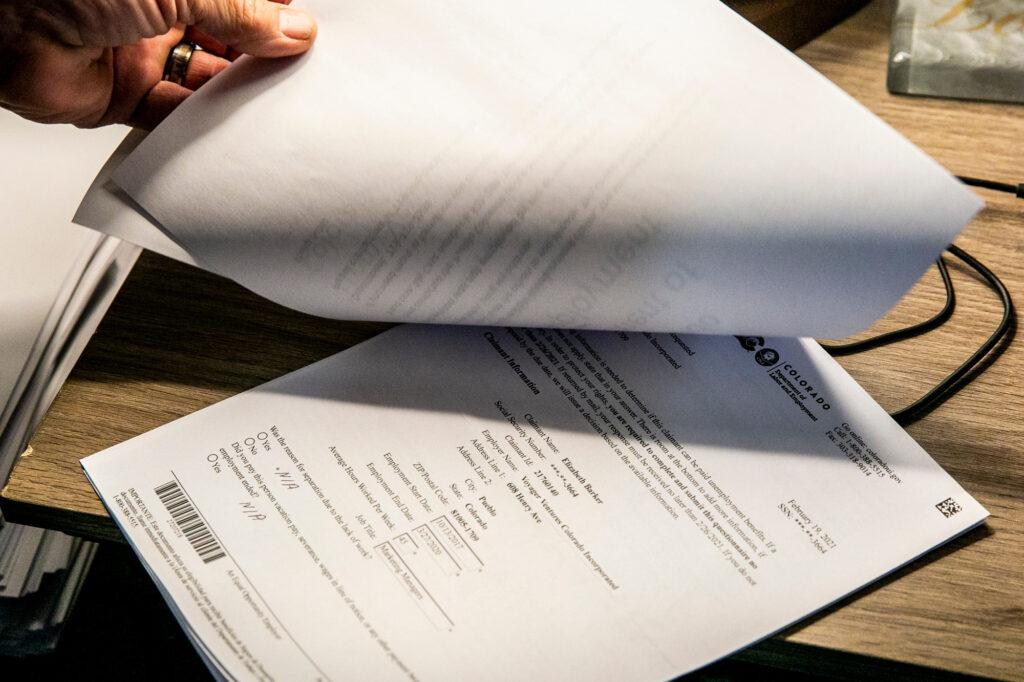

Phil Jubic’s mail usually drops through the slot at the front door of his home in Pueblo. For the past couple of months, however, he’s instead found thick bundles of letters on his front step.

“It’s gotten to the point where the mailman cannot get them in the drop mailbox,” he explained.

These days, nearly every letter comes from the same sender: the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment. Sometimes, it’s dozens. Sometimes it’s more.

“Dozens would be easy to handle. It’s when I receive 95 in one day that it gets a little difficult,” Jubic said.

Each piece of mail represents an unemployment claim: someone asking the state of Colorado to pay them unemployment benefits. They’re all claiming that they were laid off by Jubic, and the claims are packed with fictional, fantastical details.

“I have gotten these claims for a chemist, a chemical engineer, a boat engineer, a dentist, a hygienist. I get marketing managers,” he said.

In fact, Jubic is a retired delivery contractor for Pepperidge Farm. He has never had a full-time employee, much less laid one off. But for the last two months, his name has been pulled into an elaborate, nationwide pattern of fraud.

Scammers and hackers have filed millions of claims for unemployment benefits across the U.S. during the pandemic. If no one notices that they’re fake, scammers can collect thousands of dollars per week from the government.

The main unemployment program requires that applicants “prove” that they lost a job — so they make up job titles and fill in the contact information of random “employers,” like Jubic.

“These people put down that they work for 10 hours a week for me, up to 72 hours a week,” Jubic said. One claim was for a woman who supposedly had worked as Jubic’s accountant for nearly 20 years. He does not employ an accountant.

When the letters first started to arive around the beginning of 2021, Jubic didn’t understand how the scheme could possibly work.

“I couldn’t figure out how they could just make up names and Social Security numbers and stuff, and have it get through the system,” he said.

Jubic eventually discovered that the identities showing up in his mail weren’t simply made up. They were taken from real people.

