This is a continuing series on one of the first classrooms to go back to in-person learning – Renea Sutton’s Level 3 classroom, Room 132, at Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy in Westminster Public Schools.

Teacher Renea Sutton walked back into her classroom on Oct. 30 to a room decorated in posters welcoming her back. After a month of family leave, it was a relief to be back in the classroom.

“We were all like, ‘Yay, Mrs. Sutton came back,’ there was like, ‘Welcome back Mrs. Sutton, welcome back!'” said 8-year-old Azriel, describing the posters that lined Room 132’s walls at Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy.

The kids made a scavenger hunt for her.

But that didn’t last. That very night the district announced it was going remote for two weeks.

“I was kind of scared because we only got to see Mrs. Sutton for three days,” said Kimberly, describing her reaction to the news they were going remote.

Right from the start of the pandemic, Westminster Public Schools, just a few miles northwest of Denver, was determined to keep classrooms open for children. They’ve been open since Aug. 20 for the two-thirds of the district’s 9,500 children who chose it.

But a few weeks ago, COVID cases in Adams County began to rise. Superintendent Pamela Swanson told the school board transmission rates within schools were low and she wanted to stay the course.

“We’ve been in school a whole quarter, we’ve developed relationships with kids, and I just have to tell you there’s a sparkle factor and a magic when you’re able to have kids in person,” she said. “Our students are safe and still learning.”

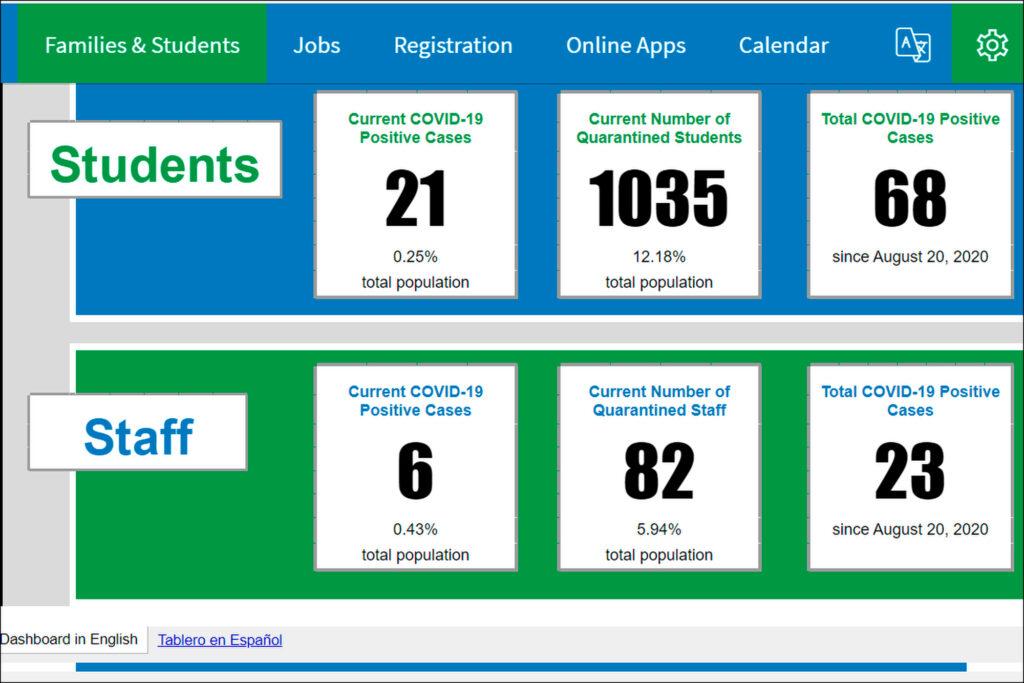

But soon, the district’s dashboard showed 12 percent of students were quarantined, there were three positive student cases at a middle school, and Adams County was on the state’s second-highest warning level. It was time to go remote.

Sutton’s students had a sour view of remote learning.

Balentina found out about the switch early, from her mom.

“I don’t like remoting because it’s just staring at the screen the whole time!” she said.

