Law enforcement officers across the state are increasingly facing criminal consequences under a police reform law that puts greater restrictions on when officers can use force, and holds them accountable if they don’t report misconduct when they see it on the job.

Across the state, district attorneys have filed seven charges since last summer against five officers for failure to intervene and failure to report use of force, according to a CPR News survey of all 22 state judicial districts and an analysis of data from the state judicial branch.

That includes Aurora Police Officer Francine Martinez, who was charged last week with failure to intervene and failure to report use of force after video footage appeared to show her standing by while her colleague, Officer John Haubert, beat and attempted to strangle 29 year-old Kyle Vinson while placing him under arrest on July 23.

Haubert has resigned from APD and faces felony assault charges for the incident.

"I was shocked she didn't intervene."

Face down and bleeding, Vinson was still absorbing Haubert’s blows when he could feel a second officer standing by, holding his arm, but otherwise just watching the increasingly violent scene unfold.

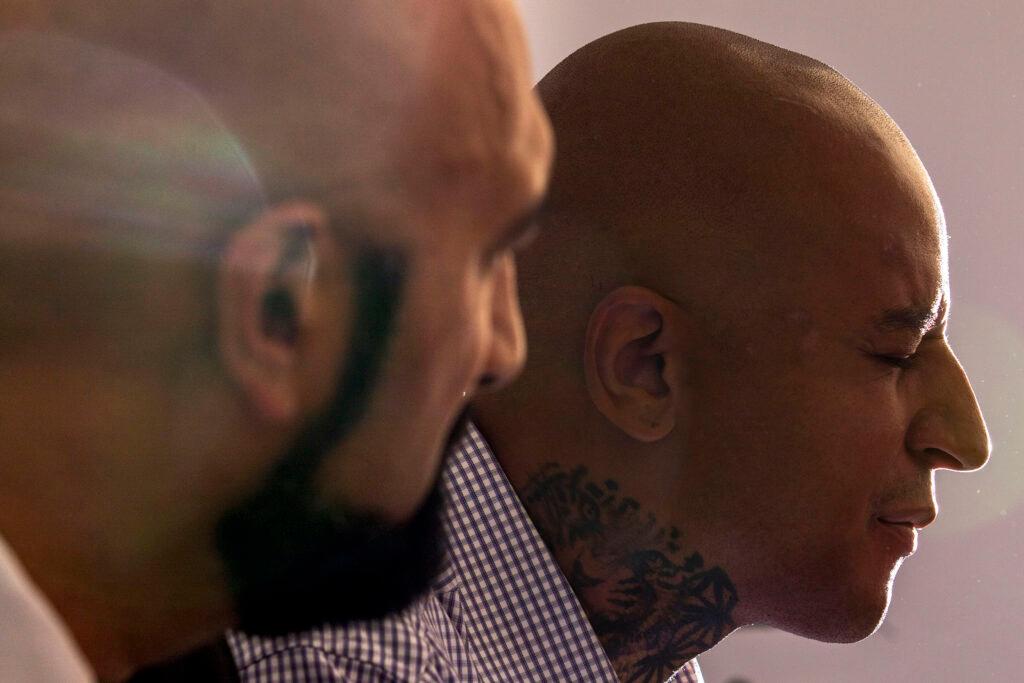

“I was shocked she didn’t intervene,” Vinson said Tuesday in an interview from his lawyer’s office. His lawyer, Qusair Mohamedbhai, said they are considering a lawsuit against Aurora Police. “Why didn’t she just say stop? You see all the blood … and for her not to even say stop … It’s like it gets to a point where it’s almost like a brainwash. Like they just learn to be OK with it. She could just see that happening and she didn’t say stop.”

Prosecutors say that’s exactly what Officer Martinez had an obligation to do under Colorado Senate Bill 217.

The legislation passed with bi-partisan support last summer as a response to the murder of a Minnesota man, George Floyd, who died beneath the knee of a police officer as other officers stood by, choosing not to intervene.

Colorado’s new state law puts greater rules around police use of force, prohibits the use of chokeholds in arrests, and makes it a crime for officers to observe misconduct on the job without reporting it. The law also makes it easier for civilians to sue officers personally for wrongdoing.

Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver, a primary sponsor of the legislation, said she is gratified officers are facing increasing scrutiny -- but lamented those lessons coming with such a cost.

