On a recent Wednesday night, about three dozen Asian Americans from around Denver gathered at banquet tables in a side room at Twin Dragon restaurant in Englewood, a southern suburb of Denver. They’d come for an Asian Eats club meeting. But while they were anxious to dig into the food, that wasn’t the only thing on the agenda.

“We’re really excited about the turnout. And how excited you must be to learn about redistricting,” Annie Guo VanDan joked to the crowd, before launching into a pitch about why they should care about the complex political process.

VanDan is president of Asian Avenue Magazine. And she is one of many local leaders spreading the word about redistricting in Colorado and what it will mean for communities of color.

That said, VanDan admitted she didn’t know a lot about how it works herself until recently. “For me, this whole process has really been enlightening. And now that I learned so much, I feel my role is to educate more people in our community.”

For the dinner event, she teamed up with community organizer Joie Ha, chair of the Denver Asian American Pacific Islander Commission.

Ha wants the Colorado’s AAPI community to know that getting counted in the Census was just the first step in the process toward full political representation. Now comes the harder part — getting individual people to explain to the commission what makes them a community of interest, and how that should be reflected in the new congressional and state legislative maps.

“The biggest thing I want folks to know is that redistricting is about power,” Ha said. For minority groups — power comes from numbers.

Having enough people in a district helps ensure “you have more power in voting and things like that,” she said. “So with redistricting, what happens is districts can be ‘packed’ or they can be ‘cracked,’ especially for minority influence.”

Packing is when maps overly concentrate a minority community into a limited number of districts — potentially restricting their influence in Congress or the statehouse. Cracking is when maps divide up a strong minority area, diluting their influence.

For Ha, history provides a clear cautionary tale: LA’s Koreatown. In California’s 1990 redistricting, Koreatown was split between many districts. And then came the 1992 LA riots, when many Korean American shopkeepers lost businesses.

Ha noted that when the community tried to get help with cleanup and recovery after the riots, “elected officials all passed (on) the responsibility because they said, you know, Asian Americans didn’t make up a significant portion of their district. And it was because Koreatown itself was split into all these different districts.”

According to the 2021 Census, about four percent of Coloradans identify as Asian or Pacific Islander. But in some areas of the state, like Aurora and Centennial, East Asians and South Asians can make up as much as 40 percent of a neighborhood, and that can have a big impact on something as small as a state House seat.

When it comes to Congress, AAPI voters have been primarily concentrated in CO-06, the Aurora based district represented by Democrat Jason Crow. But as Colorado’s number of Asian American residents has grown, the community has begun to spread out.

VanDan worries about those families who have settled outside the sixth, in suburbs like Highlands Ranch, “which puts them (in a district) with Capitol Pines and Castle Rock, which are predominantly white communities.” She worries AAPI residents have little voice within the district.

African American groups urge commission to consider historic communities

AAPI groups haven’t been working on redistricting alone; since the draft maps came out, leaders in the metro area’s Black, Latino, AAPI, Indigenous and immigrant communities have been in ongoing conversations about how to ensure equitable representation.

“It’s important that all of us come together and figure out what is fair for each other,” explained Omar Montgomery, Aurora Branch President of the NAACP. “And, if one of us gets elected, how do we also champion their values as well?”

Currently, Colorado’s congressional delegation only has one non-white member — Joe Neguse, who is the son of Eritrean refugees. The Colorado legislature has more racial diversity, although it’s not fully reflective of the state’s makeup. 14 of its members are Latino, which is still below their 21 percent share of the state population, eight lawmakers are Black, and one is Palestinian.

