Grace McElhaney’s grandmother is skeptical about getting a COVID-19 vaccine.

But McElhaney, a 16-year-old at the Rocky Mountain School of Expeditionary Learning in Denver, has been poring over medical journals and scientific articles in her science class to prepare. Now she’s ready to bring her new-found knowledge to her grandmother.

“She is a stubborn woman, so we’ll see,” said the blue-haired high school junior. “But I think if I bring in the science, she’ll have to listen.”

Rather than just throwing contextual-less data at people like her grandmother, McElhaney and her 11th- and 12th-grade classmates have produced videos that distill their knowledge of how the vaccines work.

They’re not focusing on people opposed to the vaccine, but instead on people who'd perhaps read something on social media that has sowed the seeds of doubt — people on the fence.

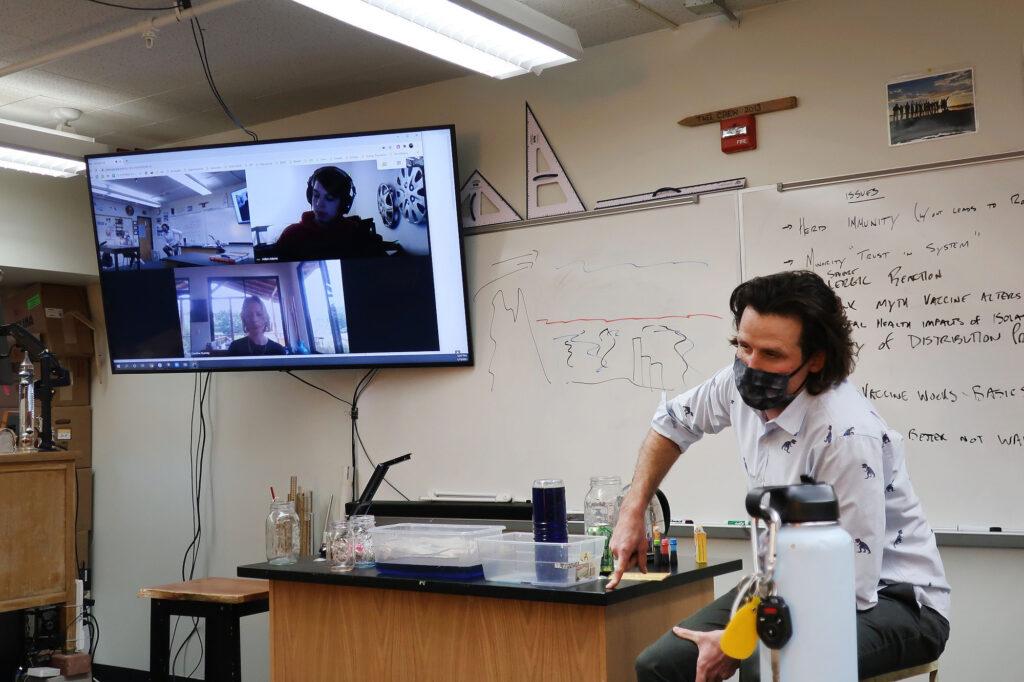

McElhaney’s science teacher, Eric Dinkel, likes to give students a voice in how they learn. He’s equally passionate about something else.

“I think this is a really important part of science,” he told his class on a recent Friday morning. “If we don’t do anything with our knowledge, what’s the point of knowing it, right?”

So, he challenged his students to come up with an activity relating to what they learn about the vaccine. First, they thought of a debate. But it turned out everyone in the class wanted to get the vaccine. That wouldn’t be any fun.

Then they talked about taking on the myths and misconceptions about the vaccine, and what it’s like to have a conversation with someone who thinks differently from how you do.

“They’re wise,” Dinkel said. “They said, ‘You always have to start a conversation like that with empathy.’”

The class explored the idea of an empirical truth in science, and how to use that truth to educate other people. As the students designed their videos, Dinkel circulated around the lab space, reminding students of how empathy is crucial when trying to encourage people to see a different perspective.

“Our goal is not to alienate or belittle,” Dinkel said. “Our goal is to recognize that people's concerns are really valid and they're rational. And so that’s your mission as scientists, is to offer them in an accessible way, entertaining way, evidence that helps them consider a different point of view.”

To start, the students researched some myths and misconceptions about COVID vaccines.

Then they studied, as this video shows, what the coronavirus is, how it’s spread, how it interacts with the lungs and the immune system response, how precisely the vaccine works, how messenger RNA gets into your cells to make antibodies to fight the virus later on.