“It is unfortunate that citizens have to go through such traumatic experiences to test out this law,” Herod said. “What we’ve seen is that our police accountability bill is working. Officers are being charged under SB217, whether it’s for excessive use of force in the field or failure to intervene when excessive force.”

How reform is impacting policing

Earlier this year, Herod successfully sponsored another police accountability measure that added some clarifications to the earlier law — including requiring agencies to release body camera footage within a month and prohibiting officers from tampering with body worn cameras when they’re supposed to have them on.

“This is a culture change,” Herod said. “What we’re finding is that together these provisions are working. The community has a better sense of what is going on … Officers are holding each other accountable and agencies are holding themselves and their officers accountable.”

But perhaps more crucial than the handful of additional officers charged in the last 12 months for failing to stop misconduct on the job is the quiet acknowledgement among prosecutors, law enforcement officers and advocates that the new laws are changing the culture of policing in Colorado.

“We’ve been talking about duty to intervene,” said Aurora Police Chief Vanessa Wilson, who said her office worked through a weekend with the Arapahoe County District Attorney’s Office at a breakneck pace to investigate the two officers involved in Vinson's arrest.

Those officers were arrested within five days and the body camera footage was released at the same time.

“We need to make sure our officers have the tools to know exactly what to do in this situation,” Wilson said. “The goal of this ... is to prevent misconduct.”

Since the law’s passage, and Floyd’s murder, prosecutors across the state have filed charges against officers for on-duty conduct that ranged from assault to strangulation.

They acknowledge that many of these crimes existed before the police reform movement -- but that the scrutiny on law enforcement officers has heightened awareness of police behavior.

“It didn’t necessarily create all new crimes, but it gives us additional things to consider,” said Weld County District Attorney Michael Rourke. “It’s just additional pieces of the analysis.”

Rourke filed a second degree strangulation assault charge against Greeley Police Officer Kenneth Ammick in June for allegedly using a chokehold in an arrest. Chokeholds were banned under the legislation passed last year. Two officers reported Ammick’s conduct and an investigation was launched.

Rourke has also refused to clear a Fort Lupton police sergeant who turned off his body-worn camera during an officer shooting in April. The officer has refused to participate in interviews or explain what happened.

“I’m going to leave it open. This investigation will hang over his head until he cooperates or I’m out of office,” Rourke said. “It would have been a concern for us prior to the passage and signing of this bill and it remains a concern of us after it was signed by the governor.”

Body cam footage helping with accountability

The passage of the new law coincides with the expanded use of body-worn cameras by officers and deputies. They will be mandated for all agencies by 2023, but in the departments that use them, they already are providing valuable evidence on the occasions when officers or deputies cross the line.

In Idaho Springs, Clear Creek County District Attorney Heidi McCollum in July filed assault charges against an officer for inappropriately using his taser on a 75-year-old man. That officer was also fired from the force. Footage from body-worn cameras at the scene provides crucial evidence in the case that otherwise might not have existed.

“Would my office have filed this before Senate Bill 217? I certainly hope we would have,” McCollum said. “It’s hard to say what we would have done without both law enforcement and my office being on this heightened level of scrutiny and heightened level of observing officers’ actions. At the end of the day .. this law has made officers’ actions more pronounced.”

A Boulder sheriff’s deputy, Christopher Mecca, also faces criminal charges for misusing a taser on an inmate at the jail. Officials watched body-worn camera footage in that incident to build their investigation, according to the arrest warrant.

Adams County District Attorney Brian Mason’s office filed the first failure to intervene charges against two deputies, Chad Krause and Michael Montgomery, last year because neither stopped another colleague, Andrew McCormick, from allegedly assaulting an inmate in the Adams County Jail last August.

Mason called the new law an important message for the law enforcement profession.

“I think it’s important for us to say not only will we not tolerate this kind of behavior but we won’t tolerate these people standing by and watching it,” Mason said. “Time will tell how impactful it is … I think the entire criminal justice system is under scrutiny more than it was before and I think that’s a good thing.”

- As Crime Rises In Denver, One Historically Black Neighborhood Considers What It Wants From Police

- From Bond Hearings, Court Fees To Ketamine — Colorado Has A Lot Of New Criminal Justice Laws

- Colorado Reformed Policing After George Floyd’s Murder. This Year, Advocates Had A More Difficult Time At The Legislature