While most people in Colorado live on the Front Range, most of the state’s water is on the West Slope. That’s where the snowpack melts and makes its way into the Colorado River. Much of that water flows to places like Denver through a series of dams, reservoirs, pumps and pipes.

Aurora and Colorado Springs want to bring more of that water to their growing cities, which are the state’s largest after Denver. To do that, they want to dam up Homestake Creek in Eagle County south of Minturn and create a reservoir that could supply water for thousands of new homes.

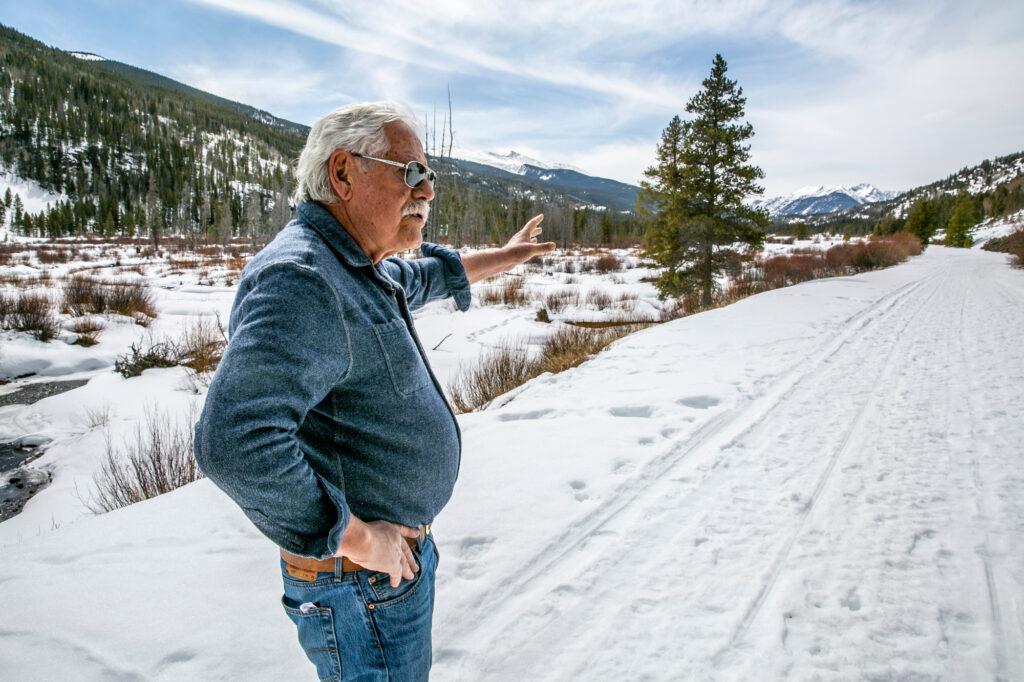

The road that runs along Homestake Creek is still closed for the winter. Jerry Mallett, the founder of Colorado Headwaters, swings his leg over the locked gate and starts walking.

“We're right below where the proposed Whitney Dam would be,” Mallett said, about a mile from the gate. “If we walk up another 150 or 200 yards, we'd be under 250 to 300 feet of water.”

There are a few different spots along the creek that could be the home to the proposed Whitney Reservoir. The largest of the potential sites would hold about 20,000 acre-feet of water.

“Colorado Springs and Aurora got the water right in 1952,” Mallett said. “We just don't think this is the place to take it. There are options downstream.”

Tension between protecting wetlands and securing more water for growing cities

Mallett’s group works to restore and protect areas like this one — a wetland with fox and moose tracks in the snow.

Mallett has fought Aurora and Colorado Springs before. After these cities teamed up and built Homestake Reservoir in the 1960s, they tried to build the reservoir Homestake II. That project was shut down in the 1990s.

“We're not saying you shouldn't grow or that you’ve got to control the population, that’s your issue,” Mallett said. “Ours is protecting the natural resources for other values.”

