Read in English | Leer en español

Fire crews and government officials who respond to wildfires that threaten communities are tasked with making sure all residents are safe and spared from their destructive paths.

In Colorado’s Eagle and Garfield counties, that lesson was hard-learned.

The Latino population in this vast region west of Denver has remained high over the last decade; both counties are nearly 30 percent Latino, according to 2019 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. About a quarter of all residents speak Spanish at home. Many of them handle jobs in the construction, service and hotel industry, laying the foundation for the region’s rich tourist and resort economy.

Yet as recently as 2018, they were thought of second when it came to alerts about life-threatening wildfires. Incident management teams had no multilingual members, information was not translated into Spanish and emergency response lacked cultural sensitivity for a community often victimized by immigration enforcement, according to county officials and nonprofit leaders.

Latino nonprofits are working to make sure Spanish-speaking people in Colorado get information about wildfires right away and in a language they understand. For them, it’s a matter of “life and death,” said Jasmin Ramirez, a program coordinator of Voces Unidas de las Montañas, a nonprofit based in Garfield County.

“It's a long time coming for our community to be acknowledged as members of the community that deserve to have access to the same amount of information and resources as everybody else,” Ramirez said.

The 2018 Lake Christine Fire was a watershed moment for officials who realized they were not reaching out to a key population in the region, said Eric Lovgren, the fire mitigation coordinator for Eagle County.

A group illegally shooting tracer rounds ignited the fire, which burned a large swath of Basalt Mountain and threatened several communities on the Fourth of July holiday.

First responders quickly ran into problems, Lovgren said.

The incident management team, which hailed from northern Idaho, had no Spanish speakers. Latino residents evacuated from a mobile home park in El Jebel panicked after officials told them they would need special cards to re-enter. Those cards were printed on green cardstock and references to “green cards” confused them with the immigration document. There was an underlying fear within the mobile home park, which is 70 percent Latino, that undocumented residents would be turned over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Lovgren said.

“It seems like such a small thing, but it rippled out,” Lovgren said about the green cardstock.

Communication and representation

County governments aren’t the only groups that share information about a fire. That task can be split among local, county, state and federal agencies depending on the location of the fire and what services are affected.

Bryana Starbuck, a Latina communications consultant based in Glenwood Springs, believes it is up to each agency to improve their language and cultural outreach so that all members of a community feel included and are properly informed — especially during emergency situations.

“It's always going to be a challenge, because depending on what the incident is, where it is, what kind of incident it is, the people responsible change,” Starbuck said. “It is the responsibility of all of these groups to come together to make sure that there aren't gaps in who and when things are being communicated.”

Others feel outreach would be improved if there was more Latino representation in positions of authority in the region.

- When The Wilderness Meets The Urban, Homeowners And Neighbors Are On Their Own Against Wildfires

- Stronger Building Codes And Other Rules Can Save Homes From Wildfires. So Why Doesn’t Colorado Have A Statewide Law Mandating Them?

- Colorado’s East Troublesome Wildfire May Signal A New Era Of Big Fire Blow-ups

“It's important to have diversity throughout all of these roles across the valley, whether it's at a nonprofit or a government function, because the value is that you're going to have diversity in response,” said Ramirez with Voces Unidas de las Montañas — “United Voices of the Mountains.”

The group formed in May 2020 to address what it saw was a lack of support for Latinos in Eagle, Garfield and Pitkin counties. They began by sharing information about COVID-19 in the pandemic’s early stages, though the focus soon grew to include wildfires.

