Kelly Murphy said it’s been a tough few weeks for the community of families at STEM School Highlands Ranch.

On June 15, a jury found one of the former students accused of a shooting at the school guilty on 46 counts, including murder. Murphy said sitting through the trial and verdict “crushed” her — but that feeling was only compounded in a Zoom meeting that same night where she and others described feeling powerless that no one on the STEM board, the school’s governing body, is listening to them about their deep concerns about the school.

Murphy is one of a group of 440 parents, students, and community members who want to remove the executive director of the school, Penny Eucker. They accuse her of creating a toxic workplace culture based on fear that they say goes back years. They say that’s led high numbers of teachers and administrators, who say they’re afraid to speak up, to resign.

School officials say the high turnover rate is nothing unusual — especially among charter schools, and given the school’s history of the 2019 school shooting followed by a pandemic.

“This is not what our community needs,” said Murphy on the Zoom call with about 60 other parents. “We need leadership at our school who are going to listen to us and who care about us and who care about our kids.”

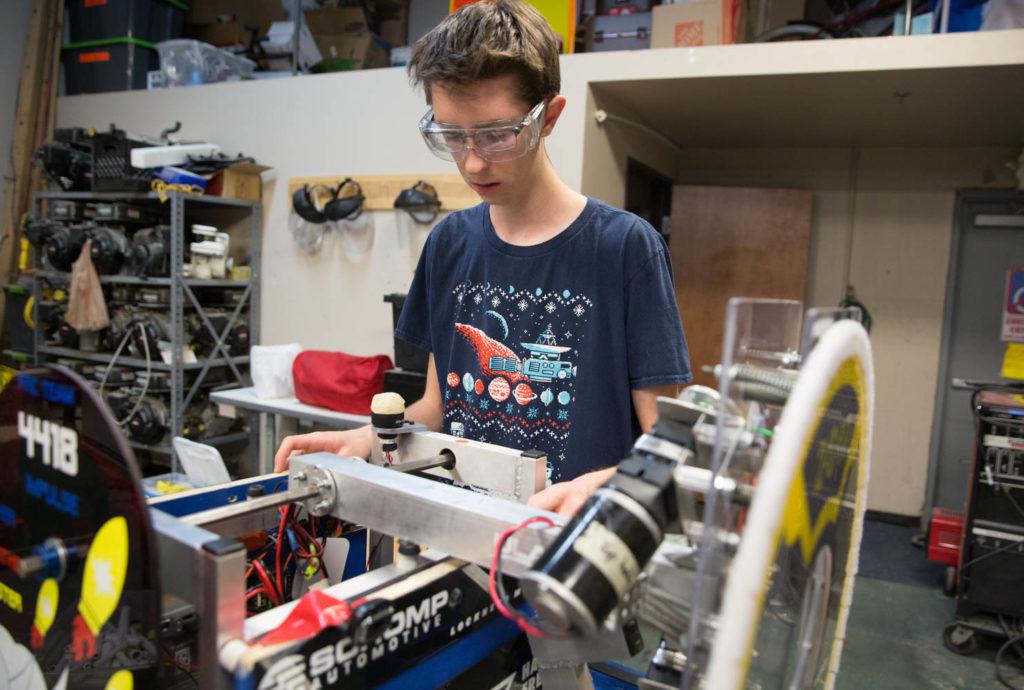

STEM School Highlands Ranch consistently rates among the highest-performing schools in the state. It serves an important role teaching bright and sometimes quirky students who like to innovate and create. But it’s also had its share of problems over the last few years: fights with neighbors over expansion, how special education is taught, the 2019 shooting there and previous calls for the school to part ways with Eucker.

This time around, organizers say more than 400 parents and students signed a petition and letter of concern calling for the STEM board to remove Eucker. It was sent to the board June 1. Eucker has led the school since 2012, a year after its founding. The group, Concerned Parents for STEM, has collected pages of comments from former employees that detail an environment of fear, uncertainty, favoritism, and retribution for speaking up.

For an hour, parents and students spoke one after the other about their concerns during public comment at the STEM board’s May 4 meeting.

Almost 40 percent of secondary teachers left the school this year, 35 percent of them resignations. The school said teacher turnover in all grades is 18 percent. In Douglas County, charter schools that have a physical location for instruction averaged 21 percent turnover among teachers in 2020. Some who left are highly specialized computer science and engineering instructors.

Eight out of 10 administrators left this year — five of them in the middle of the school year, and the latest last week. Only one counselor is returning.

“Entire high school departments have left at the same time,” said parent Quinn Perkins. He said all of his two sons’ favorite teachers have left over the past several years. Everyone his older son, an incoming senior, was going to ask for college letters of recommendation is gone. Perkins doesn’t know if he should start looking for other schools.

