Amtrak’s California Zephyr glides nearly 2,500 miles between Chicago and the San Francisco Bay Area. Colorado is right in the middle, with train stations nestled in mountains, deserts and plains.

Train ridership plunged earlier in the pandemic, prompting Amtrak to cut schedules on long-haul routes to just three days a week.

But now, Amtrak is phasing daily long-haul service back in across the country, which seemed like the perfect excuse (ahem, I mean news hook) to take the California Zephyr all the way across Colorado. The truth is, I just love riding the train.

The plan was to travel from the state’s most western stop, Grand Junction, to its farthest east, Fort Morgan, about 80 miles past Denver, and talk to folks along the way.

But between social distancing and masks, plus the general pandemic exhaustion a lot of us are carrying around, I had no idea if the breezy train conversations of my memory were even possible. Did people still want to open up to a stranger?

I ended up meeting Jessica Theisen before the train even left the station. Outgoing and carrying a longboard, told me she was returning to Denver from Utah, where she’d celebrated her 21st birthday with her dad. When an announcement about the snack bar played over the loudspeaker, her eyes lit up.

“I can buy wine now!” she said, both surprised and stoked.

As we settled into the viewing car — the absolute best part of the train, by the way — she explained that, yeah, she could have gotten to Utah faster by driving.

“But I was like, I really want to take the train. I haven't been on the train since I was 7!”

That’s when Theisen’s grandmother took her on the Zephyr to Glenwood Springs. She did that with each of her grandkids, all 30 of them. Her grandma loved trains.

“And when I'm on the train, it's like, she's watching me, you know?” Theisen said.

We headed east, past the small town of Palisade, a conveyor belt of sun-baked high desert floating past.

The next stop was Glenwood Springs, its red-brick station cute as a button, mountains nearly hugging it, a hot springs pool beckoning nearby.

Then it was into Glenwood Canyon, whose lofty cliffs looming over the Colorado River actually inspired the first viewing cars on this route. We diverged from the highway and went through more canyons, far from any town.

Vicki Breton, retired and on her way to New Orleans, looked up from her knitting at the plunging granite walls, hundreds of feet high.

“It’s unbelievable. I've never seen anything like it,” she said. “Looks like a cathedral at the top of a mountain. Just beautiful stone formations.”

She said a prayer to herself as we went through, with the hopes that when she returned home to Oakland, she’d be able to recite it again and be transported right back, the image forever stored in her head.

“It’s kind of like praising whoever made all of this to me,” she said. “It's just God showing what he can do on earth.”

