Mandi Corbari was at home in Aurora with her husband in late March when they heard a knock on the door. Corbari was uneasy when the person ignored the doorbell and opened the storm door on their single-family home. Her anxiety also came from some posts she had seen on the social media app Nextdoor.

“The only information I had heard before that was that there were scammers coming door-to-door,” Corbari said.

The post, on March 16, was from a neighbor who said they got visited by someone talking about COVID-19. The post concluded, “You can’t trust nobody these days.”

To be safe, Corbari spoke to the person at her door through the security camera speaker. The person said they were from a group called COVIDCheck Colorado. Corbari still felt wary, and she turned them away.

“He left, but then my husband was like, ‘You need to look that up. They’re probably legit.’”

- STATS: Colorado vaccination stats and other trends

- COVID Vaccines In Colorado: Your always up-to-date guide to finding the info you need

- Statewide rules: The statewide mandates are over. Now it's up to you and your neighbors.

COVIDCheck is a legitimate organization, but misinformation on Nextdoor led a neighborhood astray.

A quick search showed Corbari that COVIDCheck Colorado is indeed a legitimate organization working to provide equitable solutions to the pandemic. But as they were on foot in Northern Aurora, misinformation on Nextdoor made it harder for them to help people get tested or vaccinated.

It’s one example of a national wave of misinformation that has challenged public health efforts in a time of crisis.

"Since when did people go door to door for Covid Check?" one neighbor wrote, describing the person who'd approached as "a young guy with a clipboard."

"Has anyone else had a covid check? You cant [sic] trust nobody these days."

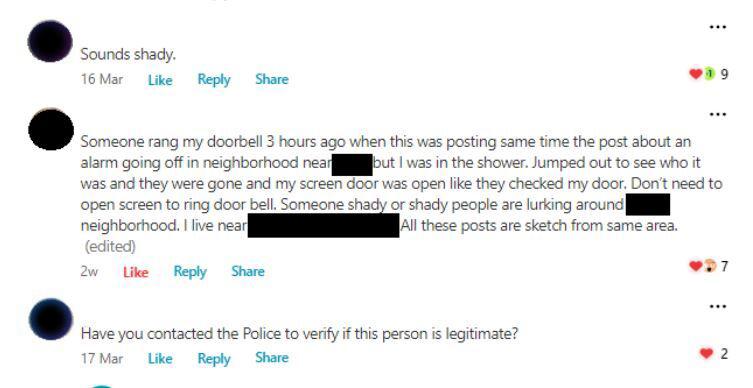

Within just a few days, about 100 people had commented on the post. "He was probably a scammer," one wrote. "Sounds shady," said another. Somebody else described being upset by a person opening their screen door to knock, rather than using the bell. "All these posts are sketch from same area."

Multiple neighbors suggested contacting authorities: "Bet they're casing your house notify the police."

CPR removed the names and specific neighborhoods of the people who commented since they didn’t provide consent to be identified, and Nextdoor is visible only to people in a particular neighborhood.

Online misinformation isn’t a new phenomenon, but it has proliferated in the pandemic.

Dietram Scheufele, a professor of science communication at the University of Wisconsin, explained that social media apps like Nextdoor don’t always promote responsible communication. Rather, they favor user engagement.

“They’re designed to present information in ways that A: fit my priors and B: keep me on the platform as long as possible,” Scheufele said.

He described Nextdoor like a window to the world. Although it allows people to see what’s going on outside, looking through the glass creates the potential for a person’s perspective to be distorted.

“And of course the point is: that’s why we’re all members of Nextdoor, right? We want to be alerted, we want to be warned about things,” Scheufele said.

That’s not to say some people didn’t try to share accurate information. Some neighbors knew it was not a scam attempt, but more adding information to the discussion doesn't necessarily fix misinformation.

“It’s not just about being able to sift through information, but do we actually want to?” Scheufele said.

COVIDCheck Colorado focuses on making sure there's equitable access to COVID-19 information, testing and vaccinations.

The group formed in summer 2020 with an original goal to help get school districts reliable and affordable COVID-19 testing.

As the impact of the pandemic spread, so did their work. Now they are going door-to-door in metro Denver to help people sign up for vaccine appointments. That’s likely what the canvasser was doing at Corbari’s house that day.

COVIDCheck Colorado’s work focuses on neighborhoods where they think they can have the most impact. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that communities of color are at increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19 due to historic inequities in healthcare.

- El Paso County And Servicios de La Raza Tackling Vaccine Equity Through More Targeted Clinics

- Undocumented Immigrants Hard-Hit By The Pandemic Have Few Places To Go For Help. Compañeros In Durango Has Flipped That Around

- In The San Luis Valley, Los Promotores Went Door-To-Door With COVID-19 Information. It Was The Best Way To Get Resources Out

- The Coronavirus Exposed Colorado’s Racial Inequities in Health Care. Community Health Centers Are Trying to Help

Allison Bajracharya, COVIDCheck Colorado’s chief operating officer, said that the group works to combat those inequities.

“So when we’re going door to door we’re trying to prioritize zip codes that are traditionally lower income and have a higher proportion of households of color,” Bajracharya said.

COVIDCheck Colorado is able to provide these opportunities through dozens of partnerships with healthcare providers and other organizations. So far, they’ve provided 4,300 people with vaccine appointments or spots on waitlists by going door-to-door; they also facilitate vaccine appointments online.

Although they understand how showing up unannounced might worry people, they don’t want misinformation to impede their equity work.

“As a parent, I’m also cautious about who’s showing up,” Bajracharya said. “So I think asking for validation on why they’re there and confirmation on what the questions are about is super important.”

COVIDCheck Colorado is one of several organizations focused on equity during the pandemic. Lifespan Local and Mile High United Way have both worked directly with COVIDCheck Colorado, and others like Adelante Community Development work to educate communities about COVID-19 and the vaccines.

At the door, COVIDCheck doesn’t ask for citizenship status, insurance, or Social Security numbers, and they do not ask for money.

When Corbari realized it wasn’t a scam, she went back onto Nextdoor to post what she found out.

“I honestly feel really bad that I sent them away,” Corbari said. “I feel very Nextdoor paranoid now.”

Fortunately, she had already gotten her first round of the vaccine when they visited. But she recognized that her husband probably missed an opportunity to get vaccinated sooner when she sent them away so quickly.