In this pandemic, it seems no one wants to be the villain.

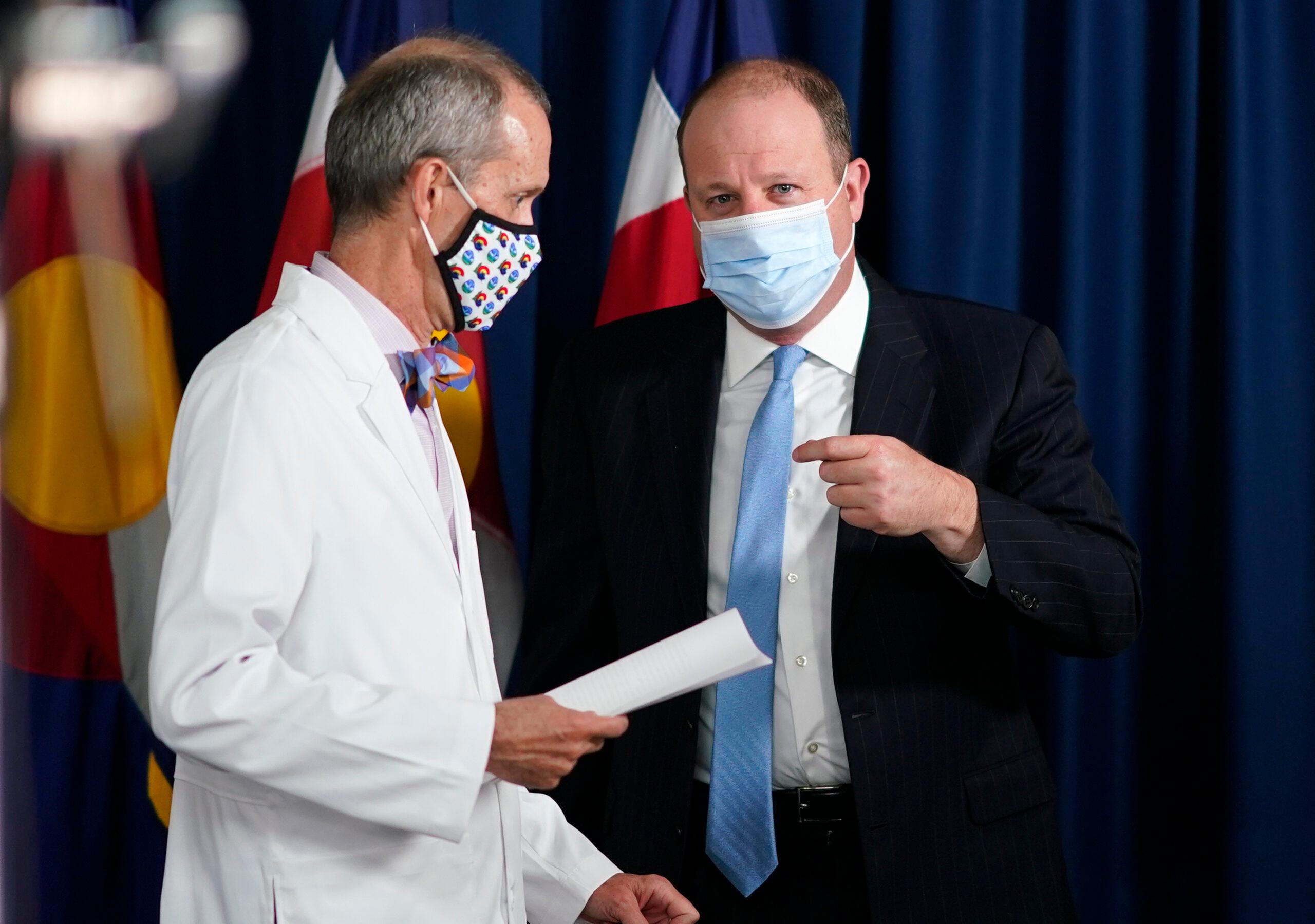

Not Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, who has resisted issuing a new lockdown order even as infections, hospitalizations and deaths rise to record or near-record levels.

