It's has been a big week for news of the COVID-19 vaccines: The first Coloradans started receiving the Pfizer vaccine just as the Moderna vaccine went before the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use authorization consideration.

Everyone has a ton of questions about these vaccines. CPR's Colorado Matters turned to Dr. Anuj Mehta, Dr. Thomas Campbell and Gov. Jared Polis for answers.

Got a vaccine question? Send us an email at [email protected]

When is it my turn to get the vaccine? What phase of the plan do I fall into?

The short answer is: We don’t know. There are dozens of different factors that could decide what phase of the plan you fall into, and the people making the decisions are on the local level: your county health department, your primary care physician, etc.

Polis said two main principles are guiding the state’s system: “The first is to save lives. You are far more likely to save the life of a 70 or 80-year-old with the vaccine than you are a 20, 25-year-old. The second goal is, of course, end the pandemic.” Prioritization is based on who benefits the most. A thousand different decisions will factor into it, so it’s best to continue to check in with your doctor.

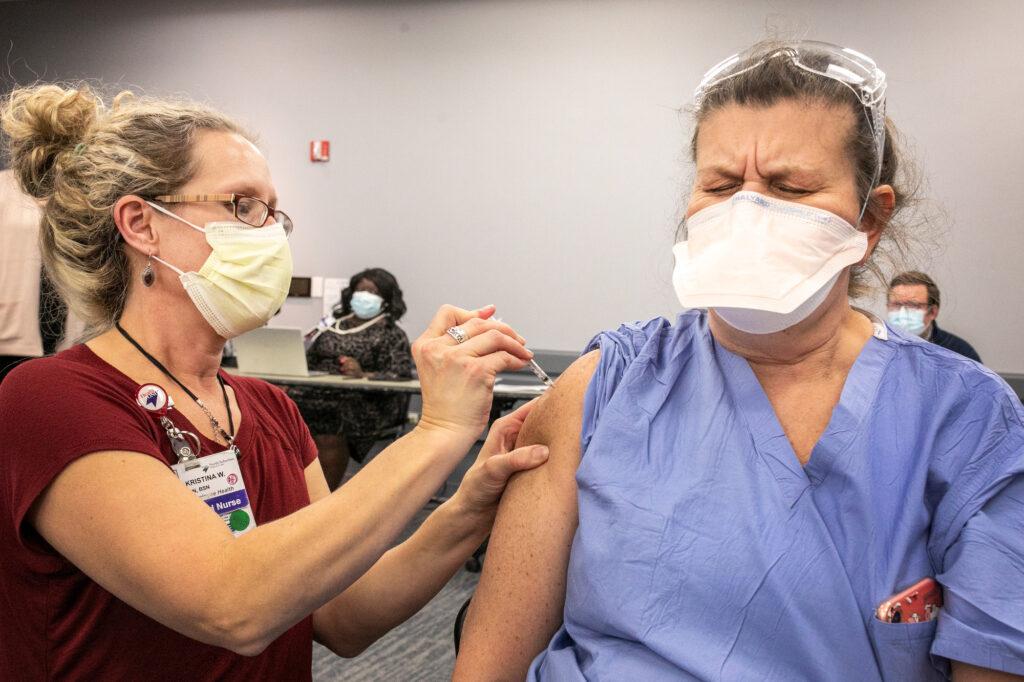

Where will the vaccine be available? Will I be able to get it at my doctor’s office? At the local pharmacy?

Polis said in the future (likely in the summer), when the vaccine is no longer constrained by limited quantity, it will be widely available to anyone who wants it, much like the flu vaccine: you can go to your doctor’s office, you can go to the CVS down the street, anywhere you would ordinarily go to get a shot.

Will I need to get the vaccine regularly, like the flu vaccine?

Dr. Mehta said we don’t know at this point.

“The data from the Pfizer and the Moderna trials suggest the immunity is very strong, even five months after the second dose of either vaccine, but really we need to wait a little bit longer to see what happens in long-term follow-ups to tell us how long the immunity is going to last.”

Is this vaccine dangerous to people with allergies? Should I still get the vaccine if I have severe allergies?

The current recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is that, if you’ve ever had a severe allergic reaction to an injection medication then wait a couple of weeks before you get the vaccine. Since we’re currently in the middle of vaccinating on a wider scale, doctors will soon get more information on how people with allergies will react.

If I already got COVID-19, do I still need to get vaccinated?

Dr. Mehta said if you’ve had COVID-19 in the past three months, you can actually wait a little bit longer before receiving it, “so somebody with no immunity can actually get the vaccine.” However, he’s still advising all of his patients who have had COVID-19 to get the vaccine, since the trials have shown no additional safety or efficacy concerns in people who have already contracted the disease. Polis tested positive in late November, and he said he plans on receiving it.

What will it cost? If I’m uninsured, will I have to pay?

Polis said the vaccine will be free for everybody. He said Congress is currently considering bills that will pay for the distribution.

How is the state addressing racial disparities with the vaccine rollout?

Polis said initial research shows there’s skepticism on the reliability of the vaccine in Black and Hispanic communities. The state’s plan for outreach in those communities is to recruit leaders who can lend credibility to the vaccines.

“It’s not me or even the doctors as the main messengers — it’s community leaders and faith leaders,” Polis said. “We are convening them and we are working with them to establish a higher degree of confidence.”

The governor also said that it’s important to note that the disproportionate effects of COVID-19 on communities of color are not because of race entirely, but rather a confluence of societal factors.

“You are not at a higher risk simply because of your race,” he said. “It is not any biological aspect of race that places you higher at risk. There are certain things that correlate with race — that might be pre-existing conditions, that might be the type of job you have.”