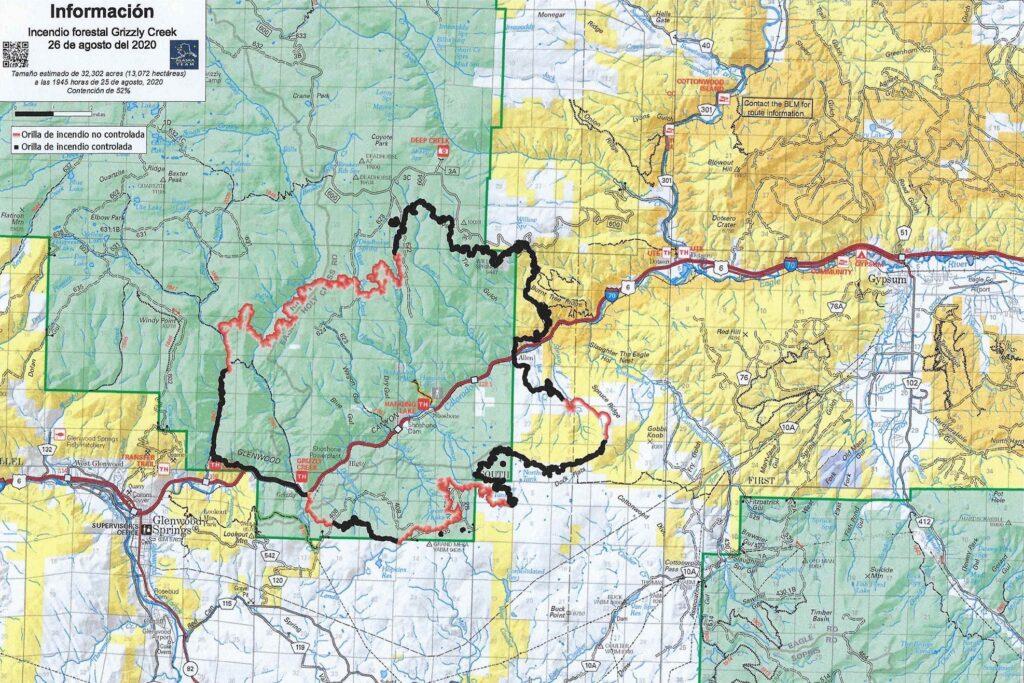

On Aug. 10, 2020, after a dry and warm spring, the Grizzly Creek Fire ignited in the Glenwood Canyon in Garfield County. It would grow to burn more than 32,600 acres, and serve as a prequel to even larger wildfires that would burn and scar Colorado.

Voces Unidas and other residents pushed Garfield County to immediately release fire information in multiple languages. Walter Stowe, the public information officer for Garfield County Sheriff’s Office, said that residents’ questions about multilingual releases should be sent to the incident management teams and that Spanish-speaking residents could use free translation services.

“Our budget constraints and financial demands, especially in these economic times, do not allow for our postings on Facebook or our press releases to come out in Spanish, Polish, German, Russian or any of the other ethnic languages that have made their home in our community,” Stowe said in an email.

Emergency linguists

Elizabeth Velasco, a professional Spanish translator and interpreter based in Glenwood Springs, was near the wildfire when she received a text from firefighters. It was a press release about the Grizzly Creek Fire. They were wondering if she could translate it.

Velasco directed her small translation agency to translate the press release and dozens of others in the months that followed. First responders relied on her so much that she ended up signing a contract with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to continue working as emergency teams switched in and out.

Velasco wasn’t just translating word-for-word like many free online services do: She was providing information that made sense for Spanish speakers.

“They didn't want just anybody. They wanted somebody that could interpret and translate the information correctly,” she said. “They didn't want it to be a mess. They didn't want there to be any confusion.”

Her team translated daily reports from the fire, along with information about smoke levels, road closures and evacuations. They dubbed videos from the fire management team and answered questions that came through Facebook. They did mountain tours with the media and were interviewed by local Spanish radio stations.

“I think we became experts right away,” she said. “It's always way better when you have experts and linguists in your team to make sure that the message is correct.”

Her team’s efforts made a difference, she said. She could tell based on the number of people who would reach out on the fire webpage, tune in to the radio to ask them questions or watch their videos. Together with a Latina geographer, they created the first bilingual map of the Grizzly Creek Fire.

Velasco is preparing for the upcoming wildfire season by taking FEMA classes offered to public information officers. In Eagle County, Lovgren hopes to one day see more bilingual staff focused on sharing information about wildfire mitigation and preparedness.

Now removed from both the Lake Christine and Grizzly Creek fires, Ramirez and other Latino residents are hoping that Spanish speakers in the region are immediately included when it comes to communicating information during any future wildfires, and not seen as an afterthought.

“We need to decide what kind of county we are going to be five years from now, or one year from now, a couple months from now when fires do come back to the valley,” she said. “Are we going to be prepared?”