Updated 7:37 a.m.

Kurt Papenfus, a doctor in the small town of Cheyenne Wells, started to feel sick around Halloween. He developed a scary cough, diarrhea and a headache.

In the midst of a pandemic, the news that he had COVID-19 wasn’t surprising, but Papenfus’ illness would have repercussions far beyond his health.

Papenfus is the lone full-time emergency room doc in the town of 900, not far from the Kansas line.

“I'm chief of staff and medical director of everything at Keefe Memorial Hospital currently in Cheyenne County, Colorado,” he said.

Just 16 people in the county have been diagnosed with COVID-19.

With him sick, the hospital scrambled to find a replacement and would have to divert emergency patients elsewhere. As of now, a hospital official says they have coverage of the doctor's hours through Nov. 28.

As coronavirus cases in rural Colorado, and the eastern plains especially, surge to unprecedented levels, Papenfus’ illness is a test case for how the pandemic could impact the fragile rural health care system.

“He is the main guy. And it is a very large challenge,” said Stella Worley, CEO of the hospital.

If she can’t find someone to fill in while he’s sick, she may have to divert trauma and emergency patients nearly 40 miles south to Burlington.

“Time is life sometimes,” she said. “And that is not something you ever want to do.”

'The 'rona beast is a very nasty beast'

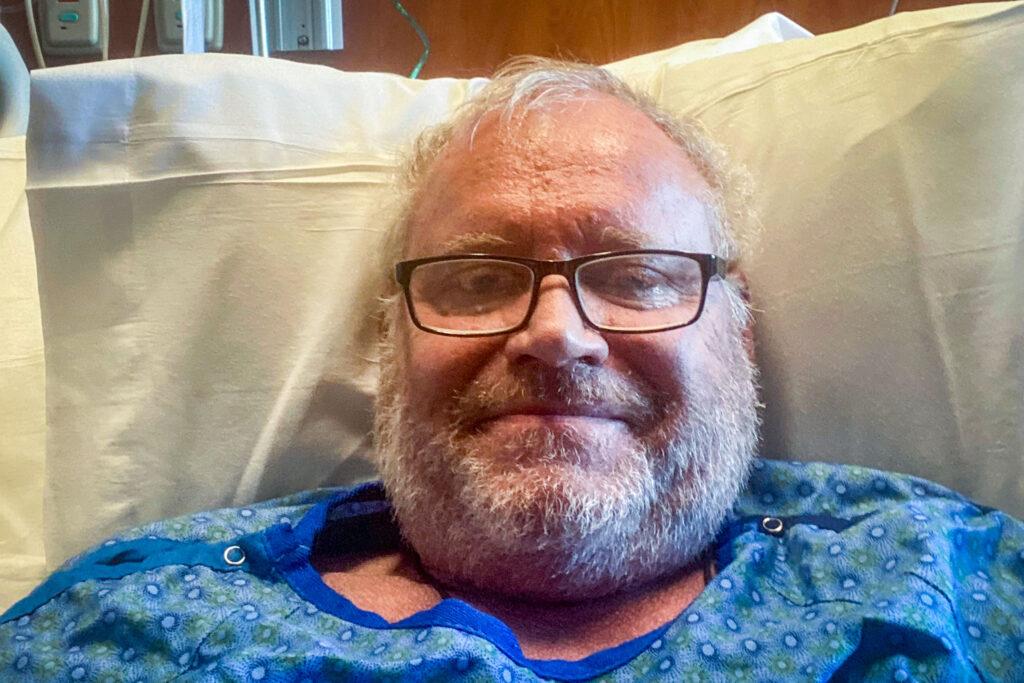

Papenfus, a lively 63-year-old now installed in a hospital bed in St. Joseph’s in Denver, is eager to sound the alarm about the disease he calls “the ‘rona.”

“The ‘rona beast is a very nasty beast and it is not fun. It has a very mean temper. It loves a fight and it loves to keep coming after you,” he said.

He isn’t sure where he picked it up but thinks it might have been a trip east in October. He says he was meticulous on the plane, sitting in the front, last on, first off. But on landing at DIA, Papenfus boarded the crowded train to the terminal and soon alarm bells went off in his head.

“There are people literally like inches from me and we're all crammed like sardines in this train,” Papenfus said. “And I'm going, ‘Oh my God, I am in a super spreader event right now.’”

A week later, the symptoms hit. He tested positive and decided to drive himself the three hours to the hospital in Denver.

“I'm not going to let anybody get in this car with me and get COVID, because I don't want to give anybody the ‘rona,” he said.

County sheriff’s deputies followed his car to be sure he made it.