“When Balentina told me that I literally dragged my backpack all the way to the line [lineup line],” Amaya said.

But they’re trying to look at the bright side.

“If we don’t go remote we have a bigger chance of getting COVID,” said Jordynn, who lives with her grandmother.

“Plus we gotta wear this for eight hours if we stay here,” added Amaya, holding up her mask.

Still, the hiccups of remote learning quickly become clear.

On a Tuesday, just over a week into learning from home, the kids, wearing sports team shirts, looked tired — way more than they do in school. Some children were slurping up the last of their cereal. Most of them have an aunt or an older brother or sister or grandmother watching them. But some caregivers must work.

“My mom is leaving for work soon so I’m not going to be on the meeting for long,” 8-year-old Sebastian told Sutton right off the bat.

His mom popped on the screen and she says he can stay in class longer but she’ll be late for her job cleaning houses. Sutton reassured her and says that Sebastian can bring his laptop to do classwork. Another student, Monsi, explained she had to go to the store with her mom yesterday, but she handed in her work later.

“I understand, with your families, you have things going on,” Sutton told them. “I’m here to help you and work with you. We already agree this is not as good learning as it is if you were here [in school]. We learn so much more when we’re in school, but we also don’t want to have two weeks of no learning at all.”

The kids started the day in break-out rooms to discuss how remote learning is going.

“OK, Monsi you start, how is remote learning?” Amaya asked her classmate.

There’s a long pause while Monsi looks for the ‘unmute’ button.

“Bad obviously,” Monsi said dejectedly. “I hate it. Because every time I’m done with remote learning my eyes burn and they’re like red.”

Monsi’s a diligent student. She told Sutton later her eyes hurt so badly she had to use eye drops. Sutton encouraged her to step away and take breaks from the computer when she can. Amaya told her friends she likes remote better.

“I don’t like to be around people,” she said, in a teasing tone of voice.

These normally attentive kids find it so hard to focus online. The boys especially seem enamored with their images, putting their mouths up to the camera. One wandered around the house with his laptop, and another repeatedly taps the microphone. Loud breathing noises occasionally interrupted Sutton mid-sentence.

“Whoa careful guys,” she reminded them. “Do me a favor and mute yourselves until you’re going to talk because we can hear you breathing.”

Sutton juggles a lot during remote learning. A new student started the day they went remote and he doesn’t have the workbook yet. She manages to get him a digital copy.

Sutton has slimmed down what she normally teaches, focusing on math and literacy and social studies or science. Teachers have said it takes much longer to get through the same amount of material online compared to in-person.

Sutton said interaction with the students is especially difficult, but she has a few illuminating moments.

During their literacy class, they started with vocabulary. They’d read a story the day before about immigrating to the United States. Sutton asked what “immigrate” means.

Balentina, who is learning English, said it means getting used to that country. Alejandro expanded that, saying it’s “going from one country to another.”