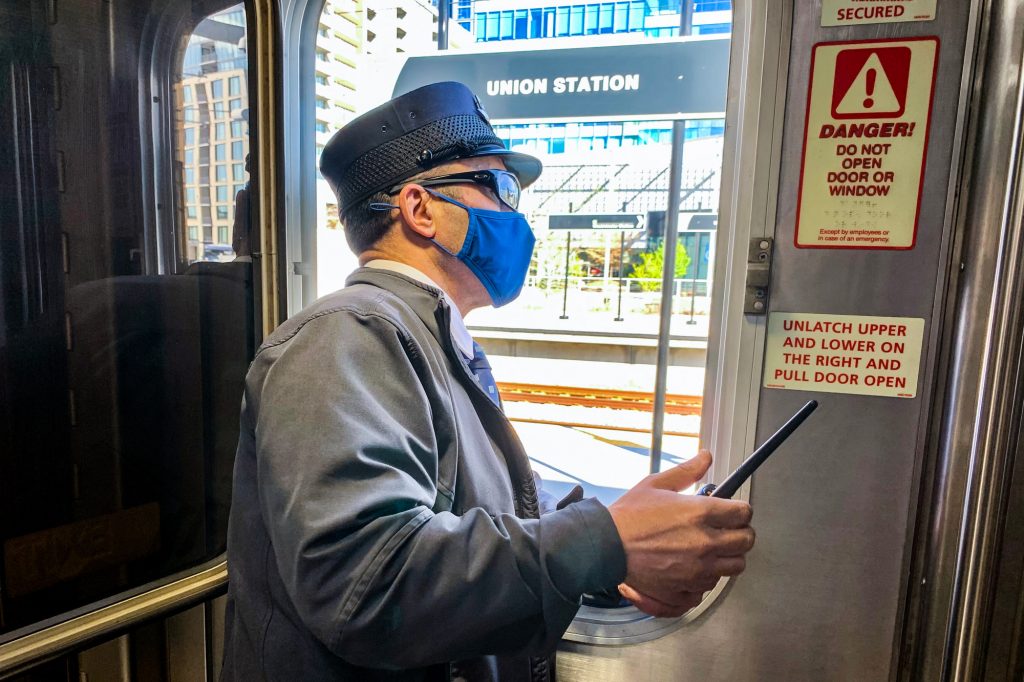

A few tables away, Conductor Chris Lopez — Conductor Chris, everyone calls him — had set up shop. He’s the kind of guy who carries around special stones to give certain passengers and is happy to talk philosophy when the mood is right. He was waiting on answers to a word problem he’d announced over the speaker, trying to get people to guess the arrival time of the Zephyr at the end of the line in California if it kept up a steady speed.

One by one, passengers kept walking up, only to be told they were “so close” or should “keep trying.” Everyone got three shots.

Carla Baker, from Kentucky, was on her last guess, and only needed to change one tiny thing about her answer.

Conductor Chris tapped out a drum roll on the table.

“Survey says ….” he prompted.

“PM!” Baker declared, sounding confident.

The conductor let out a happy holler: “Winner, winner, chicken dinner!”

For her correct answer, Baker got a cardboard conductor hat she thought her grandson would love, and Conductor Chris got what he wanted: to interact with passengers. There’s no Wi-Fi on the train and for long stretches, no cell service either. That’s when the “Conductor Challenge” comes in, which gives people something to do, but also a way to connect.

“As you've noticed, when I talk to people, it's not about the destination, it is about the journey,” Conductor Chris said, his voice full of belief. “So we're just trying to find a way to maximize people's experience on this journey.”

And a journey by train is like nothing else.

As we moved through the mountains, Tessa Heeren could see dramatic, snow-capped peaks off in the distance. She enjoys the “grand sights,” the train offers, but is also into the train’s more ordinary views, the intimate window it gives her into communities along the tracks.

“Like the back of people's houses, backyards, little bars, little towns, little junkyards, graffiti,” she said, a small community moving past her window.

Heeren has been traveling by train for months, working remotely and stopping in various places as she slowly heads home to Iowa. She’s gone from being someone who did not really take trains to a bonafide train person.

“It’s a special little subculture, I think,” she said

And that collection of train devotees includes passengers and crew. Train attendant Tim Noel first crossed Colorado as a kid on what was then known as the Rio Grande Zephyr. He remembers telling his parents that he would “scrub the toilets” on the train if the railroad would just give him a job.

“Well, be careful what you ask for,” he said with a laugh. “Cause that’s what I do.”

It’s just one aspect of his job, which keeps him on the train for six days straight. But Noel gives thanks for this life every morning. He brought up the Mark Twain quote about if you find a job you enjoy, “You will never have to work a day in your life.”

“I've been here almost 28 years,” Noel said. “Haven't worked a day yet.”

The train descended the mountains and hissed into Denver’s Union Station by evening. A crowd of passengers got off, quickly replaced by just as many people getting on. After the windows were washed, the bags taken off and several passenger cigarettes smoked, we continued on, into more than an hour of flat land.

Finally, there it was: Fort Morgan. We arrived at its darkened, Americana streets more than 10 hours after we left Grand Junction.

I got back on the train just about the time the sun was rising the next morning. It was the same stunning trip in reverse. When we made it back to the Colorado River, we were treated to an unofficial California Zephyr tradition: getting mooned by boaters. One raft presented three or four pale butts in our direction.

This was a huge hit with the viewing car, where people laughed and clapped.

As I got closer and closer to home, I thought about how the train is one of the few spaces in life where you get hours free of obligation, where you get time to just be. I was delighting in it. So was Maggie Tracey, who sat nearby.

“Like, I brought books along, I brought work, and I haven't done any of it,” she said, starting to laugh. “All I do is sit and look out the window.”

Tracey and her husband were headed home to Nevada after vacationing across remote spots in the West. They’re both in their 70s, but this was their first-ever overnight train experience.

“Yeah, I’m sold on it,” she said, with more pleased laughter.

Soon they’d invited me to stay with them at their place sometime, and I’d invited them to stay at mine. All around us, I could hear similar conversations: People sharing stories and laughs and email addresses, promises to hang out again. It felt like we were all about to leave summer camp and head back to real life. I don’t think I was the only one who wanted to hold on to this other world a little longer.

When we pulled into Grand Junction, we were about an hour late, but no one seemed to mind. That is not what taking the train is all about.