The Arvada mother said by the time she called the police to escort her 16 year-old-son to the emergency room against his will, he’d already kicked 20 holes in the walls of their home.

“There was nothing we could do. Like, it was completely game over,” said Cynthia.

Cynthia said her son had always had a temper, but he had begun to frequently go from zero to 60 over the tiniest things. One of the lowest points was when he threw a rock at her, narrowly missing her head. That’s when she called 911.

“All those who saw him come in (to the ER) thought that it was either meth or heroin or some sort of high dosage of opioid,” she said.

But what doctors found in her son's system was THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis. He had been taking it in highly concentrated doses, up to 95 percent purity. From that point, Cynthia said their lives were “complete hell” as they waited for a spot to open in a rehab program.

“It was all about confiscating dab pens, cartridges, wax canisters, concentrate canisters from him,” Cynthia said. She asked CPR to not use her last name in this story and declined to make her son available for an interview; she said she wants to protect his privacy and keep his recovery on track.

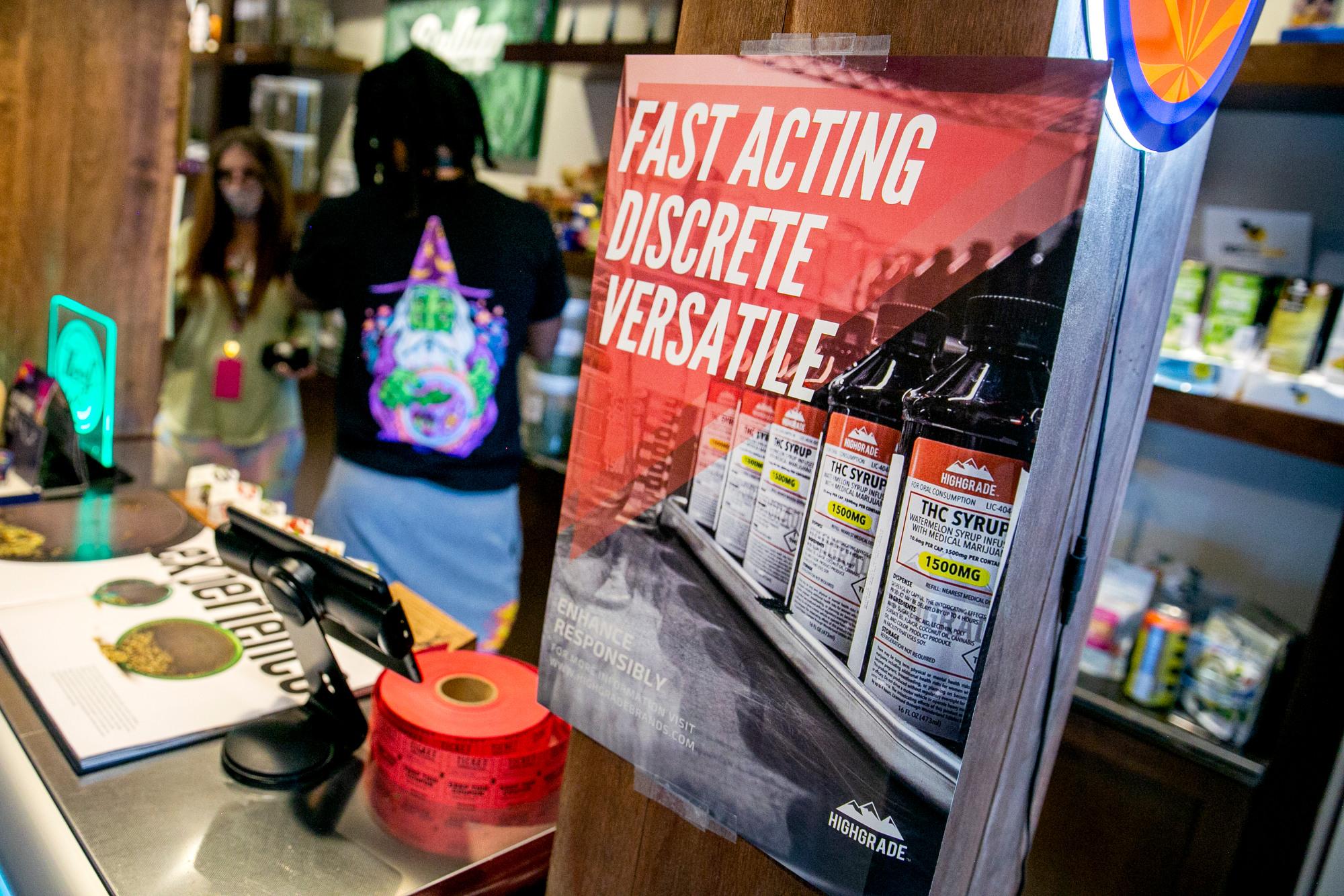

These stronger forms of marijuana are extracted from the plant and consumed in a number of different forms, and they have become more popular and widespread since legalization. THC levels in products based on concentrate can be up to nine times higher than in cannabis flower, which typically has a range of about 10 to 30 percent THC.

“These high-potency products haven't really been addressed from a public health perspective,” said Dr. Sam Wang, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Colorado. He helped author a state health department study on high potency marijuana which analyzed existing research and available data.

Wang said recent health surveys show that there aren’t more young people using cannabis, but those who do, use it more frequently and are increasingly using methods — like dabbing and vape pens — associated with higher concentration products. Findings like that are leading to concern by Wang and others about the potential for lasting psychological damage to young users; although studies have not established a causal link between marijuana use and psychological impacts.

“There's moderate evidence that individuals who use marijuana with THC concentrations of greater 10 percent are more likely than non-users to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, including specifically schizophrenia,” said Wang. “THC toxification can also lead to acute psychotic symptoms and that's worse at higher THC doses.”