“The clock’s ticking on my kids, I can’t just throw away entire years of their education waiting for the school to get their act together.”

“The sheer magnitude of the numbers of people leaving is really telling that there’s something amiss,” said parent Kristen Engelsen. “It’s just mind-boggling that the (STEM) board can look at it and say things are fine.”

Eucker’s contract says STEM has the option of extending her agreement for a final year beyond July 31, 2021. Eucker told CPR her contract runs through 2022.

The STEM Board did not respond to multiple requests from CPR to verify this or to respond to parents’ concerns. The board stated in a May 26 letter to families that it will spend the summer working on addressing their concerns.

“The sheer volume and depth of this month’s ongoing feedback require more effort than usual to deliver responses,” the letter said.

Eucker said teacher retention is a top priority. Building a so-called teacher care model is a main goal of the school’s strategic plan adopted this spring. It includes increasing the number of teacher coaches, more professional development and improving mentoring and relationship building.

“The majority of teachers are remaining,” Eucker said. “STEM remains the home of many on staff with national reputations of excellence in teaching … next year will be a return to what we do best, joyful learning for students and teachers … Our school has had two incredibly difficult years and I am focused on leading us back to calmer waters where every student and staff member can succeed.”

Parents say the same type of complaints about Eucker and a fear-based work environment go back years.

Documents obtained through open records requests show students and an anonymous teacher in 2016 decrying the “mass exodus” of teachers and alleging “inconsistencies, lack of leadership and fear of retaliation.” Eucker’s performance evaluation for that year notes that, “staff turnover continues to be higher than typical for a school going into its sixth year of operation.”

This time in 2021, parents say teachers asked them for help, as they were too afraid to raise concerns publicly.

“The overarching philosophy from the executive director is that there's no real care nor concern for individuals, which then creates that culture of fear,” said one former administrator who spoke with CPR News.

All staff members who spoke with CPR News did not want to be identified for fear of jeopardizing their career and fear of retribution.

“It’s that lack of concern for the individuals in a time of great distress, right? It’s not that the lack of care was new but it is two years out from a school shooting and in the middle of a pandemic and you're watching the world around you of bosses and leaders lean in to take care of their staff and you're watching your boss do the opposite,” the former administrator said. This person said they, and other administrators, left because of Eucker’s leadership.

Another former staff member, who asked for anonymity because she fears retribution, says every time suggestions to improve staff retention or advocate for students were brought to Eucker, she was “dismissive, and very like, ‘Get with the program, you’re here at STEM or you’re out.’” Their suggestions were often rebuffed, she said. Other former employees confirmed that.

“Here is what I have learned: When you speak up at STEM, you are silenced, removed, or made so uncomfortable that you have to leave,” one former staff member said.

Other staff recounted multiple staff members who suddenly lost their jobs, sometimes not even having the chance to say goodbye. Another said entire departments would turn over from year to year, well before the school shooting.

Teachers pushed for a staff feedback team several years ago “because people were scared to talk to administration,” according to another former employee. “The very fact that that group even existed was because of this culture of fear.”

Teachers allege that speaking up results in retribution — either their contracts aren’t renewed or they are fired. One former staff member said there is a feeling that teachers are disposable, and they can be let go at any point for any reason.

Eucker said teachers do not report directly to her.

“The reality is that I neither hire nor fire and rely on my leadership team and teacher teams to make selections and recommendations for non-renewal.”

One former administrator who spoke with CPR disputed that.

A school often in the spotlight

The STEM School, located in Douglas County, is a public charter school with about 1,750 students serving Kindergarten through 12th grade. It is consistently one of the highest performing schools in the state, winning national accolades for its focus on innovation and being a catalyst for creativity. Many gifted students have said they thrive in the fast-paced learning environment.