Aurora and Colorado Springs are working together because they have the same problem: Planners don’t think they have enough water where they are to support the cities’ expected growth. If the cities get their way and dam up Homestake Creek, it would reduce the amount of water that ends up in the Colorado River — which the Front Range and some 40 million people have come to rely on over the decades.

“When the water projects were coming online in the ’50s, ’60s, early ’70s, we considered the West Slope a third-world country. We could mine their resources,” Mallett said.

That’s changed, Mallett said. West Slope communities now see water as a crucial part of keeping their economies alive and now fight for it to stay. Democratic state Sen. Kerry Donovan represents seven counties that include communities like Aspen and Crested Butte. In a letter opposing the project, Donovan wrote that, “she can’t express how sternly the people in her district dislike water diversion projects to the front range.

“West Slope is not in a position I think today where they're going to roll over and say, ‘Fine, we'll lose that water,’” Mallett said. “I think they've got the political clout now, it's a new game.”

If Colorado Springs and Aurora secure permits to build the Whitney Reservoir, it would be the first major trans-mountain water diversion project in decades.

- All That Snow Should Help With Colorado’s Drought, But It’s Still Not Enough For Some Parts Of The State

- Colorado Is Cracking Down On Illegal Ponds In The Arkansas River Basin

- If Ranching Wants To Survive Drought And Other Climate Hassles, It’s Time To Show Soil Some Love

- ‘Greywater’ Could Help Solve Colorado’s Water Problems. Why Aren’t We All Using It?

Environmentalists are concerned about losing these wetlands, which are threatened by climate change. Delia Malone, an ecologist and wildlife chair of the Colorado Chapter of the Sierra Club, said most animals rely on wetlands.

“It's already naturally rare and due to development we've lost even more, further increasing the rarity of that habitat and the essential nature to wildlife,” Malone said.

Malone said the proposed reservoir locations could include areas that are home to fens, a type of wetland that is rare in the arid West and supports plant biodiversity. Fens have layers of peat, require thousands of years to develop and are replenished by groundwater. Fens also trap environmental carbon, improve water quality and store water.

“They are the systems that supply water to streams to enable streams to have a flow,” Malone said. “If we want fish, if we want native species that depend on that water, then we will keep it in the stream.”

Climate change is drying out the Colorado River even as water demands grow

The Colorado River’s flow has dropped about 20 percent since 2000. Research shows that half of that is due to human-caused climate change and that the river’s flow is projected to drop more. Some see that as an argument to keep water in the river. For Aurora and Colorado Springs, climate change makes a reservoir even more critical and would support the cities during drought.

“In the 21st century, new water projects have additional hurdles to deal with,” said Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University.

Udall understands and appreciates Front Range water utilities' mission to supply reliable water to their growing populations, but he said said this new reservoir could face challenges with climate change.

“It’s potential reductions in water for those projects, it’s decreases in water quality,” Udall said. “And then you also have this whole issue around equity of new development, impacting older water projects in Colorado that are already built.”

Colorado and other states are obligated to send a certain amount of water downstream to states like California because of a century-old agreement. As the Colorado River dries with climate change, and more demand is put on the river, Udall said there’s higher risk for what’s called a “compact call,” a provision that gives downstream states like California authority to demand water from upstream states like Colorado for not sending enough water down the Colorado River.

If that happens, Udall said newer Colorado water projects — including the proposed Whitney Reservoir — could have to cut their usage to make sure enough water is sent downstream.

Udall said the best available science is needed to answer the question: Is this water better left in the river or sent to Aurora and Colorado Springs?

“The science really does need to be heard here,” Udall said. “It's somewhat disturbing and is very different from the science that we used in the 20th century to assess the value and benefits of these kinds of projects.”

Officials in Colorado Springs and Aurora declined CPR News’ interview requests.

Before the cities can move towards building the reservoir, the U.S. Forest Service has to sign off on structural testing and surveying which requires drilling test holes in the wetlands. A decision is expected later this month on that permit, which has received more than 500 public comments, with most arguing against the drilling and the project as a whole.