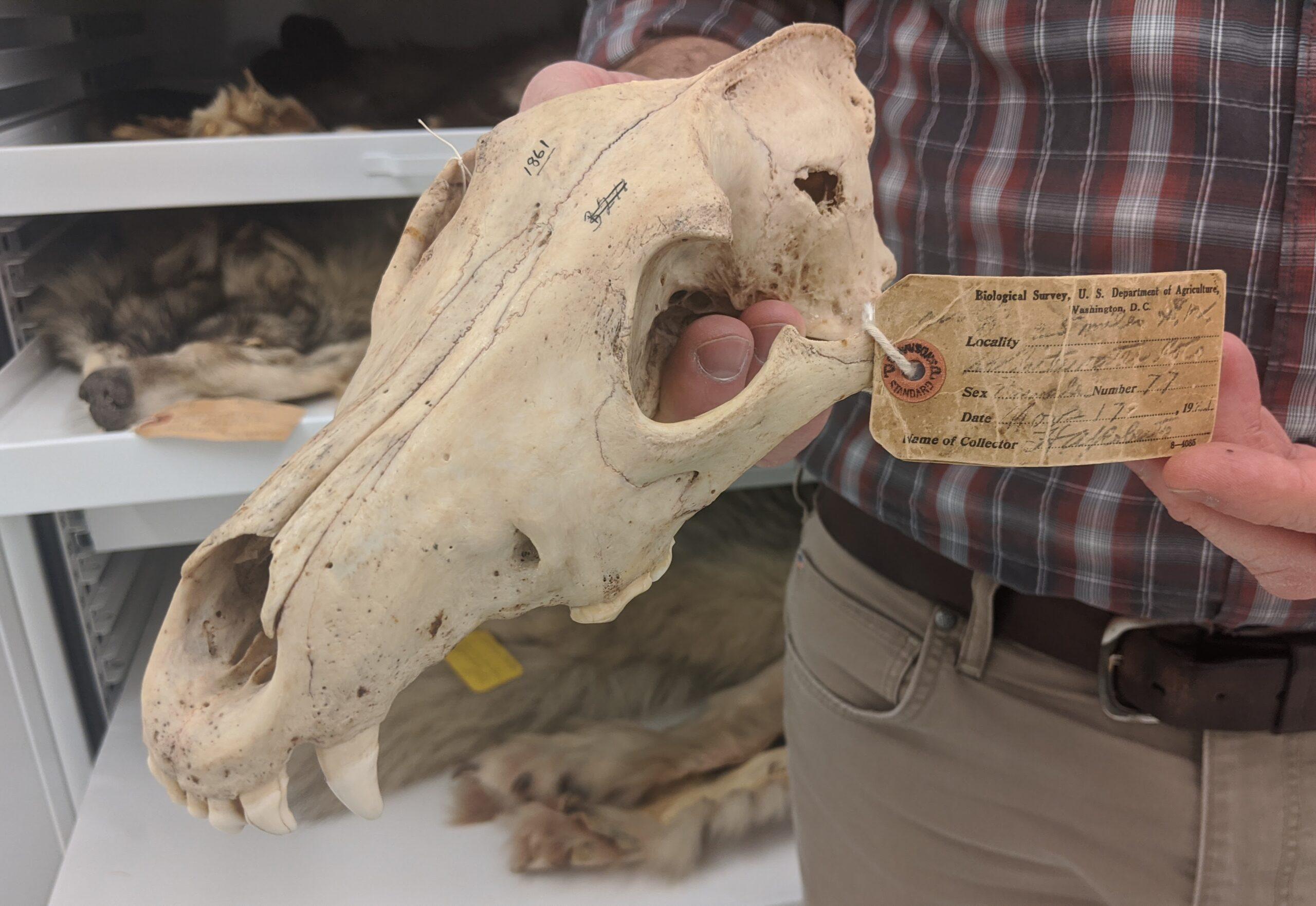

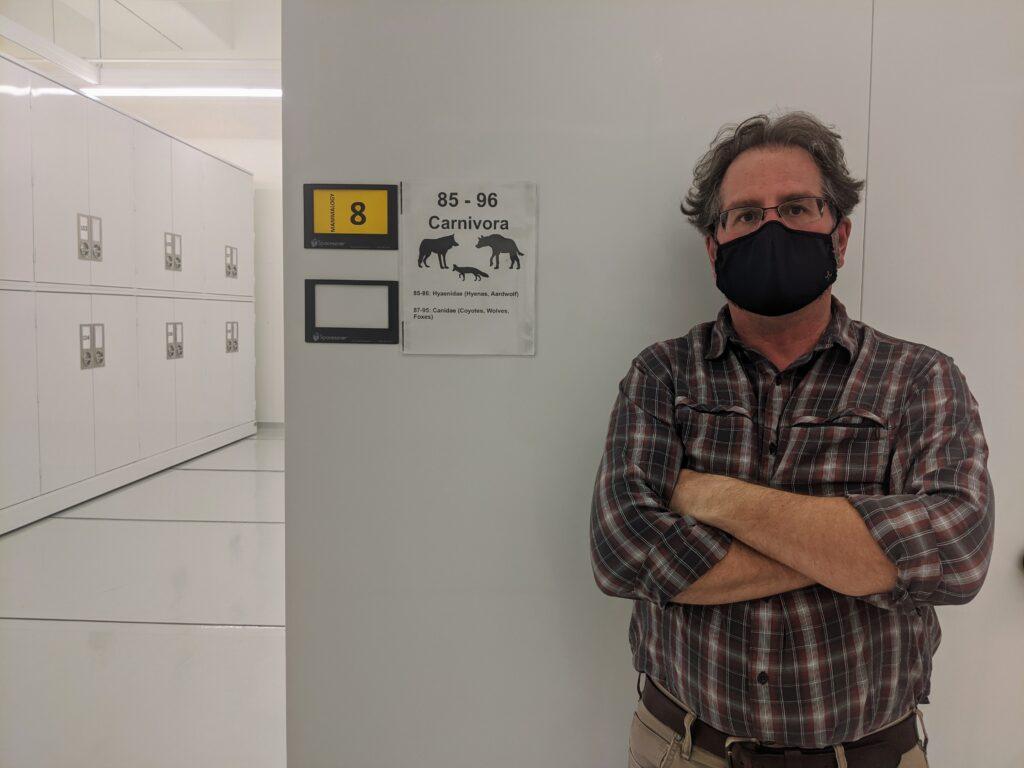

On a recent afternoon, John Demboski opened up a tall white cabinet in the Denver Museum of Nature and Science basement. Reaching to a top shelf, the zoology and mammals curator pulled out a wolf skull with a yellowed tag attached.

Faint scrawls of pencil reveal the animal’s fate. Trappers killed the wolf in 1917 outside Grand Junction, Colo., as a part of a federal program to eradicate the predators. Demboski then points out a pair of gaps across the top of the skull.

“That’s the bullet hole, right there,” he said.

While Colorado’s original wolves were eradicated in the early 20th century, their memory has taken on new life ahead of the 2020 election. On Nov. 3, voters will consider Proposition 114, which asks whether the state should restore the predators to the Western Slope by 2024.

Hunters and ranchers have led the campaign against the initiative. Rethink Wolves, the main political group against reintroduction, has focused on the threat wolves present to wildlife, livestock and the resources of Colorado’s state wildlife agency. A less organized contingent of opponents has gone further, claiming Colorado’s future wolves would be more than a menace; they’d be a “non-native species.”

Greg Walcher, who directed the state Department of Natural Resources under Republican Gov. Bill Owens before becoming a political consultant, laid out the argument in a video interview with the Independence Institute, a free-market think tank based in Denver.

“This is not a reintroduction. It’s an introduction of a species that is not native to Colorado,” said Walcher in the video. “The species of wolves that was native to Colorado is a species of timber wolves that is extinct now.”

