In mid-November, Parkview Medical Center in Pueblo reached an unnerving milestone it hadn’t seen yet during the pandemic: it hit capacity, essentially overloaded with patients.

These were “extraordinarily busy days,” said Dr. Sandeep Vijan, a surgeon and chief medical officer at Parkview Medical Center. “We didn't didn't have any inpatient capacity available.”

Many of those sickened were Latino, a by-now common pattern in the coronavirus pandemic.

Vijan said those hospitalized are often elderly, on Medicare, many living in nursing facilities. Many have poor access to primary care and a host of chronic conditions, like diabetes, obesity and high blood pressure.

“They're very vulnerable. There's no question,” he said. “I think what we're seeing today is exactly what we saw in the first wave.”

With a surge in cases, even more people of color are getting sick and testing is even more delayed.

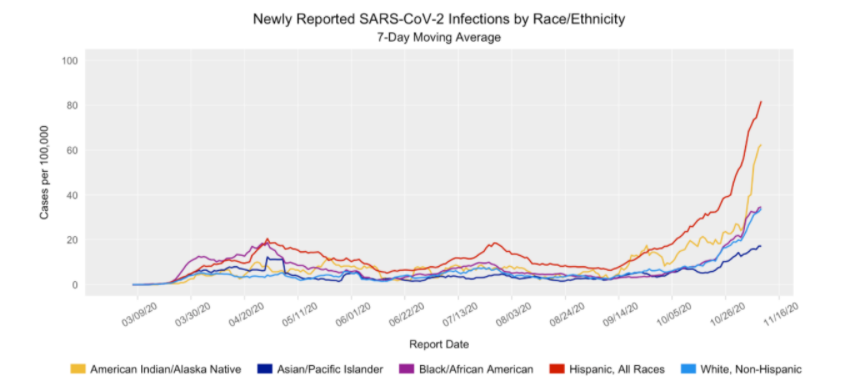

A third wave of infections has hit Colorado, and as with previous waves, people of color are getting sick at higher rates. According to state data, newly reported infections for Hispanic and Native American populations shot up starting in early October.

Now, the seven-day moving average of newly reported coronavirus infections is at 80 cases per 100,000 people for Hispanic residents and more than 60 cases per 100,000 for the American Indian and Alaska Native population. In both cases, the infection rate is more than quadruple what it was two months ago.

“In the last couple of weeks, we've really seen an exponential rise with even more sick patients,” said Dr. Pamela Valenza, the chief health officer with Clinica Tepeyac, a community health center that serves Denver’s mostly Latino neighborhood of Globeville.

The clinic runs a test site and Valenza said in November nearly half of the clinic’s patients tested positive, its highest month to date.

“We've seen a number of different families with multiple family members positive. We know families who've had multiple deaths,” she said.

Recently, the spike caused serious delays in test results. Valenza said access to testing supplies have improved, but turnaround times for results at Clinica Tepeyac can be up to 10 days from the state lab. Delayed test results can lead to delayed quarantine, potentially allowing for the virus to spread more rapidly.

A spokesperson for the health department said in the fall, the state lab and numerous private labs had backlogs but its overall turnaround during that time frame was less than 6 days.

To speed things up, community testing sites like Clinica Tepeyac now send samples to a private lab.

In the meantime, the third wave appears to be accelerating mental health and related problems in the hardest-hit communities.

“What I'm really seeing is higher rates of anxiety, higher rates of depression,” said Juan Carlos Hernandez Barraza, a behavioral health provider at Clinica Tepeyac. “We've also seen higher substance use as well.”

The clinic serves a high percentage of uninsured and undocumented Coloradans, many of whom are essential workers in jobs with close contact with others, like construction and foodservice.

“In terms of this next, third wave for the population that we serve, it's even more precarious,” said Jim Garcia, CEO of Clinica Tepeyac.

Indigenous Coloradans are also getting infected at higher rates.

While nationally Indigenous residents have seen high rates of infection, in Colorado they were not as affected by earlier waves of the virus.

After an initial surge last spring things were quiet, said Karen Hoffman, who directs primary care for Denver Indian Health and Family Services. But now a lot more patients test positive.

“We're seeing two to five positive tests per week where we were going weeks without seeing any positives during the summer,” she said.

State data show COVID-19 infections in that group rose decidedly in recent weeks, roughly as sharply as among Hispanics.

Many of her Indigenous patients work in service industry jobs or use public transit, both of which bring more risk of transmission. Hoffman said there are other factors driving the spread: poverty, homelessness and a distrust of institutions, including the health system.

“In the metro area, there's a very large financial disparity, so there's just that poverty, underlying poverty is difficult for any culture,” she said. “But especially when you just don't have the trust of the government to help you.”

Health care disparities in the Native American community go back centuries. Though gains have been made in recent decades, deep disparities in everything from income to infant mortality remain.

Many of Hoffman’s Indigenous patients live in multigenerational homes where keeping a distance between older and younger relatives is hard. For example, in one family who comes to the clinic for care, the grandfather caught COVID-19, perhaps from work.

He and his wife both ended up in the hospital, Hoffman said. Three of five daughters and two of eight grandchildren also came down with the virus “cause they all live in the same home. They’re not really able to isolate themselves.”

There are deep underlying causes for health disparities for both Native American and Hispanic communities.

According to data from Denver, Native American residents represent 0.4 percent of Denver County’s population but account for six times more cases and more than three times more of the deaths. The Latinx community accounts for 29 percent of Denver’s population and 52 percent of COVID-19 cases, 54 percent of hospitalizations and 34 percent of deaths.

“The Latinx and Native American communities have been devastated, especially in Denver County,” said Dr. Lilia Cervantes, an internal medicine physician and associate professor in the department of general internal medicine at the Anschutz Medical Campus. “It is perhaps not surprising that the neighborhoods most affected are those that have the highest proportions of Latinx and American Indian/Native Alaskan communities.”

Physicians say Colorado needs a deeper look at underlying causes for the disparities in who is getting sick and dying.

“I think that the state is well overdue for a top to bottom analysis and a recommendation for a series of changes in regards to health equity and health justice,” said Dr. Tamaan Osborne-Roberts, a family physician and the first person of color elected as president of the Colorado Medical Society.

“These inequalities in health care are outside the four walls of a hospital,” Vijan in Pueblo said. “It's about access to regular, good primary care. It's about health literacy and health education and practices that keep you healthy before you need me in a hospital.”

Osborne-Roberts said a blue ribbon commission on health reform more than a decade ago paved the way for far-reaching changes in the state in insurance and services for vulnerable communities.

“I think it's time for, if you will, perhaps a little facetiously, a Black or brown ribbon commission to take a look at those sorts of things,” he said.

Osborne-Roberts suggests the effort starts in the legislature and partners “with many different entities within the state to comprehensively address these issues so that some of the disparities that we're seeing do not occur in any future pandemics.”