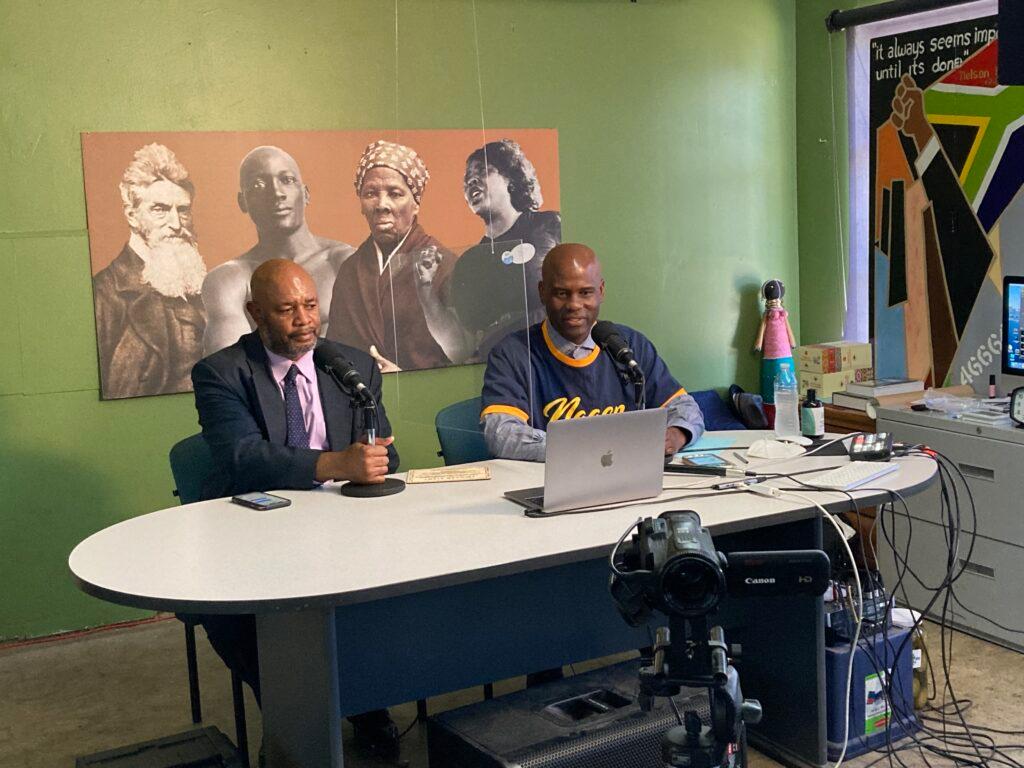

Leaders in the African American community are also trying to get the word out on redistricting; Montgomery was recently one of a number of guests invited to talk about redistricting on a podcast hosted by community activist Jeff Fard, better known as Brother Jeff.

Montgomery told Fard the NAACP is encouraging people to make their views known to the Commissions. “We told our community to attend these meetings, have a voice in these meetings, know the issues, get with your local officials if you haven't seen the maps.”

After spending about an hour on the show, Montgomery stepped outside onto Welton Street, in the historic heart of Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. When he first moved to Denver and asked people where the black community was in the town, they pointed him here.

“People were telling me about the history” when Black workers settled in the area, making it a cultural hub for musicians and entertainers. “They all used to perform here and live right here in Five Points,” he recalled. “And there was a time that Black people couldn't even live in Park Hill. So as Black people began to grow in this city, then they began to move east towards Park hill. And there's a rich history there.”

The proposed statehouse maps would make a major change to this part of town, by splitting the two historic Black neighborhoods of Park Hill and Five Points into different districts. Montgomery worries about what will happen if the community is broken up. The way he sees it, the current maps have led to a good level of representation at the statehouse and congressional level.

“We would like for things to stay pretty much where they’re at — maybe some minor changes — because we’re beginning to see the fruits of that labor of people representing us and representing our values. And it seems like some things are getting done,” he said.

What effect will this input have?

When their first maps came out, the Redistricting Commissions’ nonpartisan staff acknowledged they didn't reflect the various communities of interest — and communities of color — in the state, in part because they were waiting for final census data.

And the process is designed to keep the door wide open for people to champion their communities.

“I don't think that the preliminary map represents ideas that are fully baked around people that have been historically underrepresented and sometimes excluded from our democracy,” said Amanda Gonzales, executive director of Common Cause in Colorado.

For Gonzalez, it’s about fairness and making sure the maps are truly reflective of communities.”If you look at your hometown on that map, does it feel accurate? Are you like, ‘Yeah, that’s where my people live.’ Or are you cut in half?”

Gonzalez is expecting the draft maps to change now that the Census Bureau has released district level results and the commission has held public hearings all across the state. A new map should be released soon.

Whether the final maps give minority communities the power to have equitable representation remains to be seen. But leaders say they’ll continue to speak out and try to get people engaged.

And if it doesn't go their way, they've learned one lesson: the importance of beginning their outreach as early as possible the next time Colorado goes through the redistricting process ten years from now.