It was March 6, 2021. Bryan Raymond lay in an ICU at UCHealth in Aurora, sustained by two forms of life support. A surgeon walked into the room and delivered good news: the donor’s lungs looked good. The transplant was on.

Raymond and his wife, Trinity Raymond, were elated — and scared.

“I remember looking at Trinity and saying ‘I love you’ and thinking that was the last time I was going to see her,” Bryan Raymond said. “But, you know, I knew I had God on my side and you know it was either his time to call me home or he has a bigger plan for me.”

A year and a day after Colorado officially recorded its first case of the coronavirus, Bryan Raymond, 37, received the state’s first COVID-19-related lung transplant.

Last week, Trinity Raymond finally got to pack the couple’s car and they headed home from Colorado to tiny Malta, Montana. On Father’s Day, the whole family was under the same roof for the first time in six months.

'I just didn’t feel right...'

The Raymonds’ story began in Malta, Montana, near the Canadian border, where they met as teenagers.

“We have one chain restaurant. That's the Dairy Queen,” Bryan said. “We do have a front street, has a couple of businesses on it. A couple of restaurants. There's one blinking yellow light to the underpass.”

The Raymonds are raising four kids, Ryder, Renzey, Raegyn and Rivyr, ages 3 to 15. Trinity teaches elementary school. Bryan was a street maintenance worker, driving heavy equipment and hefting truck-sized tires around the shop. In his spare time, he refereed youth sports.

The Raymonds say they took what seemed like the right precautions against the virus. They masked up when they went to the grocery store; they stayed in more than they normally would. But both were still working.

“We didn’t take it lightly,” Trinity said. “I’m sure we could have done better, but we also — I don’t think we could have grasped, I don’t think we ever would have imagined it being this bad for us.”

That is, they didn’t imagine until a few days after Thanksgiving last year, when Bryan suddenly got sick.

“We were hauling gravel that day and I just didn't feel right. You know, my throat was kind of sore and I didn't think, you know, I thought maybe I was getting a cold or something. Well, we had gotten back to the shop that night and I was just kind of sitting there and I could feel myself getting a fever.”

The next day he got his test results back. He was positive for COVID-19. He stayed home, expecting to recuperate, but things got worse. On Dec. 9, when Bryan checked his blood-oxygen level on a pulse oximeter, the numbers were so low he thought it was a mistake. Trinity’s aunt, a nurse, came over, double-checked and drove him straight to the hospital.

That very night, Bryan was flown to a much bigger hospital in Billings, Montana. Trinity, stymied by hospital infection protocols that would keep her from Bryan’s side repeatedly during the ordeal, stayed behind with the kids.

'The whole hope was just to give his lungs time to rest and to heal'

At first, the Raymonds thought Bryan just needed more advanced care and a chance for his lungs to get better. But on Dec. 17, Trinity got a 3 a.m. call from a nurse saying he needed to be on a ventilator.

“She put me on speakerphone. So she's in his room talking and I can hear her kind of saying stuff to him. And I said, ‘What is he saying?’ And she said, ‘He's just telling me no, no, he doesn't want that.’ And at that time I remember thinking like, I hope they don't give him a choice. Like, yes, that's what he's getting right now.”

A couple of hours later, another call. This time the doctors needed permission to use an additional device, called an ECMO — that’s extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In essence, Bryan’s blood was pumped outside his body, put through a machine that reoxygenated it, and then put back in his body.

