Ask Imam Abdur-Rahim Ali how much policing he wants in his Northeast Park Hill neighborhood and he will say it depends.

Ali doesn’t like when he hears stories of someone getting pulled over for something he considers frivolous. He doesn’t like when African-Americans in the area, like himself, feel harassed or treated condescendingly by officers. This happened when he was driving limousines to and from Denver International Airport years ago.

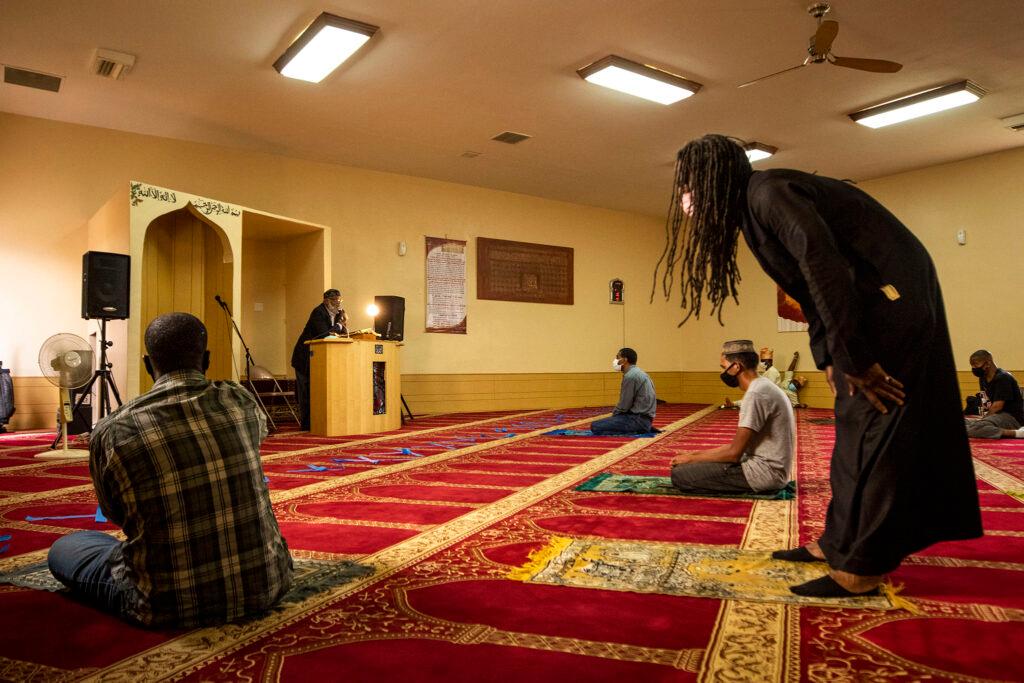

But in his time running an Islamic center, Ali has also called on police.

Like a few years ago, when a white man pulled up in front of his mosque at 34th Avenue and Albion Street, rolled down the window, pointed his finger in the shape of a gun and screamed, “Death to you all!”

Then, there was a federal bulletin he received in January that warned mosques to be on alert for potential terrorist activity surrounding the Inauguration. Ali called on Denver officers to make their presence known — particularly on Fridays when people gather to worship.

Ali is cautious when talking about his own internal tensions: he is both wary of the police and supportive of them at the same time.

“It’s a difficult job and balancing act for the police. We know that but that’s their job.” Ali said. “If you have someone who has criminal intent, we want the police to stop them.”

A year after George Floyd’s murder and the summer of protests that followed, law enforcement agencies and communities are currently amid a Goldilocks-like reckoning about how police do their jobs.

What approach is just right in terms of policing in a neighborhood like Northeast Park Hill? Will residents feel safer with more patrol cars rolling around? Or will they feel harassed and less safe?

In 2020, after Floyd’s death, Denver officers made 70 percent fewer stops in this neighborhood than in previous years. During that same time violent crime in the area — homicide, aggravated assaults and burglaries — jumped 126 percent, according to data analyzed by University of Colorado.

“The police are always tinkering,” said University of Colorado sociologist and criminologist David Pyrooz, who researches DPD statistics. “The only thing you see consistent in policing is change.”

He points out that how police conduct their jobs in communities often comes after people demand change.

“You see this hydraulic shift that exists between the community and the police until the police roll out another form of policing,” Pyrooz said.

Fewer stops and more crime

Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen said the drop in police stops in Northeast Park Hill in 2020 was more a product of staffing challenges than a change in strategy after Floyd’s death.

Pandemic-driven budget cuts meant the agency hired 97 fewer officers in 2020 than originally projected. At the same time, the department staffed dozens of evening protests throughout the summer — a deployment that absorbed patrol officers from other parts of the city. And, Pazen noted, many officers were sickened with COVID-19 or had to go and were out on rolling leaves because of exposure.

When asked whether he believes there was a correlation between the drop in police stops and the increase in violent crime, Pazen said it was “a factor, not the factor.”

“Good policing makes a difference. Good policing does involve reducing traffic accidents, reducing auto fatalities, getting guns off the street,” Pazen said. “But you have to do it in a fair way as well that’s not over-policing … It’s a difficult line to draw at a time when people may be demanding different approaches.”

