When Charles Wynn received the email to participate in the clinical trial for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, he almost deleted it.

He only stopped because his wife Lisa told him not to.

“I was excited for Charles when he got the email, and I wanted to join the study,” Wynn told Colorado Matters. She’s an OB/GYN at Highlands Ranch Hospital, and as a medical professional, she was eager to be part of the trial and convinced her husband to do it. “Many of us knew that UCHealth was going to be included in the Moderna trial, and we had asked if we could participate.”

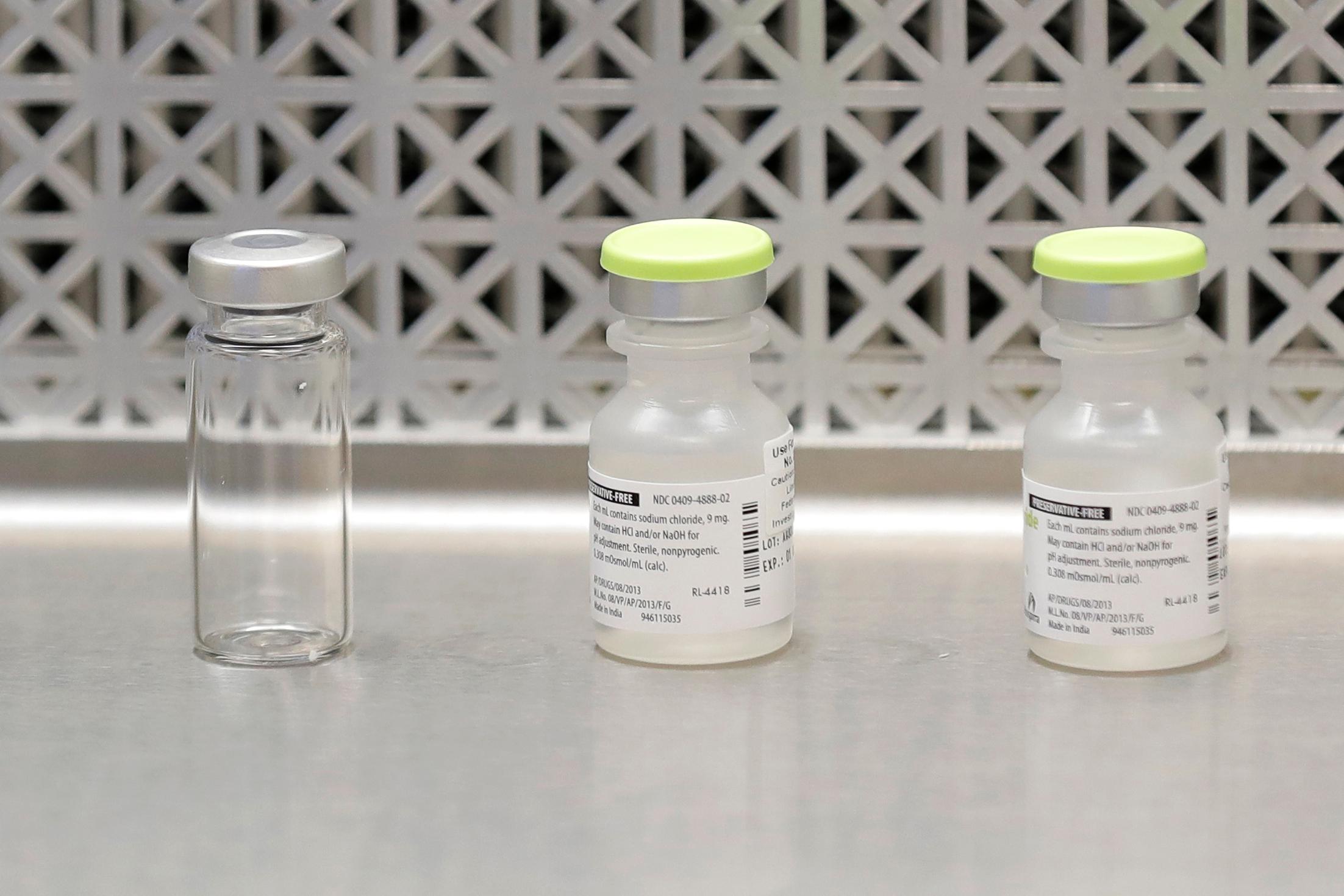

The clinical trial at UCHealth was the third phase of testing for the Moderna vaccine.

It was a placebo-controlled, double-blind study, meaning that half of the 217 participants either received the vaccine or received a placebo, and neither the participants nor the staff administering the trial knew who got what. The participants received the first of the two-shot series after an extensive physical exam, then the second after 29 days.

The trial showed the vaccine was 94 percent effective in preventing COVID-19 symptoms.

Dr. Thomas Campbell, a professor of infectious disease at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the lead investigator at the UCHealth trial site, said among the people who got sick after receiving the vaccine, they were less likely to develop severe symptoms.

“We don’t yet know whether these vaccines prevent transmission to other individuals,” he said. “That’s something we will learn in the coming months.”

Because of this unknown, doctors still recommend people continue to wear masks and practice social distancing even after receiving the vaccine until more is known about its effectiveness.

Since the study is still going on, the Wynns don’t know whether they received the vaccine or the placebo, but they feel optimistic.

“It’s kind of like Willy Wonka, and you’re waiting for that golden ticket, and you’re hoping that you already have the vaccine as opposed to having the placebo,” Charles said. “But it’s excitement too, to know that we’re close to finding out either way.”

In addressing concerns over whether the vaccines were developed too quickly, Campbell said it was important to understand the role of technology and the outpouring of support for the vaccines. He said the speed was not due to cutting corners, but rather that the genetic sequence had been determined quickly and the information was rapidly disseminated so that companies could design their vaccines based on existing vaccine technology. Additionally, the reason there hadn't been data on the efficacy of the vaccines was because of the virulent nature of COVID-19.

“People who joined the trials got sick at rates that were much faster than anyone expected,” Campbell said. “That allowed us to get the answer faster.”