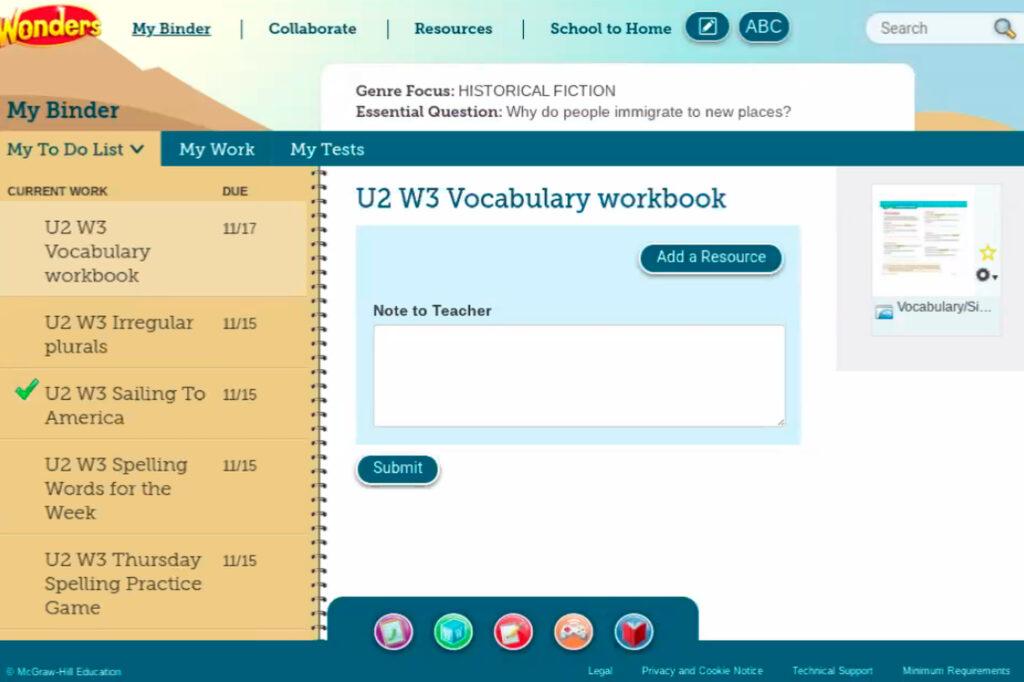

Then they break for a couple of hours to independently complete tons of assignments. They have Sutton’s Google number and can jump on Zoom at any time to ask a question.

At 12:30 p.m. when they regroup, the kids look more refreshed.

Sebastian, the boy who went to work with his mom, returned for the afternoon session. Sutton asked what they ate for lunch: corn dogs and a banana, tacos, eggs, three Kit Kats, four cups of water.

Then in math, the third graders take up the concept of distributive property, starting with a video. They talk about how you can find patterns on the multiplication table.

The kids each have heaps of online assignments organized in an online learning platform that they know how to access because Sutton uses it regularly at school. At the end of the lesson, Sutton flips to a page that shows her how many students have done their math homework.

“I only have eight out of 13 have finished,” she said. “There’s a lot of people who haven’t finished their work from last week. You need to go back in and finish these things. Just because we’re remote doesn’t mean I can skip through these things.”

Academics aside, the kids yearned for the connection of in-person learning. They say random things during the lessons and just share little bits of their lives. Amaya pointed out a bird on her balcony. Monsi raised her hand on the screen.

“Monsi, what’s your question hon?” asked Sutton.

“I just wanted to say a comment,” she said. “I’m excited because in seven days my baby sister is going to be four months. She almost wants to hold her own bottle.”

They chatted about that a while, but it’s not the same as in-person. Sutton usually circulates, looking her students in the eye; they feel her presence and she feels theirs.

One moment sticks out as an example of this time of distance learning: In one corner of Sutton’s screen, one of the students’ cameras just shows the boy’s raised fist, backlit. He was squiggling on the floor as class carried on. He has attention deficit problems and in-person, Sutton has really worked to give him strategies for staying focused. But here, alone in his room, trying to learn, all he can do sometimes is lie on the floor and shake his fist.

As of Friday, Westminster Public Schools is scheduled to return to in-person learning on Monday.

The district is going against the tide. Over the past two weeks, a growing crescendo of districts has rolled back to fully remote learning as the number of coronavirus cases in several counties shoots upward.

Neighboring district Adams 12 Five Star schools is moving its elementary students back to remote starting Monday. Its middle and high school students were already in remote learning. Denver moved its elementary students back to remote a week or so after bringing them all back into the classrooms.

Among the districts moving to remote are Cherry Creek, Aurora, Sheridan, and Littleton Public Schools, which just announced the district had “reached a tipping point in the system where in-person learning is no longer feasible.”

Districts say staffing and substitute shortages are getting worse due to quarantines, making it impossible to continue instruction in-person. Douglas County just made the call to shift preschool through 12th grade to remote learning after Thanksgiving and Jeffco made the decision to do so Thursday.

Beyond the metro area, Montezuma-Cortez and large districts Pueblo 60, Falcon School District 49 and Colorado Springs D-11 in the Pikes Peak Region also will be transitioning to remote learning.