As a social worker with the Denver Public Library, part of Sonia Falcón’s job is to help people in East Denver use government services and benefits. But she’s never seen anything like the unemployment case that has consumed her work since February.

“I would say at minimum 10 hours a week,” Falcón explained. “It's been significant.”

She’s spent all those hours helping one 66-year-old library patron, an out-of-work preschool teacher, with her unemployment benefits. They are trying to navigate the labor department’s new cybersecurity system, which is designed for smartphones and requires multiple forms of current government ID. The preschool teacher has neither.

“She often talks about the fact that her job really revolves around her ability to build relationships,” Falcón said, “and not necessarily with technology. “

The preschool teacher, who couldn’t be reached for comment, is part of a troubling and widespread new example of the digital divide: Increasingly, people need to access and understand digital devices before they can get government help.

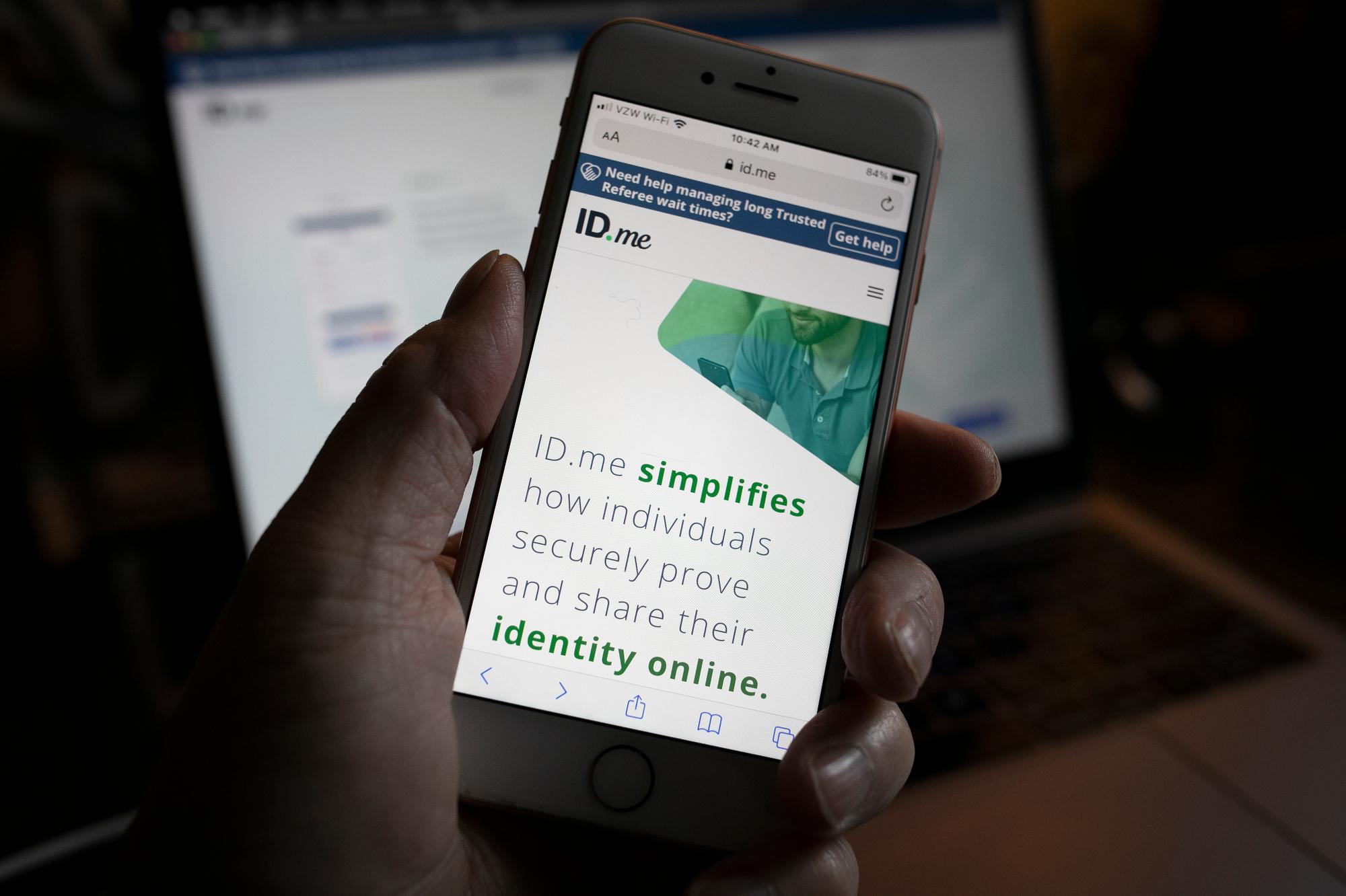

Like dozens of other states, Colorado is turning to new technology to protect its unemployment system from scammers. The labor department recently enlisted a third-party platform, ID.me, to verify people’s identities — a process that requires users to scan their faces with a smartphone’s camera, upload photographs of their IDs and, in some cases, wait for hours for a live video interview.