Agreement on the problem, but not on the solution

Colorado already limits the amount of THC in marijuana edibles and some advocates would like to see that policy extended to all products.

Dawn Reinfeld is the co-founder of Blue Rising Together, a group that’s been pushing for lawmakers to introduce a bill this session to cap THC at 15 percent. “As we look nationally to legalize marijuana, we feel like we have to tell the truth in Colorado about what has worked and what is not working.”

There were short-lived discussions around the start of the legislative session about a THC cap. But such a hard limit doesn’t appear to be on the table this year, after the industry and others raised concerns about the lack of scientific data about what an appropriate upper limit might be.

“I think using arbitrary numbers is difficult,” said Wang. “But at the same time, time is of essence. So I don't think anyone wants to wait 10, 20 years to do long-term research to figure out what the right number is.”

Another hurdle for crafting policy changes is that there’s little tracking of things like how often THC-consumption leads to hospitalization or other health conditions, making it harder to agree on the scope of the problem.

According to figures from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, from January 2017 to June, 2020, Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety, the state’s poison control center, recorded 32 calls about exposure to concentrates in teens aged 13 to 20.

Colorado isn’t alone in considering limits on cannabis potency. Four states have recently introduced bills to cap THC, but so far none gained traction. Currently Vermont is the only state with a limit in place.

Washington state Rep. Lauren Davis, a Democrat, has unsuccessfully introduced a 10 percent THC cap twice in the last two years. But she said she did make some headway this session, getting her colleagues to include a half million dollars in the state budget to fund more research into high potency marijuana and come up with policy solutions.

“How do you thread the needle here?” Davis said. “Now that Pandora's box has been opened, what do you do?”

In Colorado, Democratic Speaker of the House Alec Garnett is working behind the scenes to craft regulatory changes that lawmakers might be willing to act on now. He estimates his central Denver district has more dispensaries than coffee shops.

Garnett said Colorado needs to first recognize that teenagers are getting more access to high potency products than ever before.

