Large-scale events are now part of the playbook in Colorado’s effort to distribute the COVID-19 vaccines equitably — particularly to populations of color — a feat the state has so far failed to achieve.

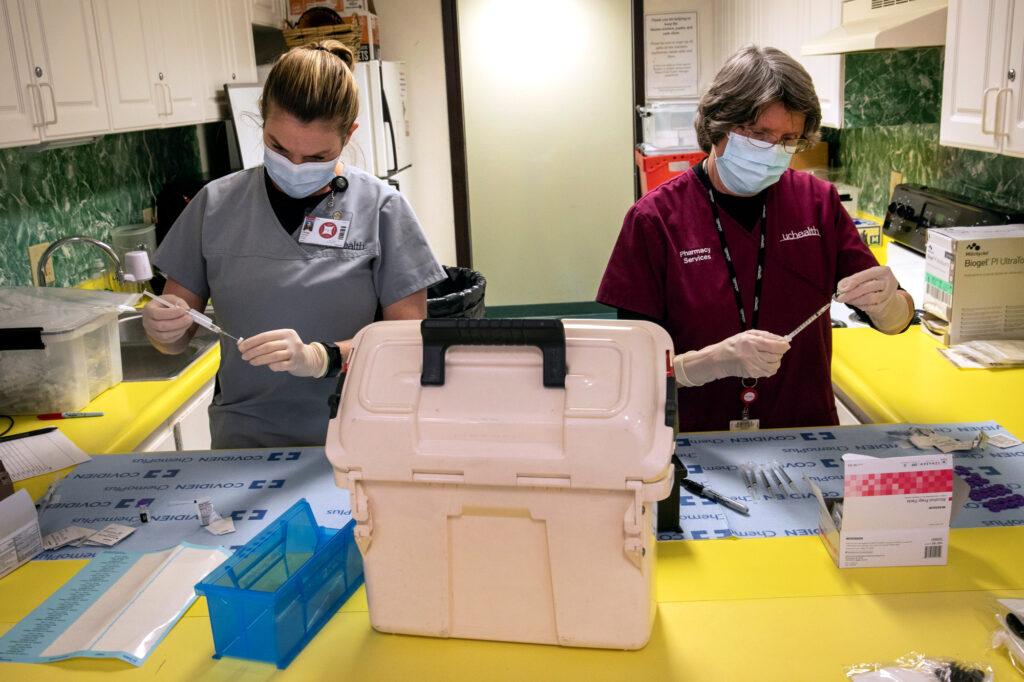

Hundreds of Coloradans ages 70 and older visited Denver’s National Western Complex Saturday to get immunized against coronavirus. On Sunday, Shorter Community African Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver held its second COVID-19 vaccination clinic in collaboration with UCHealth.

More than 500,000 Coloradans have now received at least one dose of the two-shot vaccine regimes from either Pfizer or Moderna, and about 165,000 of those folks have received both doses.

At least 73 percent of them have been white.

Danny Hermosillo, who just turned 70 in October, was with his extended family, sitting in a line of folding chairs in a large event hall at the National Western Complex. Everything was arranged so everyone was socially distant while receiving the vaccine. The group had received their shots and were waiting the required 15 minutes to ensure they didn’t experience any side effects. Since the state began vaccinating residents, Hermosillo has been waiting for his turn.

“I want to be safe,” he said. “I don’t want anything to happen to me or my family.”

Fred Gayles, 73, of East Denver, said he was anxious to be vaccinated because he has COPD, a lung disease that makes him especially vulnerable. Gayles, who is Black, said unlike some Blacks who have a historical distrust of the health care system, he was not reluctant to get the vaccine.

“I was worried more about [if and] when I could get it,” he said.

With frontline health care workers largely vaccinated, and about 35 percent of the state’s population of 70 and older residents having received at least one shot, Black and Latino residents have not been inoculated at anywhere near their rate of representation in the state’s population.

It has been a persistent problem in Colorado and across the nation in the first seven weeks of the vaccine rollout. Authorities are confident the statistics will improve as more vaccines are available and eligibility for the shots expands, but for now, the state is starting to take small steps towards correcting the imbalance.

Through the end of the week, Latino seniors were being vaccinated at about half their representation in the population. The group makes up 10 percent of seniors in the state, but just five percent of vaccine recipients. Black seniors fare a little better, making up almost two percent of vaccine recipients and just more than 2.5 percent of the senior population.

To fix it, the state has released vaccines to smaller weekend clinics run through community groups and has encouraged larger providers to target minority residents for appointments to receive the vaccine at mass events or in clinics.

The Rev. Dr. Timothy E. Tyler, pastor of Shorter Community AME Church, said that the vaccination clinic on Sunday was an intimate setting built on trust -- but he thinks it’s more than that.

“I'm of the opinion that it's, it's not so much trust as it is also access,” Tyler said. ”Right now the low numbers of Black and people of color that are getting this vaccination is not just because of trust It is not accessible to us, and it is not accessible to our communities. And so I'm more focused on that.”

William Brown arrived at Shorter to get his first shot on Sunday. He said he was initially hesitant to get the vaccine, but took his mother’s age into consideration and decided it was worth it.

“I'm usually around a lot of older people and so to protect them and myself, I figured why not get the shot? My mother is going to be 89, and my sisters told me I can't go back to New York unless I get the shot,” he said.

The bulk of vaccines in Colorado is distributed through the state’s largest health care networks, like UCHealth, Centura, Kaiser and others. They have been encouraged to use their weekly or twice-weekly allocations quickly. To do that, they have used online registration efforts and random selection from those lists to decide who gets a shot.

Those lists have been dominated by white residents.

Now, working through churches, community groups and local public health agencies, the state is starting to get more vaccines into diverse neighborhoods. For now, those efforts still vaccinate hundreds, while thousands of white residents get vaccniated in other settings. But Jill Hunsaker Ryan, executive director of the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment, said she is optimistic that the community approach will close the equity gap.

“We think that this will start to bear fruit shortly,” Ryan said in a Friday news conference with the governor. “If it’s not making a difference, we’ll do something different.”

The mass vaccination efforts are almost invariably filled with appointments in advance, so the groups don’t have more people show up than they have vaccine to give them. As the supply improves, there will likely be greater access, including through more pharmacies in neighborhoods across the state.

On Sunday, Denver Parks and Recreation Executive Director Happy Haynes was accompanying her mother to get vaccinated at the Shorter AME Church. She said the clinic was one of the only ways to get people in the church community vaccinated.

“There is already some reticence about getting the vaccine and going across town to some large mass gathering isn't going to do it,” she said. “We're lagging behind. So this is going to make a difference in making sure that all of our folks in our community will get vaccinated.”

At the National Western Complex Saturday, hundreds of volunteers worked to direct those arriving to parking spots and then inside to receive their shots.

Sharon Hay, 70, who wore a black, rhinestone-studded mask with the word “SEXY” written across it, sat next to her husband Eugene Hay, 74, waiting for their turn.

The couple, who lives in Arvada, both had COVID-19 in March and didn’t want to get it again.

At first, Sharon Hay had been worried the vaccine might not be safe, but hearing Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease tout its effectiveness, convinced her to get it.

Her husband Eugene said he was looking forward to spending more time with his grandchildren.

“I’m sick and tired of being cooped up in the house,” he said.

Chuck Murphy and Hart Van Denburg contributed to this story.