One hundred years ago raging waters unleashed by torrential rains and snowmelt broke through Pueblo’s Arkansas River levees, causing one of the deadliest and most destructive floods in Colorado’s history.

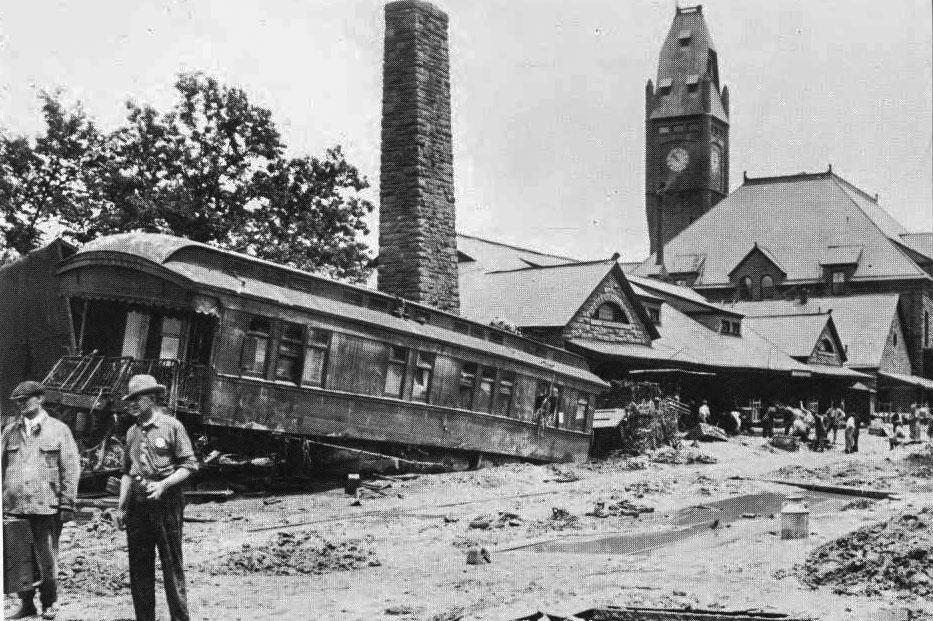

Local historian John Korber’s father worked for the railroad back then. Korber wasn't born yet, but he tells his family’s story of what happened on the evening of June 3, 1921 when his dad finished his shift.

“He was on one of the last trains that came in from Salida,” Korber said, “and when he arrived in Pueblo the water was already up almost knee deep.”

His father waded out of the station and made his way home, up on a nearby bluff.

“My mother had been keeping track of things,” Korber said. “They were forecasting more wet weather and (she) said maybe go down and get your father and bring him up to the house.”

Korber's grandfather, who lived near the river, chose to stay put.

“My grandfather apparently was a stubborn old German. And he says no, sir, I'm not leaving my house. I've been through rainstorms before,” Korber said.

“One of the things the flood victims all said is that the sounds haunted them"

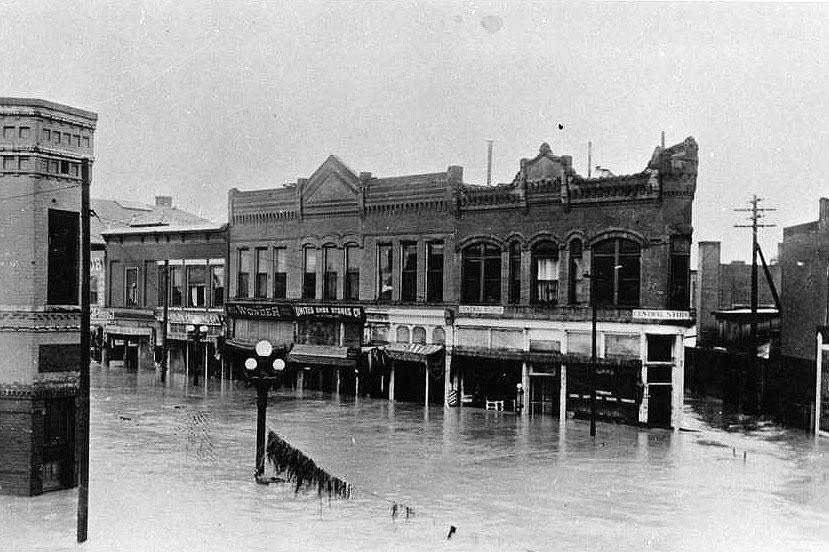

Within hours the river overtopped the levees, flooding into the business district. People ran for higher ground, climbed to the upper floors of buildings or into trees. Lightning flashed and the rain continued to pour down.

Peggy Willcox helped research the Pueblo County Historical Society’s book “Mad River.” She says the raging waters carried debris including boxcars, automobiles and drowning livestock.

“One of the things the flood victims all said is that the sounds haunted them,” Willcox said. “There was lots of crashing of buildings falling and people calling for help. The sounds of that night were horrendous.”