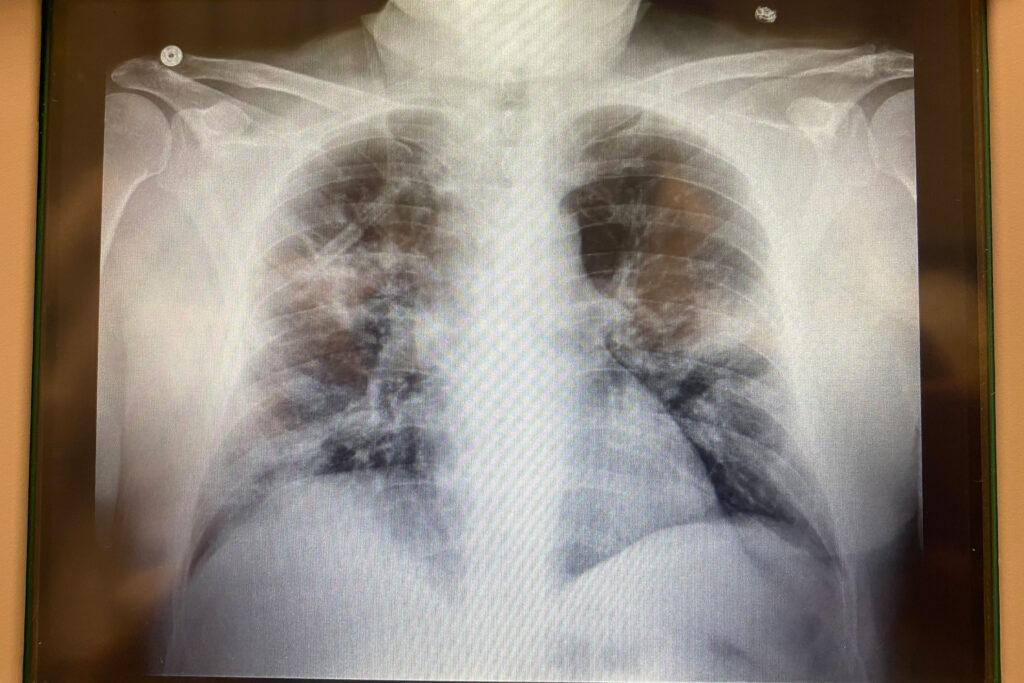

Once in the hospital, chest x-rays revealed he’d developed pneumonia.

“Dude, I didn’t get a tap on the shoulder by ‘rona, I got a big viral load,” he texted me, sending images of his chest scans that show large white areas of his lung.

Just a week ago, his chest X-ray was normal, he said.

Back in Cheyenne Wells, Dr. Christine Connolly picked up some of Papenfus’ shifts, although she has to drive 10 hours each way from Fort Worth to do it. She says the hospital staff is spread thin already.

“It's not just the doctors, it's the nurses, you know. It's hard to get spare nurses,” she said. “There's not a lot of spares of anything out that far.”

Besides Papenfus, another two employees, out of a staff of 62 at Keefe Memorial Hospital, had also recently gotten a positive test, Worley said.

Papenfus' sickness affects many beyond him

Hospitals on the plains often send their sickest patients to bigger hospitals, in Denver and Colorado Springs. But with so many people around the region getting sick, Connolly is getting worried hospitals could be overwhelmed. Health care leaders created a new command system to transfer patients around the state to make more room, but Connolly says there is a limit.

“It's dangerous when the hospitals in the cities fill up, and when it becomes a problem for us to send out,” she said.

The impact of Papenfus’ absence stretches across the Eastern Plains. He usually worked shifts an hour to the northwest, at Lincoln Community Hospital in Hugo. Its CEO, Kevin Stansbury, says the spring surge mostly left Hugo alone. The facility took in recovering COVID-19 patients from the city.

Now Stansbury said the virus is reaching places like Lincoln County, population 4,000. It has had 41 cases according to state data, but neighboring Kit Carson has had 213 and Crowley to the south has had 245. Those rates put them in the top 10 most affected counties per capita.

“So those numbers are huge,” Stansbury said. He said about a half dozen staffers also tested positive for the virus; they think it’s unrelated to Papenfus’ case.

The hospital is ready to once again take recovering patients. Finances in rural health care are always tight and accepting new patients would help.

“We have the staff to do that, so long as my staff doesn't get ravaged with the disease,” Stansbury said.

Rural Colorado is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19

Residents tend to suffer from health conditions that make people vulnerable to COVID-19, with relatively high rates of cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, and obesity. And Brock Slabach, with the National Rural Health Association, said 61 percent of rural hospitals do not have an intensive care unit.

“This is an unprecedented situation that we find ourselves in right now,” he said. “I don't think that in our lifetimes we've seen anything like what is developing in terms of surge capacity.”

A couple of hours east of Cheyenne Wells, COVID-19 recently hit Gove County, Kansas, hard.

The county’s emergency management director, the local hospital CEO and more than 50 medical staff tested positive. In a nursing home there, most of the more than 30 residents caught the virus; six died since late September, according to the Associated Press. A county sheriff ended up in a hospital more than an hour from home, fighting to breathe, due to the lack of space at the local medical center.

From his hospital bed in Denver, Papenfus frets about his home county and their odds of fighting off the virus.

“The western prairie isn’t mask country. People don't wear masks out there; bank robbers wear masks out there,” he said.

He’s not sure when he’ll be able to return to doctoring. On Tuesday, he said he hoped to be released soon. But on Wednesday Papenfus texted that he’d developed “secondary pneumonia big time!! They’re carpet bombing me with powerful antibiotics. Saved my life.”

Papenfus is urging Coloradans to stay vigilant, calling the virus an existential threat.

“It’s a huge wake-up call,” he said.