For Falcón and her client, it’s turned into a nightmare. They’ve spent weeks getting the teacher’s vital documents up to date. Eventually, they’ll have to find a way to have her use a smartphone, perhaps at a recently reopened library branch. Without the verification, the teacher is locked out of her unemployment benefits and has had to visit food banks to survive.

“Not only has her unemployment been withheld from her for various reasons for months, but there's an incredible level of frustration,” Falcón said.

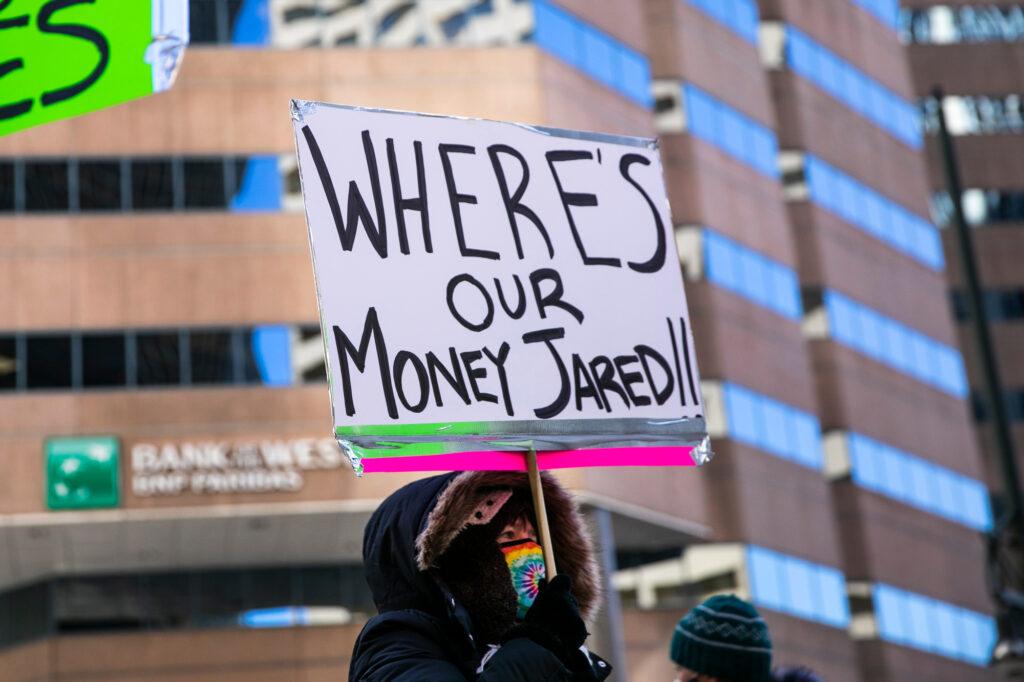

Collateral damage in a war against scammers

Until the pandemic, it was simpler to get unemployment benefits in Colorado and elsewhere. State security systems generally asked people to fill out a form with their personal information — facts like their date of birth and their social security number — to prove who they were. That was easy enough for many people.

But the last year has revealed that approach to be obsolete as scammers have used hordes of stolen identities to raid unemployment systems across the country, syphoning off hundreds of millions of dollars in fraudulent claims. In response, Colorado hired ID.me, which uses facial recognition to match people to their government documents, among other strategies. Other states are using other vendors and methods — a necessary step, they said, to stop the bleeding.

Colorado first introduced ID.me in January for some users, and it will soon require all of its 200,000-plus unemployment recipients to use the platform. It’s one of 22 states using the system for unemployment benefits, with more on the way, according to ID.me.

Like previous changes to the UI system during the pandemic, the new technology has caused a wave of confusion and complaints about overloaded help lines. But this latest change is hitting certain groups particularly hard.

For example, a smartphone is mandatory for ID.me’s main automated process, according to the state labor department. But about 15 percent of the U.S. population doesn’t own a smartphone, a group that disproportionately includes older adults, Black and Latino people, people with less income and those in rural areas.

“I’m shocked that they need to have a smartphone — not just have a smartphone, but they need to use facial recognition,” said Myra Nagy, a client of Colorado Coalition for the Homeless who helps others with technology. “They’re not going to know what that means or how to use it.”

People who don’t have a smartphone can go through a video interview process instead, according to ID.me, but that requires a computer with a webcam and, often, an hours-long wait. The state also is offering in-person appointments and other help with ID.me through its call center at 303-536-5615.