‘A gray wolf is a gray wolf’

The objection is a direct descendant of the debate over wolves in Yellowstone National Park. In the 1990s, the federal government released wolves from Alberta in the park and central Idaho to restart a population in the northern Rockies. As the wolves multiplied, so did the claims the new arrivals were a breed of Canadian “super wolf” far larger than what had originally prowled the lower 48 states.

The National Park Service even made a video addressing the topic. In it, Doug Smith, the NPS’s lead wolf biologist, explains the park’s historic wolves were slightly smaller than the reintroduced predators but were likely just as big in some instances.

If voters approve the initiative, the offspring of Yellowstone’s newer wolves might be brought to Colorado. The ballot language leaves the final decision to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission, which would develop a plan for reintroduction with public input.

Mike Phillips, a Montana state senator and wolf expert who’s backing the initiative, said he would recommend the state reintroduce wolves from Montana since those animals have experience hunting elk in a Rocky Mountain landscape. The Colorado commission could also decide to capture and release timberwolves from the upper Midwest.

“You could go to Minnesota and get deer-killers,” he said.

Either way, Phillips said Colorado wouldn’t be introducing a non-native “species” since gray wolves are classified as just one species, both in biology textbooks and under the Endangered Species Act: Canis lupus, if you want to get Latin about it.

“It doesn’t matter. A gray wolf is a gray wolf is a gray wolf,” he said.

Walcher, the political consultant, clarified he never meant to claim Colorado’s original wolves were a separate, extinct species from the gray wolves still alive today. Instead, he thinks they are part of an extinct subspecies, but he says “species” just because “a lot of people don’t know the difference.”

Whether or not Colorado’s original wolves belong to an extinct subspecies depends on the messy world of wolf taxonomy. Kevin Crooks, a wildlife ecologist at Colorado State University, explained scientists once identified 24 subspecies of the gray wolf in North America. Today, most scientists recognize only five categories since wolves travel so far and interbreed so much.

Under the earlier classification, the original wolves in western Colorado were southern Rocky Mountain wolves, which are now considered extinct. Under the new classification, the animals are Great Plains wolves, which remain alive today in the upper Midwest. Crooks said he doesn’t put too much stock in the distinction — and doesn’t think voters should either.

“Ultimately, the difference between most wolf subspecies is not substantial,” he said. “Wolves were distributed through most of North America, can travel long distances, and there was almost certainly interbreeding between wolf subspecies.”

Hunters and predators

But taxonomic debates aren’t much comfort to rancher Brad Hart, who raises cattle near Crawford, Colo. As an avid hunter, he still worries the ballot initiative could bring a larger variety of wolves than what once lived in Colorado — with a bigger appetite for the elk and deer he’d like to hunt himself.

“I have a concern that they are introducing a larger breed of wolves here than our game animals can deal with,” he said.

John Demboski, the curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, said archives lack enough samples of Colorado’s original wolves to substantiate a claim about their typical size. There is a clear trend within the species, though. In most cases, larger wolves live to the north of their smaller cousins. That said, he’s also not sure the exact dimensions of Colorado’s first wolves matters.

“What the size translates to, meaning in terms of its biology or the prey — that’s a different story,” he said.

Some of the wolves in his collection are quite large, though. The tag attached to one of the skulls suggests it belonged to the Unaweep wolf, which earned a reputation for killing livestock and evading hunters in the 1910s. Accounts claim it weighed 110 pounds and was as tall as a small Great Dane. If true, that would put the wolf well within the range of the wolves currently living near Yellowstone.

Meanwhile, reintroduction advocates say the goal was never to revive museum artifacts. The real point, according to Phillips, is to return predators capable of the same basic job as Colorado’s original wolves.

“When you think about extinction, we’re not only losing species; we’re losing ecological processes,” he said.

Phillips said prowling wolves shaped Colorado’s ecosystem for millennia, affecting other species’ evolution and supporting biodiversity. Even if Colorado one day reintroduces wolves that are slightly different than its originals, he said the animals could still fill a gap that was left behind.