When Jubic searched for one man with a distinctive name, he found a match in Illinois. Jubic has identified more than two dozen different identities used in the filings against his corporation, and each one can lead to multiple letters from the state.

“Lowe — she was one of my first!” he laughed while flipping through a thick sheaf of papers.

The aftermath of the Equifax breach

The letters arriving at Jubic’s home are a bizarre paper trail of a national phenomenon. Scammers build these fraudulent identities using personal information stolen in data breaches, like the one at Equifax. Then they send swarms of zombie-like stolen identities into state unemployment systems.

“They have enough information to file something as John Smith in Seattle, Washington, based on your address, your birthdate — they've got your phone number, too,” said Andrew Stettner, an expert in unemployment with The Century Foundation, a nonprofit think tank.

Safeguards in most benefit systems were built to stop people from lying about smaller details, like how much money they made, or when they were laid off, Stettner said. But the combination of new technology and the largest unemployment benefits package in recent history has opened up a new frontier.

“It’s become this weak link, this target,” Stettner said.

The scams first targeted Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, a federal program created for gig workers and the self-employed. The original version of the law had few security requirements, and officials in states like Colorado say they were initially focused on paying benefits to people in need, rather than preventing fraud.

In September, the U.S. Department of Labor warned of “criminal enterprises and other bad actors deploying advanced technologies, stolen or synthetic identities, and other sophisticated tactics,” according to a memo obtained by CPR News through a public records request.

The schemes were being carried out by “complex, multi-state networks that necessitate a coordinated national response,” the memo continued.

The scale of the attacks was several orders of magnitude higher than anything the state had experienced, said Cher Roybal Haavind, deputy executive director at the CDLE.

“We had 86 fraud cases in 2019. We had over 800,000 in 2020,” she said. “It was an unprecedented degree of fraud that we’ve never seen.”

The state labor department has responded by installing automated systems that search for more than 50 indicators of potential fraud. But the phenomenon has spread beyond PUA, and scammers have recently started flooding the regular unemployment program.

“They count on states being so backed up and so buried in work that they’re not even going to catch or see the fraud claims,” said Phil Spesshardt, benefit services manager for CDLE.

Battling the scammers

Labor officials estimate Colorado has paid out about $4 million to these types of scams. Other states have reported far larger numbers — including $11 billion in California.

The fraudulent applications can also cause trouble for the individuals involved. A person whose identity was stolen might have trouble applying for their own unemployment benefits if they genuinely need them. Meanwhile, a supposed “employer” like Jubic could get a mistaken bill from the unemployment insurance program if the fraud isn’t caught.

“If the state comes back on me for these claims, takes my money, then it's me — I'm out in the street,” Jubic said.

When he first started to receive the letters, Jubic would drive to Office Depot to fax his replies back to the state, since he couldn’t figure out the online appeals option. Soon enough, he found himself paying out $20 per visit.

“It just gradually got larger and larger,” he said. “Finally, we broke down and we bought a correlating fax-copy printer — to where I can fax about 30 pages at a time.”

He’s following the instructions on the documents as best he can, but in return he’s only received more notices of claims and form letters from the state, he said.

In fact, state officials said Jubic should take a completely different route — one that isn’t detailed in the claim notices. CDLE is asking Jubic and others to fill out an online form to report fraud.

It’s also not clear whether the state is actually paying out benefits on the claims against Jubic. The state’s new unemployment software, MyUI+, is hard-wired to send letters to employers about each claim, whether or not the anti-fraud system has stopped payment.

And each time Jubic responds, it automatically generates more paperwork. Spesshardt said the department was working to make the process more clear.

Eventually, CDLE officials say they will be able to stamp out most fraud. They are slowly deploying a privately owned service known as ID.me, which uses “video selfies” and other technology to check identities.

It’s an acknowledgment, in essence, that dates of birth and Social Security numbers have become obsolete. It’s not clear yet how well the new technology will work, and it’s already created frustrations for some people seeking benefits.

Meanwhile, Jubic continues his battle.

“I’m a stubborn S.O.B., I’ll tell you that right now,” he said, “and I don’t want those people to get a dime.”