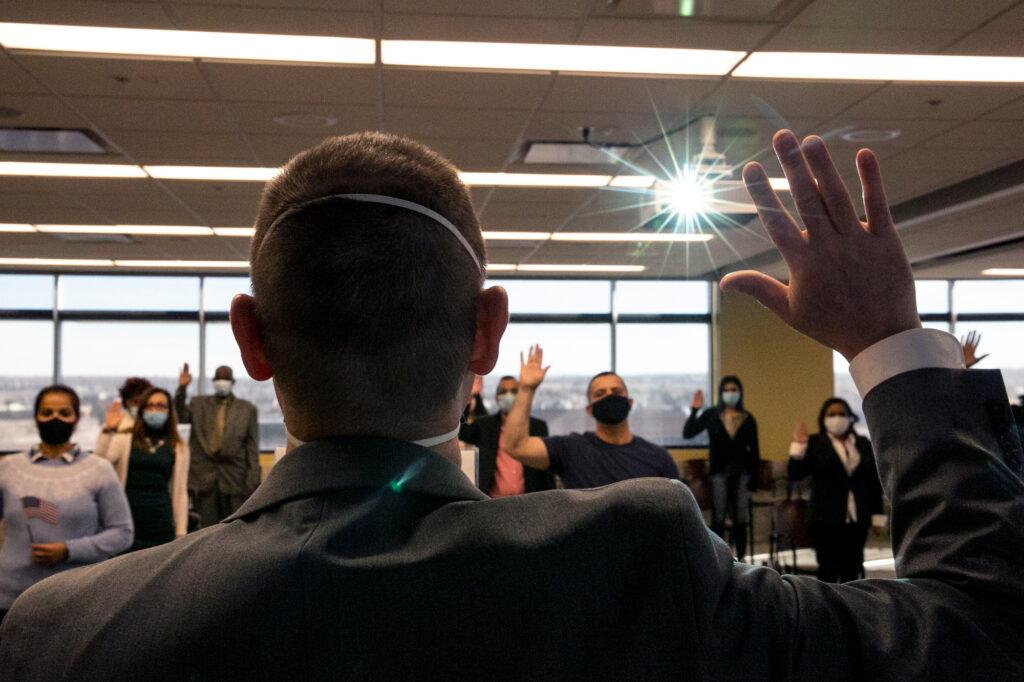

Wendy Shu waited a long time for this day. She took her seat in a large, but mostly empty room with 11 other people at the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services field office in Metro Denver. Everyone wore masks and sat eight feet apart, ready to take the Oath of Allegiance to become United States citizens. At the front of the room, a man stood in a suit, also wearing a mask.

“You’ll look around the room, there’s a lot of empty space,” said Andy Lambrecht, the director of the USCIS Denver branch.

“Normally our ceremonies would be packed full of family and friends here to celebrate,” Lambrecht said to the group of soon-to-be-citizens. “And that’s one of the things that makes me most sad about this whole thing, is that we’re not able to have those full celebrations.”

All government operations have slowed down since the COVID-19 pandemic started: taxes, getting your Social Security benefits, even the mail. And the process of becoming a U.S. citizen hasn’t been spared.

Pre-COVID, naturalization ceremonies would happen in Colorado libraries, museums and even at Rocky Mountain National Park. As many as 60 people were sworn in together at a time, and the whole ceremony could take close to an hour.

Now it’s all done in a USCIS Field Office room in Centennial, a dozen at a time in about 10 minutes. It might not be ideal, but it does what it’s supposed to do.

Regardless of the circumstances, Shu said she is happy to be here.

“I’ve lived in the U.S. my entire life, and the past year my family and I just felt like maybe it’s time to get our citizenship,” the 23-year-old said. “So yeah, I’m really excited for this to finally be happening.”

Shu and her parents moved from China to the United States when she was 4 years old. Now she’s 23 and geared up to take her Oath of Allegiance: She wore a dusty rose blazer, a tan turtleneck, and a face covering designed with pink and red flowers on a cream backdrop.

Shu is the second member of her family to take the oath. Her mom did it first. Her dad is still in the process. And her little brother was born in the U.S., making him the only citizen in the family for years. But Shu laughed and said he isn’t special anymore.

Her family stayed home for the naturalization ceremony. They wouldn’t be allowed past the lobby downstairs anyway, due to COVID-19 precautions. If you’re not scheduled for naturalization that day, you can’t come in.

Then the time came. Shu and her fellow applicants stood up, raised their hands, and repeated after Lambrecht. After pledging that they “absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty,” Lambrecht congratulated the brand new citizens. And the room broke into clapping and cheers.

Now that Shu is officially an American, she’s got one thing on her mind.

“I’m excited to register to vote for the next election cycle. That’s one of the things I’m most excited to do now that I’m a U.S. citizen,” she said through her mask. “Every four years or every two years for the midterms, everyone gets ready to vote, everyone’s out there voting, and I’m like, ‘I wish I could do it too.’”

And now she can.

For Shu, the day came sooner than she thought it would. She applied for naturalization in September 2020, and was told the process could take up to a year. But five months later she is a new U.S. citizen, waving a tiny American flag.

But not everybody’s journey has been so fast. Aziz Vahobov’s naturalization application has been in limbo for nine months. He said he wants to become a citizen for a lot of reasons. Like Shu, he’s eager to contribute more to his community.

“I don’t want to be the person who’s just making money, feeding kids, just doing my regular routine,” he said. “I like voting in elections, but I cannot use that opportunity because I am not a citizen.”

Vahobov and his wife and two kids moved to Denver from Tajikistan in Central Asia six years ago. When he applied to become a citizen in June 2020, the average processing time for a naturalization application was nine months. Now the USCIS says it can take 13 months. That’s the longest average wait time the office has seen since 2009.

And it’s expensive, too. The whole process has cost Vahobov $725 so far. The USCIS website says the filing fee starts at $640.

USCIS spokesperson Debbie Cannon said the longer wait times are because of the pandemic. She said demand has gone up while capacity has gone down, and that every case is different. The latest available data from USCIS indicates there were 8,537 applicants in the queue to become citizens in Colorado as of September.

Vahobov said he was initially told processing would take three months. Then it was pushed back to the fall. And now, it’s even longer.

It’s been a little stressful for him. He said he wants to go visit family in Tajikistan, but can’t because he’s worried that the opportunity for an interview will come while he’s gone.

In the meantime, Vahobov has been taking this time to study up for his citizenship test. And when the day finally comes to take his oath, he said he’ll be ready.

“We don’t have any exact answer for what and when we can have any change like any interviews or a test,” he said. “I’m just waiting.”