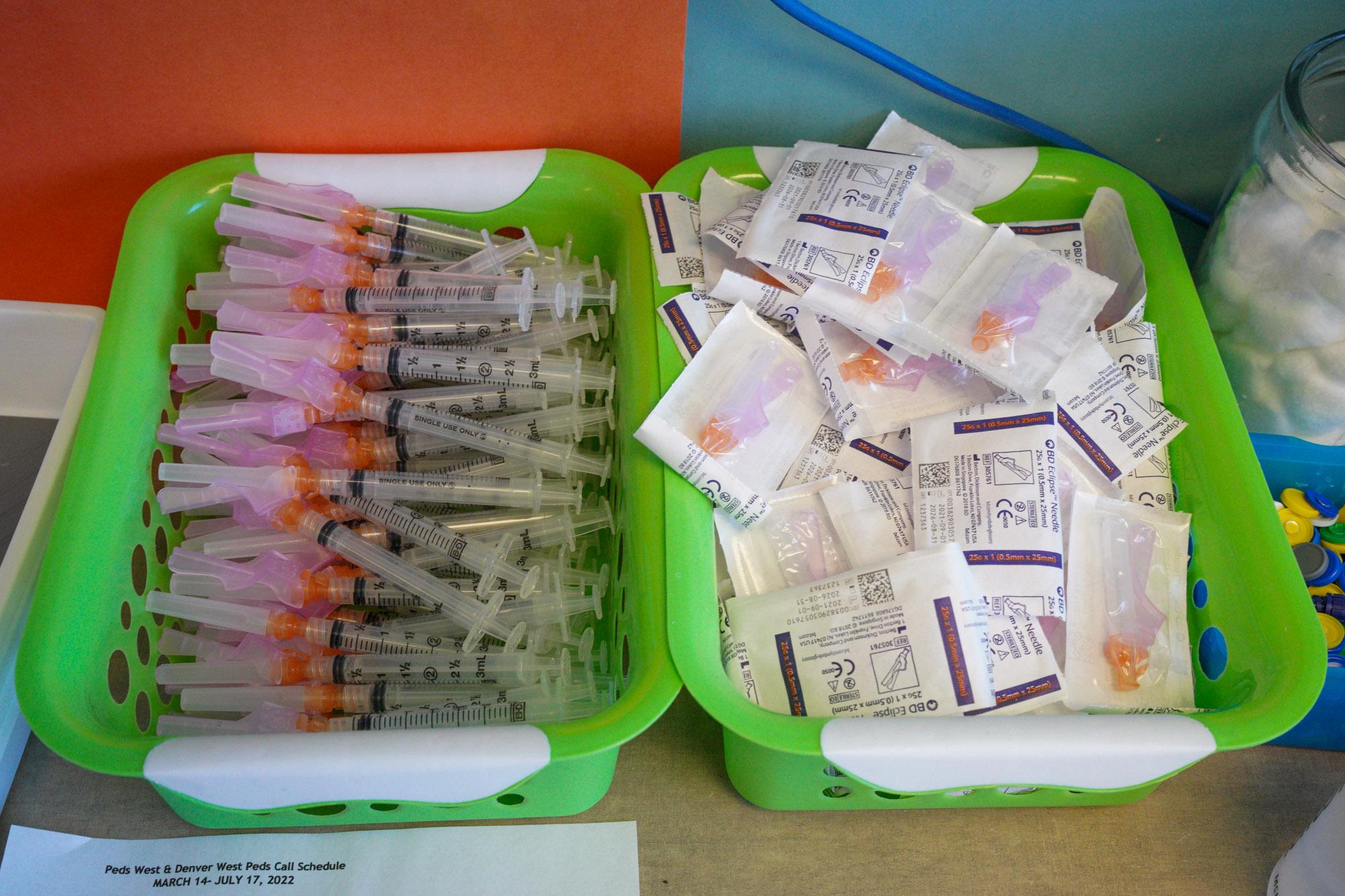

Is the vaccine two shots? How much time in between?

Both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are a two-shot series. For Pfizer, the time in between is three weeks. For the Moderna vaccine, it's four weeks.

Both vaccines are more than 90 percent efficacious, but does that mean I could still get it?

Yes. Dr. Campbell said the trial showed there were people who received the vaccine and also contracted COVID-19. However, in those people, the symptoms were much less severe than the people who received the placebo and also caught the virus. We still don’t know if these vaccines prevent transmission yet, but Dr. Campbell said that a major victory for this vaccine would be a lessening of symptoms: If we can nullify the effect of COVID-19 to that of a common cold, then it will have done its job.

The vaccines were developed so quickly, does that mean Pfizer and Moderna cut corners?

No. Dr. Campbell said the reason these vaccines were developed so quickly was because of a convergence of events. First, the technology: COVID-19 was recognized as an illness last December, and within a month the genetic sequence had been determined and made available via public domain. Then from there, companies were able to design their vaccines based on that information and also based on vaccine technology from other infectious diseases.

There was also a great amount of collaboration between scientists and industry and government. Scientists were able to develop the vaccines and the companies were able to mass-produce them so quickly and effectively because the government and industry put forth the money and resources to smooth the process. And then in the trial phase, there was a lot of support and enthusiasm for the participation. Dr. Campbell said they didn’t have to convince anybody to be part of it — in fact, people came to the trial wanting to participate.

And then, tragically, the virulence of the disease also sped up the process.

“People who joined the trials got sick at rates that were much faster than anyone expected,” Dr. Campbell said. “That allowed us to get the answer faster.”