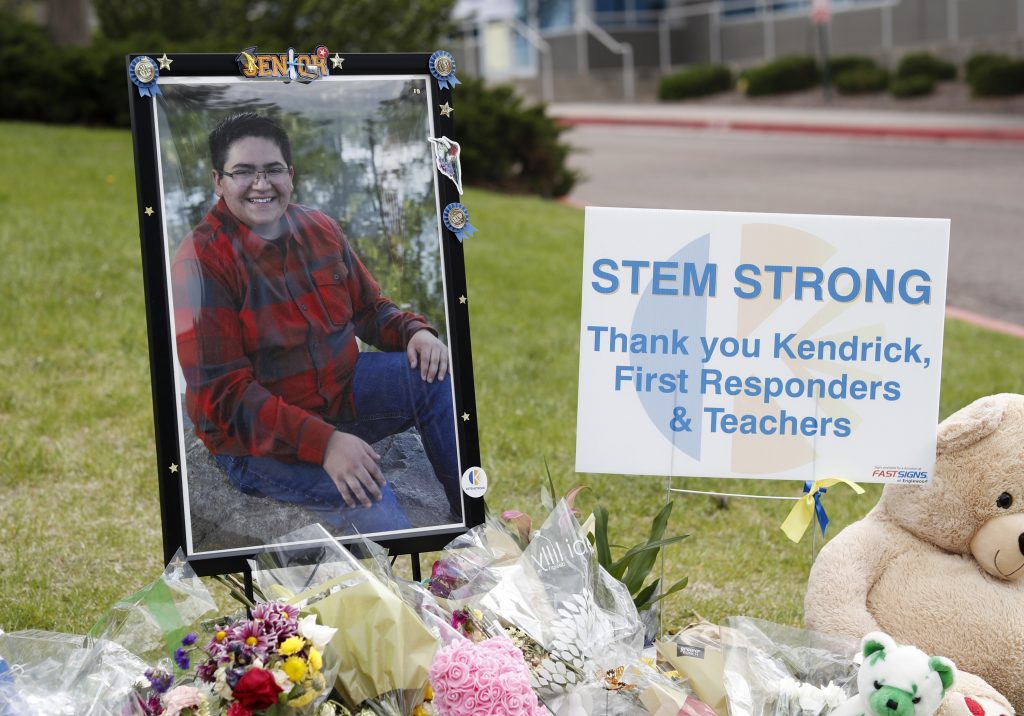

At the same time, the school has had its share of crises - from strained relationships with neighbors over expansion plans, findings of civil rights violations against special education students, fights with the school board over the charter’s renewal and calls for Eucker’s removal at various junctures over the past several years. A school shooting in 2019 caused more destabilization.

In a 2018 letter to the STEM board, the school district admonished STEM for thwarting parents’ legal access to their children’s records and the treatment of special education students and requested action from the school to fix its “ineffective leadership” in these areas and to consider replacing Eucker.

STEM responded with a 6-page letter refuting many of the claims. On the charge that STEM had “ineffective leadership,” the STEM board responded: “To us, Dr. Eucker’s accomplishments are irrefutable evidence that she has engaged in the very acme of ‘effective leadership.’”

Current troubles: the STEM School’s narrative.

Eucker attributes this year’s high turnover rate to COVID-19 and the 2019 shooting at STEM, which left one student dead and several others injured.

“STEM had a double dose of stress with May 7 (the day of the shooting) followed by COVID (a year later),” she said.

Eucker said one reason is the fact that 60 percent of teachers wanted to continue teaching remotely last November. District-run schools, following county health metrics, had closed their doors. Most STEM parents, on the other hand, wanted their children to be in-person, she said.

She said the board directed her to open the school, fearing families would leave for other charter schools.

“I believe we made the right decision,” Eucker said. “It was not a popular decision, and this is the fallout from those who decided to leave.”

She acknowledges she could have done a better job of communicating the decision to the staff, as she said the school was not given advance notice from the district on what its plans were. Eucker said she encouraged staff to apply for and maximize their health and disability benefits if they did not want to teach in person.

“However, this was not seen as a desirable option for some who wanted the only option to be to teach remotely,” Eucker said.

Teachers said they felt devalued by one of the options: “seek other employment.” In a letter, Eucker said grocery clerks and flight attendants “found the courage to report to their jobs.” The letter didn't sit well with some staff, who had acted to protect their students during the school shooting.

“To imply that we lack the courage to report to our jobs is unprofessional, insulting, and offensive,” a teacher wrote in a letter responding to Eucker. The letters were provided to CPR by Concerned Parents for STEM.

Eucker said STEM’s high turnover is not unusual for charter schools because teachers are young and don’t have tenure. Among Douglas County’s 16 brick and mortar charter schools, STEM’s turnover rate ranges from the fourth highest in 2015-16 and the sixth-highest in 2017-18, to the second- and first- (tied) highest in the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 school years, respectively.

Eucker said the pandemic compounded teacher stress. She points to one national study that shows one in four teachers said they were ready to leave the profession.

But longtime parents like Karyn Weiffenbach said that’s not the case here.

“The vast majority of our teachers that are leaving are remaining in teaching, they are teaching locally. They just aren’t teaching at STEM anymore. If we are doing our best to keep our faculty, we are obviously failing miserably.”

Weiffenbach spent a lot of time digging into the retention issue in her role on the school’s strategic planning committee. She’s seen copies of exit interviews from veteran teachers. They cite workload and burnout, lack of support and the work culture.

Eucker agrees a top reason that teachers leave is performance stress, but she points to parental expectations, like “when parents bombard our top-flight faculty and send them brutal email that makes them want to quit,” she said in a school parent forum.

STEM said monthly teacher surveys show staff are satisfied. In areas they aren’t, like with the almost 40 percent who felt uncomfortable going to administrators with help or questions, the school says it’s working to improve things.

