After years of air pollution releases at the Suncor oil and gas refinery in Commerce City, Colo., Olga Gonzalez is glad to see plans for real-time air monitors in the largely Latinx neighborhoods around the facility.

She isn't sure people in the community are ready to trust the company, the state or the city to run those networks.

“Our own independent monitors would inspire greater trust amongst our community,” Gonzalez said. “That’s what we're trying to do here.”

Gonzalez is the executive director of Cultivando, a Commerce City nonprofit that helps residents get involved in local politics. The organization is now bidding to build air monitors to track pollutants escaping the Suncor facility, Colorado’s only oil and gas refinery.

While state lawmakers and Suncor have recently promised similar monitors, the Cultivando plan would set up a system that’s separate from both the company and the government. Gonzalez said that would provide an extra layer of verification. More importantly, she said the independence might be necessary to overcome skepticism borne from decades of environmental racism.

“Equity and justice? Those are just buzzwords if they’re not truly led and informed by those who are impacted,” Gonzalez said.

Bottom-up accountability

The Cultivando plan is among more than a dozen proposals vying for fine money from Suncor. In March 2020, the Canadian company agreed to pay more than $9 million to settle multiple air pollution violations with state regulators. Of that, $2.6 million was set aside for community projects.

The fate of the community project funds lies with an 11-member panel of Adams County and North Denver residents convened by the state. Proposals include plans for expanded health clinics, electric school buses, solar energy job training, tree planting and other projects. A final decision is due by the end of March.

Maria Zubia, a panel member and the director of community outreach at Kids First Health Care, a school-based health clinic in Commerce City, couldn’t speak about specific applications but said she sees a need for more air monitoring.

Zubia recalls when a refinery accident rained clay-like dust on the city in December 2019. After noticing the substance on her black SUV, she couldn’t find any information about the overall air quality around her clinic. Zubia didn’t know what to tell her patients or staff until Suncor replied to her emails, saying the substance was harmless and their own tests showed normal levels of air pollutants.

Zubia said the incident showed her a deep need for air monitoring in the community. She said it should be easy to find trustworthy information about any potential health threats during pollution events.

“It should be run by experts,” Zubia said. “It shouldn’t be a political thing.”

A community vision for environmental justice

Cultivando has asked for more than two-thirds of the community project funding for its air monitoring network, which would include one fixed air monitoring site along the perimeter of the refinery, one built into a mobile van that checks for air pollution in the adjacent neighborhoods and several smaller air monitors for homes and schools. The data would then be published on a public website.

To build the network, Cultivando would contract with Boulder A.I.R., an environmental consulting firm already running similar air monitoring sites in Boulder, Longmont and Broomfield. Detlev Helmig, a former atmospheric scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, owns and operates the company.

If given the Cultivando contract, Helmig would monitor a wide range of air toxins, including hydrogen cyanide, a colorless gas classified as a chemical weapon. The pollutant is also a common byproduct of petroleum refineries, but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does not limit emissions, leaving the task to states. In 2018, Suncor broke a 12.8-ton emissions cap before asking for a higher restriction of 19.9 tons per year. State regulators are currently considering whether to grant the request under Suncor’s new operating permit.

State regulators have found no evidence of dangerous hydrogen cyanide levels near Suncor. Andrew Bare, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s Air Pollution Control Division, said the March 2020 settlement funded two rounds of monitoring in the neighborhoods around the refinery. None of the samples picked detectable levels of the gas.

Helmig hopes any future results would further assure residents, regulators and Suncor.

“I think it’s in everybody’s benefit to understand the potential emissions and impacts on air quality,” Helmig said. “The better the data, the quicker it can be provided, the better position to take action.”

A rush for new air testing

If it’s approved, the Cultivando proposal would add to an already complicated air monitoring landscape involving the state, city and Suncor.

Colorado air regulators currently maintain three permanent air monitoring sites near the Suncor refinery. Last week, Democratic state lawmakers announced plans to introduce legislation that would require the company to fund new state air monitors along the refinery’s property line. Suncor must also fund continued hydrogen cyanide monitoring under the March 2020 settlement agreement.

In addition to those requirements, Suncor has agreed to set up its own community testing program. According to its announcement, the company will hire an “independent expert” to develop the system, which could include sensor-based monitors and mobile testing labs. Suncor spokesperson Mita Adesanya said the company is hoping to roll out the first stage of the testing system this summer.

Domenic Martinelli, an environmental planner for Commerce City, developed a separate plan for a monitoring network operated by the city itself. It would deploy low-cost sensors to track particulate matter and volatile organic compounds in a two-mile radius around the refinery. It’s now competing with Cultivando for the Suncor settlement money. If the citizen panel ultimately chooses the nonprofit, Martinelli said “we’re all absolutely supportive of it.”

“The goal is to make sure that community citizens and residents have the ability to access that information in some form,” Martinelli said.

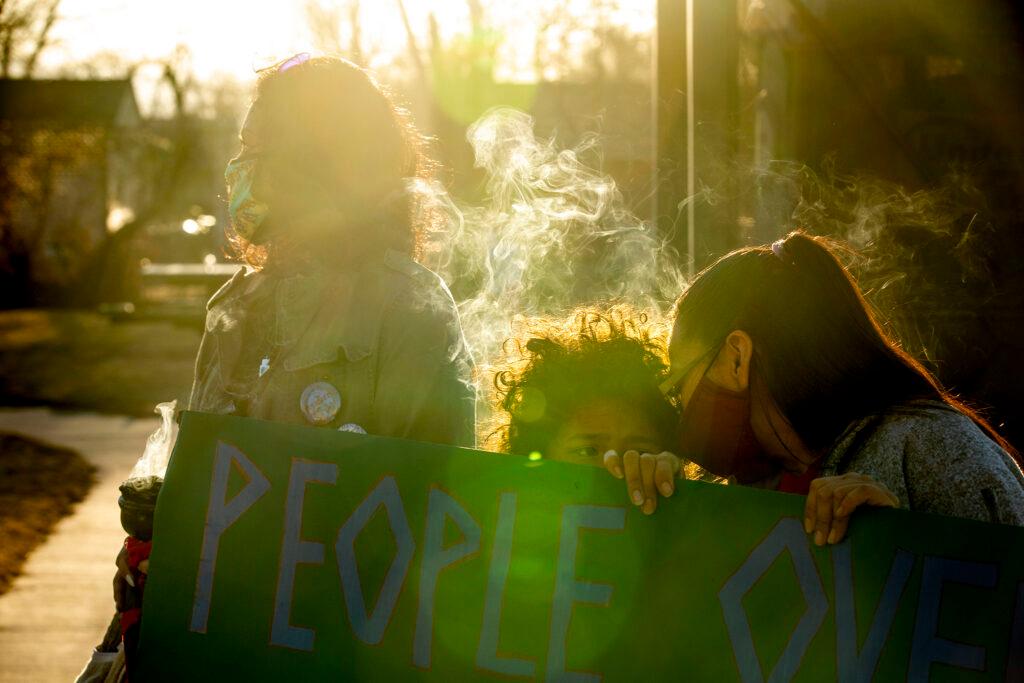

Despite all those plans, Laura Martinez supports the Cultivando proposal. The mother of three attended a recent rally calling for more environmental action against the refinery. While her kids scaled a jungle gym, she said she trusted the nonprofit since it was independent from Suncor. She worried the city relied on the company too much for tax revenue and charitable donations.

“If you have something to gain from that entity, the results could be skewed,” she said.

Miguel Otárola contributed to this report.