After throwing off Spain’s colonial hold in the 1800s and surviving a brutal revolution in the 1910s, the beginnings of a new national identity in Mexico slowly began to take root.

Decades after the dust settled, creatives, intellectuals and business leaders introduced new ideas and images from Mexico — and put them on the world stage. Industry flourished, the Mexico City-based movie business boomed and ushered in what would be known as the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema.

During this thriving era, a power couple, muralist Diego Rivera and painter Frida Kahlo, held court with fellow artists, politicians and famous faces. The influence of their art — and the art movement they were a part of — continues to fascinate viewers today.

This is the backdrop running through the Denver Art Museum’s new expansive look at Mexican Modernism, which opened Oct. 25. Using Kahlo and Rivera’s lives and works as a guide, their new exhibit “Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism” widens the scope of the movement beyond its two most famous names.

Becky Hart, the Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the museum, said the pull of Frida and Diego allows the museum to tell the stories of other Mexican artists working at the same time.

“That's how we introduce the other artists, as people who either collaborated with them or were friends and might've come to concerts or conversations at Casa Azul, Frida's home in Coyoacán,” Hart said.

One of the core ideas of the show follows the formation of a national Mexican identity through art. Both Kahlo and Rivera incorporate indigenous imagery and aesthetics into their works, and in the case of Kahlo, traditional outfits into her wardrobe — a few reproductions of which also accompany the exhibit’s 20 Kahlo’s paintings and drawings and 13 of Rivera’s paintings. Some of the works on display are accompanied by cultural artifacts that inspired the artists, like a stone Olmec next to a playful photo of Kahlo holding a similar statue.

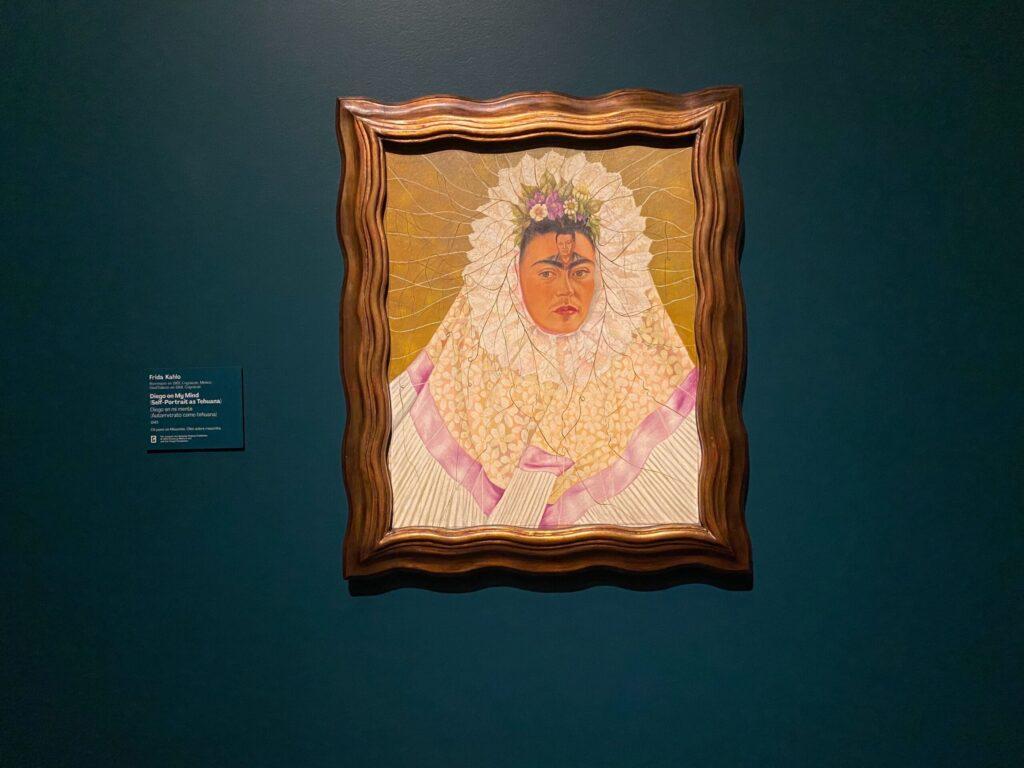

Although the exhibit opens with the somber tones of Rivera’s “Calla Lilly Vendor,” (Vendedora de Alcatraces) the works and space soon grow brighter with colorful walls displaying equally vivid works of art. On the other end of the exhibition, Kahlo’s self-portrait “Diego on My Mind” closes out the show with one last look at everything laid out before it.

In the portrait, she wears traditional indigenous clothing, but the tendrils of its fabric seem to sprout out from her headdress onto the edges of the frame. She is rooted here, but her mind is elsewhere, as illustrated by a reflection of her husband on her forehead.

“What we realize is that we're telling a story that's very complex and very layered,” Hart said. “There can be multiple realities that can sit side by side, sometimes in harmony and sometimes in contradiction. But part of the uniqueness of Mexican heritage is that all is embraced. Death is embraced as part of life. Joy is embraced as part of sorrow.”

Kahlo and Rivera were far from the only artists grappling with the question of identity, patriotism, tradition and progress. Among the works from their contemporaries in the exhibit include María Izquierdo’s “Naturaleza viva,” a still life study of Mexico’s land and sea bounty, and Carlos Mérida’s “Festival of the Birds,” an abstract celebration of shapes.

The examples also show off the variety of styles from Mexican artists at the time, as Gunther Gerzso and Mérida’s geometric paintings lean further into the abstract than Izquierdo’s colorful works and Lola Álvarez Bravo’s stark black-and-white photography.

In addition to the artists, among the couple’s friends were art collectors Jacques and Natasha Gelman. Jacques, a movie producer who made his fortune working with Mexican actor and movie producer Cantinflas, and his wife Natasha collected the works of their friends like Kahlo and Rivera and their image appears in some of the artwork in the show, which features many pieces from their namesake collection.

The conversation about cultural identity is also woven into the fabric of the exhibit’s layout and design.

“We worked with Mexican designers who did the spatial and the experiential design, as well as the graphic design for the exhibition,” Hart said. “They wanted to be very precise about how we did the history, so they hired a historian in Mexico city to work with us.”

The crowds that flocked to the Denver Art Museum’s popular Claude Monet exhibit last year will have to experience the Mexican Modernists exhibit in a different way than the curators originally planned.

Some adjustments had to be made for social distancing guidelines because of COVID-19: Visitors must buy timed tickets to avoid crowding and the museum added hand sanitizing stations throughout the space. The museum will have to make adjustments yet again as new state-mandated ordinances for the city will now require the institution to drop capacity.