The students say they can understand why there are so many myths and misconceptions about the vaccine. It’s new science. It’s the first time a vaccine has used messenger RNA as the molecular agent used to teach the body how to recognize and fight the virus. Hayden Wright said his group is tackling the “spooky” myth that mRNA will alter people’s DNA.

“We have to explain that the mRNA doesn't actually affect the area of the DNA, it's the layer outside of it,” he said.

In other words, messenger RNA from the vaccine never enters the nucleus of the cell and does not affect or interact with a person’s DNA. The cell eventually breaks down the instructions and gets rid of them.

Classmate Mateo Ferrell-Carretey’s own parents had a “wait and see” attitude about the vaccine. His group took on suspicions about how fast the vaccine was developed. The senior pored over medical journal articles — the methods, efficacy, results and conclusions — and discovered the vaccine faced the same rigorous regulatory hurdles as other vaccines.

Ferrell-Carretey and his classmates said they can understand why some people are hesitant. They may not have the information, and slogging through original studies can be “boring” — and most people don’t have time to do that, they said.

Ferrell-Carretey’s project partner, Maxwell Davis, is using MediBang Paint, digital painting and manga creation software, to draw characters to animate their video.

“I think it helps add a little bit of just personality to it,” Davis said. “I think it makes you feel a little more connected to the person who's talking as well.”

In the end, what convinced Ferrell-Carretey’s parents about the vaccine’s safety was seeing the medical professionals get vaccinated first.

“The people who made the vaccine took the vaccine,” he said. “If they're willing to take it themselves, I have no reason not to trust them. They're not going to throw their own lives away.”

In studies, Ferrell-Carretey read about how each trial participant was monitored and how any kind of atypical reaction was tracked, with scientists asking, “Did this abnormality, happen because of our vaccine, or because of another environmental source?”

Ryanne Straub’s group found severe allergic reactions, like anaphylaxis, are extremely rare.

“As of Jan. 11, it was only 29 people,” she said, citing the number of anaphylaxis incidents out of millions of vaccines administered.

In between editing video shoots, classmate Beth Elder said the message they’d like to get across in their video is to stay with a health provider at least 15 minutes after getting the shot.

“If you’re going to a pop-up clinic that isn’t prepared to deal with you like that or a drive through clinic that you leave before that 15 minutes is up, it can just get really dangerous if they’re not monitoring it more,” Elder said.

Two boys in another group have a powerful argument for getting the vaccine, one that resonates, especially for teenagers. If herd immunity isn’t established and people have to keep quarantining, mental health will keep getting worse.

“Everyone's worrying about actually catching the virus and dealing with the repercussions,” Sincere Milligan-Pate said. “But no one's really paying attention to what's going on behind the scenes and what's going on in people's heads.”

“Mental health could be more catastrophic than a possible side effect of the vaccine,” added his project partner Ian Zonca.

One recent study of high school students found that nearly a third reported feeling unhappy or depressed. It said teens are experiencing a “collective trauma.”

A group at the front of the class had an “explosive” idea — namely, what would happen if people don’t get the vaccine. Their video is a spoof on the 1987 public service announcement “Your Brain On Drugs,” where one’s “brain,” represented by an egg, becomes scrambled. The boys’ experiment involves dry ice, warm water, and a lot of ping pong balls and “safety glasses so you don’t get ‘exploded on,’” Charles Isley-Rice said.

The group consulted studies from John Hopkins University, the Food and Drug Administration, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The idea is if people don’t get the vaccine, coronavirus will spread through the population like exploding ping pong balls.

In the video, Isley-Rice stands in the middle of a park in a white scientist’s coat. He patiently explains an equation on a whiteboard — the rate at which people must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity, concluding it is about 87 percent with people social distancing.

Then he brings out a bucket of ping pong balls, representing the human population.

His fellow scientists pour a bottle of liquid into the bucket. The boys quickly run away, disappearing from view. A few seconds later, the ping pong balls and bucket explode in a puff of smoke, scattering in every direction.

Aside from the science, the bottom line, said many of the teens, is that taking the vaccine helps others.

“You're being selfless and helping another person by getting the vaccine,” said student Lucas Pereira-Suarez.

“There have already been millions of deaths because of this virus,” said Harper Kane. “As a young person, I'm not worried about getting the virus because I know it won't affect me too much, but I also don’t want anything to happen to my grandparents or elders or people who are at risk in general.”

Editor's Note: A limited number of CPR News journalists have started to receive vaccinations according to the state's prioritization of essential frontline workers.