President Trump was being inaugurated into office, I was in Ciudad Juarez, waiting to find out if I was being accepted for my visa. So that was a little scary being out there on the other side of the border, the unknown -- whether I can come back or not."

She received her green card, and in 2019 she applied for citizenship.

“At the ceremony, one of the words that stuck out to me is they found us ‘eligible’ to be here in this country,” said Herrera. “I'm one of those people who are eligible, who are being allowed to be here and to live here and to have these rights. Whereas, I’ve been here all my life.”

She says she felt like she’s been in a separate community from people who are citizens. Now she’s excited to grow into new opportunities and to vote. She says she’ll cast her ballot for former Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Kamala Harris.

“People just have no idea that the laws in terms of immigration are just very challenging…. Now my goal is to get that house, to have that American dream, as everyone says, get that nice car and that job and just be happy.”

Phanvichka Rath Fisk at the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services in Centennial, July 31, 2020

As he entered his freshman year at The King’s College in New York City in 2004, Phanvichka Rath Fisk intended to get his degree and return to Cambodia.

He grew up in the capital city, Phnom Penh in the 1980s during years of continuing instability. Fisk said starvation was a constant threat.

“You constantly have to figure out ways to hustle and find something to eat.” He explained that at a young age, “you expect to go out and kind of make your own way in the world, so that you don't burden your family.”

He got a scholarship to attend The King’s College, and planned to be in the United States for four years to finish his degree.

“There’s a lot more that I can do, going back to Cambodia, create a path for other people, the kids in the neighborhood I was from… give them the idea that there are possible options,” Fisk said.

But when he got to New York City, he found a familiar face in his classes, a young woman he’d met on vacation in Southeast Asia. He can’t remember if that was in Thailand or Malaysia, but he remembers that he thought she was “kind of cool.”

They became friends, dated, and got married in a year.

“Once we got married, it was easier for me to find more work if I had a permanent residency. So because I married an American citizen, it was easy for me,” said Fisk. “But at the same time, I’m still holding onto the idea that maybe I should move back to Cambodia at some point. So that's the reason why it took me forever to apply for a U.S. citizenship because I've had the green card for over 10 years.”

This year was a turning point for Fisk, who now lives in Longmont. He said he’s grown jaded about American politics because he sees politicians “flip-flopping back and forth whenever it is convenient for them.” But a mentor convinced him that it’s his responsibility to vote.

Fisk said his friend told him, “‘Politics is always going to be messy, but that’s the whole reason why our country is great -- because we all have a role in it… and if you’re not playing your part, then it’s kind of hard for you to really have an opinion about it because you can’t change it unless you’re in it.”

They had that conversation in March, and Fisk took the Oath of Allegiance in July.

He hasn’t decided yet who he’ll vote for, but he said, “Regardless of the outcome, come November, I will be able to tell myself I can live with it. I did my part.”

As he’s thinking through how to mark his ballot, Fisk says he’s looking for candidates with “proactive” approaches to climate change, wildfires, and job creation.

More scenes from Brown Elementary on Oct. 10, 2019

Scenes from Friends School in Boulder, Feb. 13, 2020

More scenes from U.S. Citizens and Immigration Services, Centennial, July 31, 2020

More scenes from Colorado National Monument on Sept. 16, 2020