Not state public health officials, who created a new half-step of restrictions rather than impose new “stay-at-home” orders.

And definitely not the leaders of local governments, whose own actions are under intense scrutiny, and who hear directly from voters anytime they advocate for tougher rules — or resist them.

The debate over who should be the bearer of bad news for businesses and residents has gone on throughout November as local public health directors implored Polis to get tough on the virus.

Now metro Denver mayors have written to the governor, complaining about a lack of communication from the state and saying they feel ill-equipped to explain to residents how decisions are being made.

“We are extremely concerned about the looming potential loss of life and the economic effects of another shutdown,” reads a letter to Polis from the Metro Mayors Caucus, dated Nov. 23. “We understand that we are all learning as we go, but nine months into this crisis, there is widespread agreement that we must improve communication and coordination.”

The mayors acknowledged the role of local governments in reducing the spread of COVID-19.

“However, to be a good partner to the state, we need a clearer understanding of the data that is driving decision making to ensure effective messaging,” reads the letter. “To this end, we would like to engage in a dialogue with your team and our public health directors as soon as possible to discuss our path forward.”

Cities and counties want more notice before the state moves them to more restrictions.

As counties have been shifted into tighter restrictions on the state’s “Covid-19 Dial,” local health departments have often blamed the state, while state officials have at times said compliance and enforcement are local responsibilities.

But now that the next step for every Front Range county from Pueblo to Larimer would be a stay-at-home order, the mayors want more warning for businesses and better overall communication.

“So with this last switch from orange to red, I think we had two or three days notice,” said Adam Paul, mayor of Lakewood in an interview. “And when you have restaurants that are ordering, making purchase orders or have parties, you have workers who have a day or two notice to say, ‘Hey, you're not going to have a job come tomorrow. You need to look for unemployment.’ It's challenging.”

Paul said the governor’s office has done a good job making staff available to the metro mayors.

“So I don't want to be critical in that regard,” Paul said. “The letter was signed by 26 mayors that represent over 2.2 million people in the region, and I think it’s just a needed check-in as we're going into potentially more shutdowns. And this could be even more devastating without any federal action [on a COVID-19 stimulus package].”

Lone Tree Mayor Jackie Millet said in an interview that she sympathizes with the tough situation state leaders are in, but it’s local governments that field a lot of the frustration from businesses about changing restrictions.

“And I think we at the local government level want to make sure that we understand where the state is going on this,” Millet said. “And that we don't hear [of new restrictions] from a press conference.”

The letter comes less than three weeks after county public health officials sent their own letter to the Polis administration asking the state to essentially push counties into stay-at-home if warranted. The state’s criteria indicated that the spread of COVID-19 in many counties meant they should be locked down.

Rather than impose a stay-at-home, the governor’s office and state health department created a new level, with restrictions on dining and other events, short of a stay-at-home.

In a statement Monday night, Polis's office said he is balancing public health and the economy in every decision he makes.

“The Governor knows that for our state to come out of this pandemic it will take all of us; people at home, local, state, and federal governments doing their part and that is why our office and the state health department have provided numerous briefings, modeling updates to local governments throughout this pandemic,” read the statement. “Each piece of policy is based on data and researched and balanced with as minimal impact on the state’s economy as possible.”

The confusing standoff over restrictions and enforcement is a byproduct of Colorado’s political structure, which allows local control over decision-making but also grants the governor broad powers in an emergency.

“I think it's also a reflection of the structural weaknesses of our public health system, de-centralized and pretty fragmented,” said Glen Mays, a professor at the Colorado School of Public Health. “In other circumstances, local public health relishes its decentralized decision-making capacity, but I think here locals are bearing the brunt of weaknesses in communication. And they're bearing the brunt of it in terms of a lack of a unified approach.”