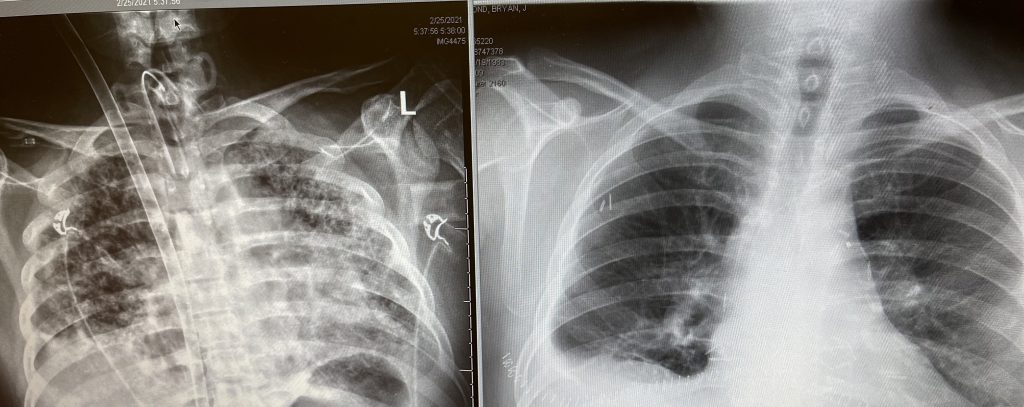

Days and weeks went by. By then it was clear that Bryan’s lungs wouldn’t work forever without the machines and weren’t likely to recover. The word transplant surfaced and the search for a hospital that could do that began. But there were two problems: For one, hospitals across the country were crammed with other COVID patients.

Second, Bryan had Multiple Sclerosis, an autoimmune disease. It hadn’t hampered his daily activities — heavy physical labor and running around sports fields chasing after kids — but some hospitals said it disqualified him for a transplant.

As Bryan languished in Billings, he and his family did frequent video chats, Trinity said.

“So Christmas, I FaceTimed him so he could watch the kids open their gifts. I tried to keep things as normal as I could for the kids, but it was hard.”

A few days later, Trinity went down to Billings for a short stay. She was making plans to go back to Malta when a doctor stopped her.

“The doctor said, ‘We’re going to encourage you to stay,’ and so I knew it was bad that he said that.’’

Reading between the lines, Trinity thought the doctors were telling her Bryan was going to die.

But he hung on. Finally, there was a phone call from the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora. They would accept him as a patient. But there were still no guarantees he could actually get the transplant, or that it would be successful. Bryan had a lot of work to do.

'We know we’ve got to get him stronger or the transplant isn’t an option'

When he arrived in Colorado in early January, Bryan’s condition had deteriorated even further. For weeks, he lay heavily sedated, virtually unresponsive.

He had wasted away in bed. His diseased lungs hadn’t worked on their own since December so the muscles in his diaphragm were shot. He was so weak he couldn’t lift his head. If doctors were to declare him eligible for a transplant he’d need to be much stronger.

That meant endless rounds of physical therapy. Gradually, Bryan could sit up, then stand, then walk a little bit. A crowd of people surrounded him at every step, keeping the ventilator and the ECMO machine working, guiding the IV poles and propping up their patient. Finally, he was strong enough for a transplant.

Before long, a donor was identified. The Raymonds don’t know much about the person, even now. They only know the person was in Colorado.

Raymond was wheeled into surgery on the afternoon of March 6.

The 'Unfortunate Sweet Spot'

Surgeon Rob Meguid figures he’s performed 150 lung transplants in his career. He didn’t meet the Raymonds until the day of the operation, but word of Bryan’s case had gotten around. Knowing he might be called upon to perform the transplant, Meguid began consulting with other physicians around the country who’d done the surgery on COVID-19 patients.

Hours before the operation, Meguid walked into the Raymonds’ room, introduced himself and told them how the surgery would go.

“Bryan was very sick,” Meguid said. “If he hadn't had a lung transplantation, he probably would not have survived significantly longer.”

That said, Bryan was in an “unfortunate sweet spot,” to become the state’s first COVID-19 related lung transplant. Previous patients “weren’t sick enough or they were too sick and died,” Meguid said. “That ability to engage in physical therapy, that set him apart from the people in the rooms next to him.”