Other challenges for users can include a lack of reliable internet access or simply a lack of familiarity with technology. In Divide, Colorado, 75-year-old Ingrid Jonsson spent two days wrestling with the service, trying and failing 60 times to take an acceptable photo of herself with her older smartphone.

“The instructions weren't very clear, so I was probably doing it wrong. And it's not a very good camera,” said Jonsson. “And it just -- they wouldn't accept it, you know?”

She eventually cleared ID.me, but only after waiting in a virtual line for seven hours for a video interview — which about 16 percent of Colorado users must do. Maintaining a solid internet connection for so long can be challenging, especially for those in rural areas or with low data caps, said Desiree Marceau of Crestone, who was glued to her phone for hours as she tried to get through the queue.

Getting through ID.me doesn’t always solve people’s problems, either. Ingrid Jonsson’s account is still in limbo due to a separate issue with the state system. Meanwhile, she’s cut back to two meals a day and has survived from reverse mortgage payments on her rural home, she said. She fears losing the property — four acres with a view of Pikes Peak — if the problems aren’t resolved soon.

80% approved, 20% rejected

The people struggling now to verify their identities are collateral damage in a cybersecurity war between state unemployment administrators and faceless legions of would-be scammers.

“Right now there's two sides of the current challenge,” said Blake Hall, CEO of ID.me. “We want everyone who's eligible for unemployment benefits to get access to them. And, at the same time we're fighting nation-states and organized crime rings. And the country’s already lost hundreds of billions of dollars to those actors.”

The company acknowledges its process is especially difficult to navigate for people who don’t have experience with technology.

So far, the platform has approved about 80 percent of the Coloradans who attempt the process, state officials said — with about 164,000 total verified so far, and roughly 40,000 rejected. While some users described long, frustrating waits, others found the process fast and convenient.

The introduction of the system has contributed to a recent decline in unemployment beneficiaries, according to CDLE, from a recent peak of 220,000 in late March to about 171,000 last week. But it’s impossible to say how many of the rejected claims were from scammers and how many were from legitimate users who couldn’t complete the process. Overall, state officials believe that ID.me and other defenses have stopped hundreds of millions of dollars in fraud.

Hundreds of thousands of additional claimants haven't responded to CDLE’s orders to use ID.me, likely because the claims were fraudulent, CDLE officials said.

What to do if you’re unable complete the ID.me process:

Call the state help center at 303-536-5615. Agents can offer assistance, refer you to ID.me's support team or, in some cases, book an in-person appointment for users who don't have the right technology. The state also offers ID.me tips on its website.

Hall and state officials say they’re working to make the system more accessible. ID.me plans to create 500 physical outposts across the country where people can get verified in person. Those will open June 1. The company also is developing a version of its face-scanning technology that will work with webcams on computers, according to CDLE.

Meanwhile, state officials say that their help agents are doing all they can — including booking in-person appointments and referring people to ID.me’s support team.

“We ask them to call the call center, so we can figure out what they need to do and get through the process,” said Phil Spesshardt, benefit services manager for CDLE. The digital divide, he said, is “an area that we will continue to work on. ID.me is continuing to try to work in this area.”

Sign of a much larger problem

When I invited people to email me about their experiences ID.me, more than 70 responded. Their stories detailed a range of struggles with the technology.

Elmo Griego is a laid-off construction worker living in a rural New Mexico village where he relies on cellular data for his internet. He was collecting unemployment from Colorado because he had worked here. After he got a verification notice, he was unable to complete the ID.me process — so his daughter drove 100 miles to help him.

“You need to be able to take into consideration that not everybody can be able to afford the internet or a computer or things like that,” said Griego, who’s in his 60s. “People are spending their money for food, shelter and what have you.”

These new effects of the digital divide extend far beyond one company’s technology. The unemployment system was already a complex nightmare for countless users. It’s often difficult to tell whether an account is disabled because of a glitch or one of the countless rules governing the program. Meanwhile, other services like the DMV temporarily shifted to a largely online presence during the pandemic.

“The change is that it’s impossible to talk to a human being,” said Denise Beasley, who helps formerly homeless people with their government services for Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.

One of her clients, she said, is an older man who lost his manual labor job. He was unable to navigate even the basics of the state’s regular unemployment site, since he doesn’t know how to use email. So he tried to get a job at Amazon, passing an initial computer-based test before, eventually, being defeated by the company’s heavily automated bureaucracy. For now, he’s subsisting on food stamps.

Beasley has worked in social services for more than 30 years, and she prides herself on never giving up, even when her clients feel defeated. But as technological challenges mount, she’s starting to feel overwhelmed.

“It means that we just give up,” she said ruefully. “Many times now, I am the one that is giving up.”