It’s not just Park Hill that’s seen more crime since the start of the pandemic. Statewide, there were 29 percent more homicides in 2020 compared to the previous year. Property crimes and auto thefts also soared.

In Denver, the increases are particularly stark. Citywide, business burglaries are up by 143 percent, carjackings are up by 140 percent and homicides are up 81 percent since 2019.

Pyrooz said making conclusions about what drives crime rate jumps is complicated, and he can’t say for sure there is a connection between the frequency of police stops and the number of crimes that occur.

“(But) these two things happen simultaneously,” he said. “All signs point in that direction. The timing works … There is an effect, there is a correlation.”

A long career in a changing neighborhood

Denver’s District Two Commander Kathy Bancroft has been with the department since the 1980s and is now in charge of cops patrolling Park Hill.

In her time in the neighborhood, she’s seen big jumps and plummets in crime rates — particularly around the gang wars of the 1980s and 1990s.

Bancroft has also adapted to various kinds of policing, depending on what the community needs at the time.

Over the years, that has included a focus on “community policing” — in which a higher police presence comes with an effort to create relationships with businesses and neighbors. Or “saturation policing” — throwing a raft of law enforcement resources at a high-crime community.

“Saturation policing is what worked in the past,” she said, as she walked around the intersection of 33rd Avenue and Holly Street, in front of a newly refurbished catfish restaurant and an older establishment called the Horizon Lounge. “You’d see these spikes in different neighborhoods and we’d go in with everything we had … and then you’d see another neighborhood with a problem and we’d go in with everything we had.”

Bancroft acknowledged there is no appetite for that right now — despite the alarmingly high violent crime rates that continue into this year.

In her patrol area, Bancroft said she’s had 17 reports in the last 28 days of felony menacing with a gun. Citywide, Denver has seen a 64 percent increase in gun-related crimes this year compared with a three-year rolling average.

The commander continues to make 10 to 20 traffic stops a day in the area — mostly she gives warnings to slow down around schools — because she believes it makes the neighborhood safer.

“We have to be smarter in how we do policing,” she said.

Bancroft, who is white, shared the widespread disgust in Floyd’s murder and agreed with the officer’s second-degree murder conviction, but said the backlash against all officers, including herself, has been surprising.

“At some point, I became accountable for every police officer in the United States,” Bancroft said. “I’m responsible for myself and I’m accountable for what we do.”

But she has welcomed the renewed discussions about policing and police conduct within DPD.

“Those conversations need to be had because I’m not a Black person. I don’t know what that feels like, what that means to somebody, what this uniform means to somebody,” she said. “I think it does need to change and I think we need to have conversations about everything that happened in the past to get us to a better place.”

Police reform an issue locally, and statewide

State Sen. James Coleman grew up in DPD’s District Two and hears from constituents about how much policing and officer presence they want in Denver.

It’s also an issue he has first-hand experience with. He recently saw an African American teenager at the Green Valley Ranch recreation center wrongfully handcuffed and accused of a crime. And he has had "the talk" with his young twins — though they aren’t yet teenagers — about how to act when and if they’re ever stopped by police.

Still, Coleman doesn’t believe anyone in any community wants less policing, despite some talk about defunding the police last year.

“I don’t care what your skin color is, I don’t care what your experience is, no one says, ‘we just want less police here,’” he said. “I think the concern is, if there is a need for police, how they engage and interact and that data is reported.”

Lawmakers have aggressively tackled police reform in the past two years, passing a sweeping bill in 2020 that made it easier for officers to be sued, changed use of force rules and required body cameras for all law enforcement officers across the state.

This year, lawmakers continued their reform march; one new law overhauled misdemeanors and another makes it clear that police can use deadly force only as a “last resort” in conflicts with suspects.

New approach in high crime areas

In the first six months of the year, police stops remained down across the city, but that may change in a new effort launched by Pazen and his commanders, including Bancroft, that aims to target specific high-crime neighborhoods and add additional police presence.

In analyzing the most recent violent crime rates, Pazen found that just 1.5 percent of Denver’s landmass — five violent crime hotspots — accounted for 26 percent of homicides and aggravated assaults.

One of those neighborhoods is Northeast Park Hill.

He said residents in the targeted areas can expect to see more police out on bikes and on foot patrol, cleaning up graffiti and talking to people. The approach also pulls in other community resources to flood the problem areas — like groups that can help with mental health and housing.

“If we can work on these areas and reduce them, you’re going to save lives, you’re going to prevent harm from the community,” Pazen said.

That’s an approach Ty Allen will be interested in watching from the ground.

Allen opened up Mississippi Boy Catfish and Ribs a couple of months ago in Northeast Park Hill.

He had to call the police a few times last year while he was working on the restaurant, getting it ready to open. He said they were slow to respond. But he had a conversation with officers in the area and that has changed.

Allen said he doesn’t feel like the neighborhood is over-policed or that the residents are harassed by law enforcement.

“Do I feel safe? Absolutely. Do I feel like they’re going to respond now within a few minutes? Absolutely,” Allen said. “I’m not giving praise where it’s not due, but they’ve done a good job.”