Bryan’s Multiple Sclerosis, Meguid said, may — or may not — have made his disease more severe but it didn’t impact the transplant decision or his recovery.

“It may have made him more susceptible to developing a more severe COVID infection ... When I met him, if I hadn't read that in this chart, I would not have known he had that. And in taking care of him subsequently, it's never been an issue. So it's hard for me to ascribe that to the cause of why he developed such a bad response to COVID.”

The lesson of Bryan’s case, the doctor said, is that “for severe COVID-19 patients there’s no great treatment.” The disease can cause irreversible scarring, sometimes leaving transplant as the only option.

“But it’s not available to everyone based on their (physical) function and their ability and it’s not available at every hospital, so it’s not a solution we as a society should rely on.”

Meguid said he expects he’ll be doing more transplants in the future as COVID-19 “long-haulers” have deteriorating lung function.

'Smell The Roses, Blow-Out-The-Candle Breaths'

The surgery lasted eight hours. At last, though, Bryan was on a slow road to recovery. He had to learn to breathe with his new lungs. Trinity calls the technique “smell the roses, blow out the candle breaths.”

Bryan uses the more formal name “pursed-lip breathing … so you breathe through your nose and then you exhale out of your mouth. And the exhale needs to be longer than the inhale.”

In their downtime in the hospital, the Raymonds sustained themselves with prayer — and with music. A custodian “would sing every time that she came in and she had the most beautiful voice,” Bryan said.

“I can still hear her today.”

After more rehabilitation, Bryan left the hospital and went to live with Trinity at a place called Harlow House — a single-family home in a quiet Aurora neighborhood that serves as temporary housing for patients and their families. Their kids stayed with Trinity’s parents in Montana through this time.

Bryan was back and forth to the hospital a lot for medical appointments and checkups and he started to get back in the real world: “I actually jogged for five minutes.”

And then the Raymonds’ four kids came down for Memorial Day weekend.

“It was just hugs and tears from everybody,” Bryan Raymond said. “Because it had been so long since I've physically seen them. You know, you can love your children from a distance, but being able to physically, you know, hug them and give them a kiss and say ‘I love you’ in person is totally different than on FaceTime.”

'Family to us…'

Last week, with Bryan finally on his feet, he and Trinity went back to the hospital together. First, they made the rounds of the building, stopping over and over again to thank the people who’d cared for them.

“I just couldn't believe how many of the nurses that were there that we knew that became family to us. We did sandwiches and cookies,” Bryan said.

Later that day, Bryan settled in for what everybody hopes is his last surgery, with Meguid operating to correct acid reflux. It’s a condition many Americans handle with over-the-counter medication but it can cause a cough and lung irritation and, in Bryan’s case, that could lead to rejection of the new organs.

Bryan stayed in the hospital overnight and Meguid stopped in to check on him. It would be their last meeting before the Raymonds headed home. The doctor and patient chatted about doing a telehealth visit and about the regular trips Bryan will make back to the Colorado hospital for monitoring. And they talked about what they’d meant to each other over the last few months.

Meguid told Bryan his fight and recovery are an inspiration and a lesson for others.

“You as an individual are inspiring for me to see and for me to think about,” he said. “But I also use you as an example to patients who don't want to get vaccinated to say, ‘Well, COVID shouldn't be taken lightly. I have a patient who is a very healthy young man with a family who unfortunately had to have a lung transplant and he had to have a lung transplant due to COVID.’ So it shouldn't be pooh-poohed, taken lightly and people should get vaccinated.”

From Raymond, there was profound gratitude.

“You saved my life,” he told Meguid. “I mean, not only you but your whole team, and I can't thank you enough for that because if you weren’t there I don't know if I would be here today. And not only is it you, but it's also the donor … We don't know the donor’s family, hopefully, one day we hope that we get to meet them. And, you know, they had to go through something terrible for me to live. But yeah, for me and my family, we can't thank you enough for what you did for us.”