“That can undermine understanding, and undermine public and private sector buy-in into the response activities,” Mays added.

Confusion as coronavirus cases and hospitalizations continue to rise in Colorado.

The state’s positive test rate, averaged over seven days, had been on the decline but has now risen for two consecutive days, back to more than 11 percent of all tests coming back positive.

Of greater concern is the number of people hospitalized with confirmed and suspected cases of COVID-19, which rose sharply on Nov. 30 to 1,940, an increase of nearly 100 patients in a day.

With hospital capacity — in beds and staff — a finite resource, Polis may soon have to consider opening overflow treatment centers around the state, which will take two weeks or more to prepare. For now, hospitals have been able to accommodate the additional caseload, but roughly one-in-three hospitals have regularly said they anticipate staff shortages within a week.

That puts pressure on hospitals up and down the Front Range, but the Metro Mayors Caucus letter singled out inconsistent enforcement of public health orders by the state, in particular in Weld County.

“There is broad agreement that the state must evenly apply and consistently enforce public health orders,” according to the letter.

Back in July, after Polis issued a statewide mask mandate, Weld County was quick to respond: “The Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment will not enforce Gov. Polis’ executive order, which has no legal effect, requiring residents to wear non-medical face coverings indoors,” according to a statement from the county commissioners.

Weld County has also hosted events that far exceed capacity limits, and were not allowed by other counties.

“You might have some folks in Adams County, business owners, that aren’t able to be open, but yet their residents can just drive to Weld and take part in those different services,” Lakewood Mayor Adam Paul said.

With news that several vaccines appear to be effective against COVID-19, “there's an end somewhat in sight. If we can hold it all together, as painful as it is, we'll be better off,” he said.

A day after the metro mayors sent their letter to Polis, on Nov. 24, The Longmont Times-Call reported that Longmont city leadership directed staff to draft an ordinance, taking aim at Weld County, that would make it illegal for the city’s hospitals “to provide medical services to any resident of a county or municipality wherein their elected officials have refused to comply with the governor’s emergency orders...”

The next day Longmont reversed course and dropped the proposed ordinance.

Who owns coronavirus enforcement?

Still, tensions between local governments and the inherent political problem of passing restrictions haphazardly from county to county have locals asking the governor for help.

And where there are clear restrictions, the mayors want consistent enforcement of the public health orders.

“For example,” reads the mayor’s letter, “restaurants that refuse to close should face suspension and/or revocation of state licenses. Additionally, local governments that refuse to enforce public health orders should not receive state aid or any share of state funding normally allocated.”

“Willful non-compliance jeopardizes the lives of their residents and those in neighboring counties,” reads the letter.

The state has the authority to seek suspension of licenses for businesses that violate health orders but has largely chosen to leave enforcement to local governments or to focus on education of business owners in violation.

When a Castle Rock coffee shop was seen on social media in May with customers filling the restaurant in defiance of a state order, Polis moved swiftly to suspend their license. That briefly shut down the restaurant, but also triggered protests across the state and contributed to a publicly-declared effort to recall Polis that never got off the ground.

Since then, the state has appeared reluctant to get involved in local rebellions.

“It does very much affect our credibility when other jurisdictions openly flout that guidance, and there appears to be no consequence,” Lone Tree Mayor Jackie Millet said. “I've had a restaurant owner call me to say ‘my buddy up in such and such a county is open. He's open for business, mayor, why can't I be open for business?’”

The pointed statement from Polis' office said he too was frustrated with local governments that refuse to enforce public health orders.

“We share the group’s disapproval of the misguided efforts of very few local governments to undermine — with no real authority — the state’s efforts to save lives,” the statement read.

It went on to say that refusal to enforce state orders, “ultimately amounts to dangerous freeloading and jeopardizes lives, small businesses, and jobs.”

The governor is in quarantine after testing positive for COVID-19.