At its highest, the water surged to more than 14 feet deep in some places. Fires ignited in lumber yards launching masses of flaming timbers into the roiling dark deluge.

“Those fires...added to the terror for people,” Willcox said. “Because you can imagine, here's this...burning lumber that just bounces off one thing that it sets on fire and bounces into another.”

Initial fatality estimates were around 500 — but "there is no way to know"

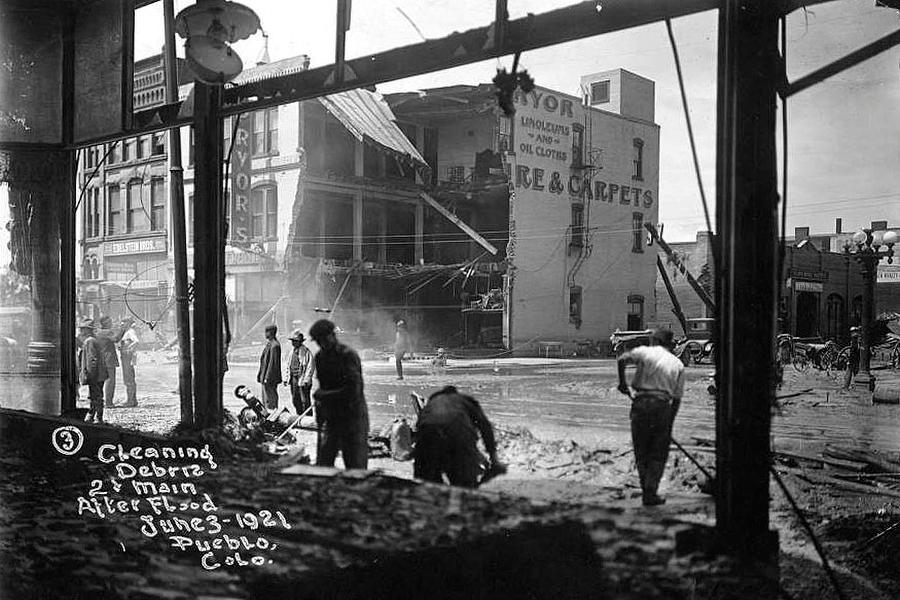

The city awoke the next morning to find houses ripped from foundations, shops gutted, bridges torn out and twisted railroad tracks, according to Willcox. The water was still five feet deep in places. Elsewhere, mud piled up, dotted with animal carcasses.

As for the human death toll, Willcox said the initial estimates were around 500 fatalities, but victims may have been washed down river, buried in mud or were just never accounted for.

“We will never know how many people perished,” Willcox said. ”There is no way to know.”

The local mortuary couldn’t handle the huge number of bodies. They lined the corpses along Main Street so families could look for loved ones. John Korber’s grandfather was among them, identifiable only by the ring he wore. Floodwaters had dragged his body a half a mile into a damaged furniture store.

Although power and phones were out, officials sent a telegram north, most likely from the steel mill’s offices in an area outside the flood zone.

“City officials tried to immediately get a handle on the scope of the flood,” Willcox said. They established curfews, emergency food plans, shelters and more. The rains continued, though not as heavily. Willcox said within a few days a work order was issued for able-bodied men.

“No idlers would be allowed. Either you volunteered to go work for 43 cents an hour, or they arrested you and you work for free,” she said.

Pueblo’s recovery and rebuilding in the flood's aftermath

It was slow going in the thick mud and debris. Eventually the Army arrived with heavy equipment. Relief donations rolled in from around the nation. Property damage was estimated to be in the hundreds of millions in today's dollars.

“The question is not just how much it costs to repair a single structure,” CSU-Pueblo history professor Jonathan Rees said. “But what you need to do to prevent this from happening again, and what you're not doing because you're spending all that money to repair the damage....When you include those opportunity costs, it's incalculable. It really comes to define I think the entire future of the town from that point on.”

Footing the bill for updating the city’s flood protection fell on Puebloans. Engineers moved the Arkansas River channel about a third of a mile away from its original course where the Historic Arkansas Riverwalk of Pueblo, or HARP, is now and built a massive new three-mile long levee as well as a dam upstream to help control water flow.

Maria Sanchez-Tucker grew up in Pueblo and used to run the Bessemer Historical Society and manage special collections at the library.

“It's sort of in our genetic makeup if you're from Pueblo,” she said, “because people who have had generations of family members remember what took place. It was an awful experience for many people to go through. But it was also one that shows resilience and how we can come together to support each other during a crisis.”

Puebloans continued to work for a better future by turning the abandoned former river channel, once the scene of horrific devastation, into an asset. Now tourist excursion boats ply the HARP’s peaceful waterway that meanders through downtown Pueblo.

CPR News visuals editor Hart Van Denburg contributed to this report.