Colorado is supposed to debut a grand political experiment this year: having a public commission, not elected officials, redraw the state’s Congressional and statehouse boundaries. The process is already threatened by delays out of its control.

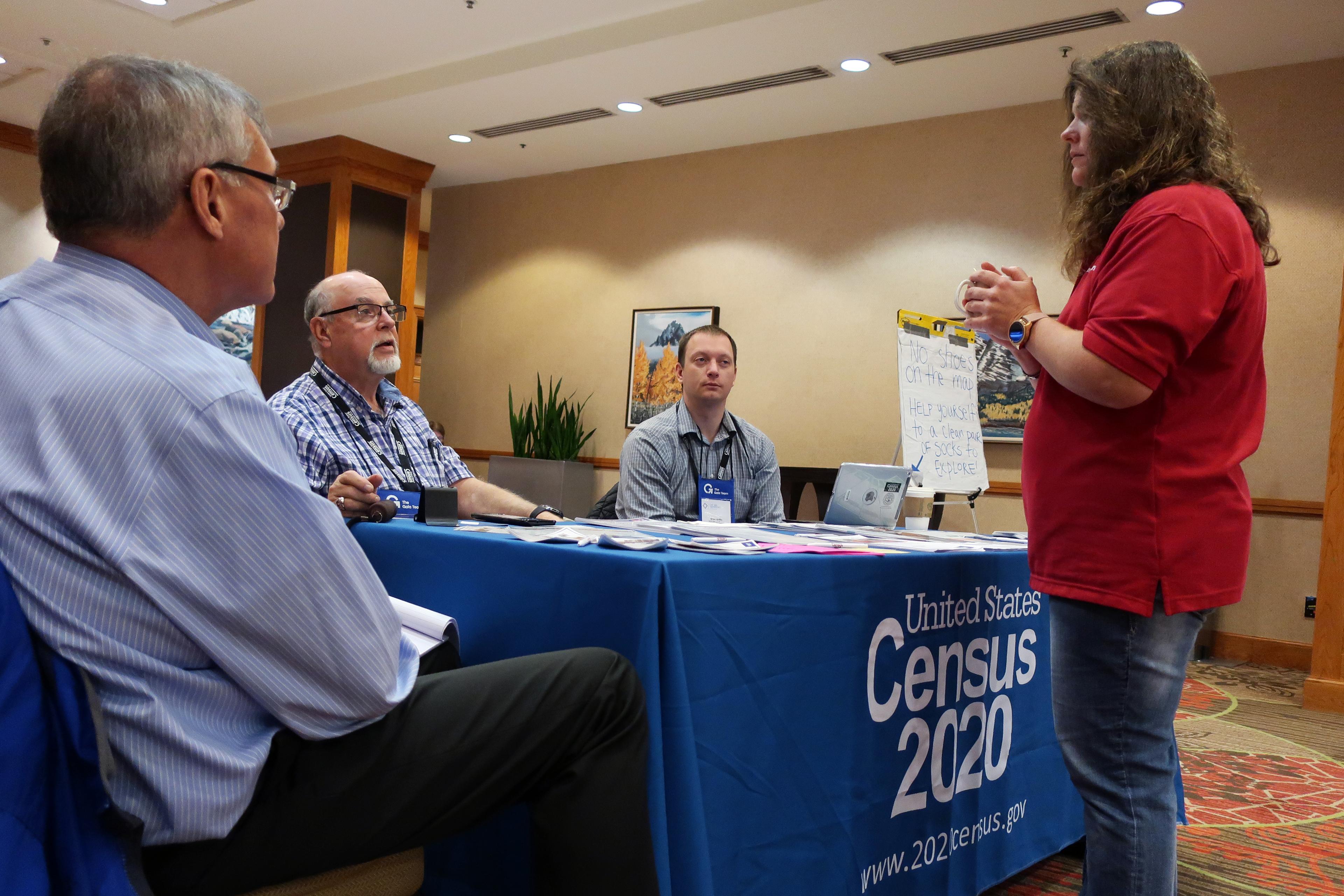

In 2018, Colorado voters overwhelmingly approved a new process for setting the districts for state and federal races for the next decade. The goal is to make seats more competitive, get broad public input and inject more fairness and transparency into how political lines are set.

What voters couldn’t have anticipated was that the data Colorado and states across the country need to begin redistricting might not arrive in time to make the new process work.

“We don't know when we'll get the data; when we'll be able to start drawing plans,” said Jeremiah Barry, the staff attorney for Colorado’s Independent Redistricting Commission.

The U.S Census Bureau is well behind schedule; it has been delayed both because of the pandemic and controversial policy changes by the Trump administration. The Bureau has also discovered irregularities in the census records that they need to try and fix. It’s not clear how long that could take.

“If it's only by a couple of weeks, it probably doesn't create any problems,” Barry said. “If we're talking about a delay of a couple of months, then it really backs up into those other constitutional deadlines.”

The commission has reiterated that public hearings are essential to the redistricting process and will still happen, but the schedule will likely be compressed or delayed. The state constitution requires the commissions tasked with drawing congressional districts and state legislative seats to conduct at least three public hearings on the proposed maps in each of the state's seven congressional districts.

Raising the stakes in all of this is the expectation that Colorado, after a decade of population growth, will gain an 8th Congressional District this year. That means commissioners won’t just be tweaking existing boundaries, but possibly reimagining the entire map and a newly competitive seat.

If the data comes too late, Barry says non-partisan legislative staff would be forced to submit their own final plan for the congressional and state legislative districts to the Colorado Supreme Court. But that’s a worst-case scenario.

“We're not interested in having our plan. I mean, we are staff of the commission. We want the commission to approve a plan.”

Even as the state waits on the data, some parts of the process are moving ahead as planned. On Monday, a panel of retired judges will randomly select the first six congressional district commissioners: two Democrats, two unaffiliated voters and two Republicans.