“Within five years, if we don't do something about it, it's going to be an issue that every single American knows about similar to the opioid epidemic.”

He said a good first step would be to increase taxes on the most potent products, providing money for research to better understand the health impacts. In Colorado, recreational buyers have to be at least 21 years old. But Garnett is most worried about 18- to 21-year-olds with medical marijuana cards — who may be buying and reselling to younger teens. Garnett also wants to see a limit on how much product they can purchase.

He hopes to set up a statewide tracking system to determine when people reach the daily legal limit for purchases. Some stores have internal tracking systems, but those are easy to avoid by buying from different dispensaries.

“People shouldn’t be able to go and buy 40 grams a day of the highest potency products on the marketplace, because there's no logical reason that you would actually need that,” he said.

‘I want people coming in who are of age’

Representatives of the cannabis industry say there’s broad agreement that they don’t want underage kids getting their products. But they argue that a cap would limit options for legitimate adult consumers without solving the problem of youth use.

Peter Marcus is with Terrapin, a cannabis company based in Boulder with six dispensaries in Colorado. He said the industry is simply responding to market desires and what consumers are asking for.

“These products, they didn’t come out of nowhere. These products were in demand. And for responsible adults, they should be able to make the decisions for themselves on which products they want to use,” he said.

Marcus said a low THC cap for flower and concentrates would put the vast majority of Colorado’s cannabis industry out of business.

“They don't understand that it is literally impossible for us currently, nor would we want to, genetically modify our plants to reach some arbitrary number that the legislature pulls out of thin air.”

Sherard Rogers owns the RollUp dispensary in Denver. He’s a father of three and splits his time between Florida and Colorado. He said the industry and his own business are shifting more to concentrates because they are popular with customers and their purity makes them beneficial for certain health conditions.

“They're a cleaner product. They don't have the smell that a typical cannabis product would have. It’s cheaper, more dialed in,” he said.

Rogers points out that marijuana is already heavily regulated in Colorado, with protections in place to try to keep it out of the hands of children. The state requires ID checks and video surveillance.

“This is going to sound terrible... but aren't parents supposed to have the best interest of their children and be the gatekeepers for their children?” Rogers said. “It’s not like we’re selling a cannabis product out the back door. I want people coming in who are of age and are using it for the right purposes.”

Some in the cannabis industry said they would support the proposals Garnett is talking about, like expanded tracking, more funding for research, and even higher taxes on some products. Rogers, though, warns that raising taxes would especially hurt small business owners like himself, who already struggle to keep afloat.

“You don't have any tax deductible expenses on the store side because it is not federally legalized. If they want to have us go out of business, then continue to increase the taxes.”

The state already levies an extra 15 percent sales tax on recreational cannabis, on top of the normal sales tax, and many local governments also charge additional sales tax.

Any tax increase for concentrated products would need to be referred to the ballot and approved by voters this fall.

The governor’s influence

The industry has one very strong ally at the state capitol: Democratic Governor Jared Polis. He has been a staunch advocate for ca legalization since his days in Congress and is not expected to sign any legislation if the industry isn’t on board.

“I take seriously the voter mandate; which is, ‘regulate marijuana like alcohol’,” Polis told CPR earlier this month. And that, he said, means Colorado should do more to prevent youth from gaining access to both substances. “It's a real problem, it needs to be solved.”

For Arvada mother Cynthia, whose son ended up in the hospital and then rehab, the right course isn’t clear. She voted to legalize cannabis, but never expected it to end up like this for her family.

Her son recently started attending a recovery high school. She said when she picks him up they can smell marijuana in the air outside, and on their drive home, they pass at least ten dispensaries.

“As a parent, it's really difficult to know what I would like to see changed,” she said. “What I can tell you is I'm not so sure we should have a dispensary on every street corner in Colorado.”

Yet with only six weeks left in the legislative session, those who feel an urgency around the situation may have to wait even longer for significant official action.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to reflect a source's retroactive request for partial anonymity to more fully protect the identity of her son.