The school said it also has an independent human resources consultant who is collecting all exit interview data, to review and use to make improvements.

“For those who just got too beat up in a COVID world, maybe it’s best for their mental health to find what makes them happy,” said Eucker during a school forum with students. “But those who are returning, the expectation for all of us is that we return to a positive, supportive, nurturing culture next year.”

Teachers and administrators say neither COVID, the shooting nor parents are why they left.

Former teacher Beth Gisi, who left the school this year, said that neither COVID, nor the shooting, nor parents had anything to do with her decision to resign from the school. Gisi said she had hoped one day to retire from STEM, and she still has a child who goes to school there.

“I worked at STEM for 8 years and returned to the same hallway, same classroom right alongside many colleagues after the shooting,” she said. “It is heartbreaking to leave the STEM family as a teacher, but for now I remain as a parent who hopes that we can make change.”

Gisi found a culture change driven by school leadership and the board of directors was no longer a match for her.

Eucker said STEM teachers are also recruited by others in education and industry. She said administrators, in this time of massive job transition, often leave for other opportunities. She said there are four new administrators of other schools who cut their teeth at STEM.

“I am proud that STEM was their incubator,” she said.

One former administrator disagrees with that assessment.

“To change culture from the middle was impossible. Penny is why I left. I don’t agree with her ethics, and don't like how she was treating people,” the administrator said.

Several other former staff members also said neither COVID, nor the shooting, nor parents were why they left. They said they were not recruited. They sought other jobs, even at lower salaries, because of Eucker and the desire to be in a positive culture.

“If there was good culture, I'd stay,” said one. “I’d do it in a heartbeat for these kids.”

STEM is also dealing with other issues: Financial pressure on the school increased after the 2019 shooting.

One former staff member said teachers and administrators sensed Eucker’s primary focus was “money and numbers, like, ‘I don’t care if the teachers leave, we just need to keep the students.’”

Eucker stated emphatically that she does not believe that. She said keeping a school open requires being a good steward of the funding the school receives “while providing a world-class education and competitive teacher salaries.”

The school lost 170 students after the 2019 shooting, though it said it has big waiting lists now in several elementary grades. The enrollment drop means fewer state dollars and pressure to do what Eucker calls “right-size.” It boosted the number of classes secondary educators will teach next year to seven, reducing planning time. (Most high school teachers in district-run schools teach five classes.)

“We have to be very careful with how we staff to make sure we are sustainable,” Eucker told students at a forum. The jump in the number of classes taught upset many teachers, who said they are already working around the clock.

Parents also question Eucker’s $278,000 salary, as the executive director of a single school. They note that it is more than any superintendent in the area makes, including at Cherry Creek, Douglas County or Denver. Eucker said it’s what the board offered her after a national comparison of her degrees, skills and “ability to move STEM to premier national ranking.”

Some teachers also allege there was a lack of empathy and care for traumatized teachers and students after the 2019 shooting.

Susanna Spear is a former first-grade teacher's aide who also had children at the school at the time of the shooting. She and other former teachers said they didn’t feel supported and leadership discouraged teachers from talking about it, comforting each other or comforting students.

“A lot of the teachers I worked with had a very hard time with Penny and they were told not to discuss the shooting and all of them left before the next year because they could not handle Penny,” Spear said. “It was just really discouraging.”

Spear said when she voiced her concerns about Eucker at the end of last year, she lost her job.

Some teachers who asked for extra mental health support were asked to bring a note from a therapist certifying that they were fit to teach.

“It made a lot of people afraid,” said one former employee.

“It also made me feel broken, like I was viewed as being damaged,” said another. The feeling staff got from Eucker is that “people should be ‘over it’ after six months or so,” according to one former administrator.

Eucker said caring for her staff’s mental health has always been one of her highest priorities. She said after the shooting at STEM, she encouraged staff, students and the community to access mental health benefits funded with a $3 million grant through AllHealth.

Eucker said she did not discourage staff members from talking about the shooting, but following guidance from the AllHealth team, cautioned teachers to direct students to mental health providers in the school to make sure that they were receiving the resources needed.

What’s next? Parents say they don’t know.

The 400 parents and students who want Eucker out, many of whom have defended the school in past battles, emphasize they want the school to succeed — they just don’t know how that can happen with the current leader. The lack of board response has left parents “frustrated, angry, and disappointed,” said parent Heidi Elliott.

“The community around STEM, all of these parents, the things that kids do at STEM, Penny Eucker is not singularly responsible for all of that success,” parent Nikki Baird said. “That comes from the kids, and that comes from the teachers.”

Baird said the hard part for many parents about speaking publicly is they don’t want what they say to be used against the school in the future.

“It’s a risk that we’re taking to get together and be public about this,” Baird said.