Update 5:38 p.m.

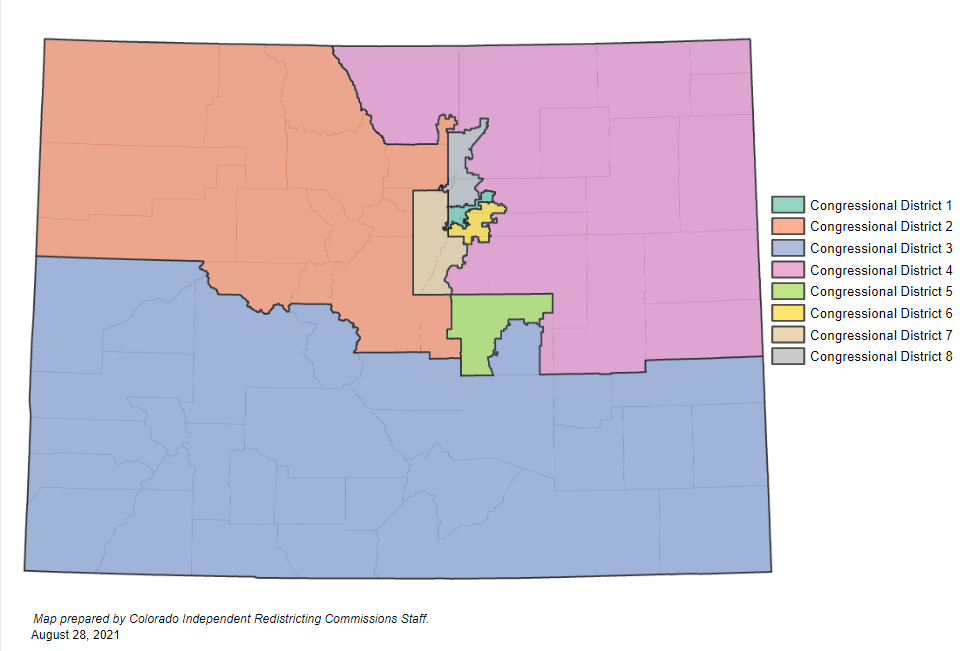

On Friday evening, the redistricting commission released a new proposal for the congressional map. This proposal would move Pueblo and the San Luis Valley back into a district with much of the Western Slope.

Our original story continues below.

Colorado’s redistricting process could lead to big changes for Pueblo and the San Luis Valley, but exactly what shape those changes take is still up in the air.

The region poses a challenge when it comes to map drawing — it’s bound together by a unique identity, but the population isn’t big enough to anchor its own Congressional district.

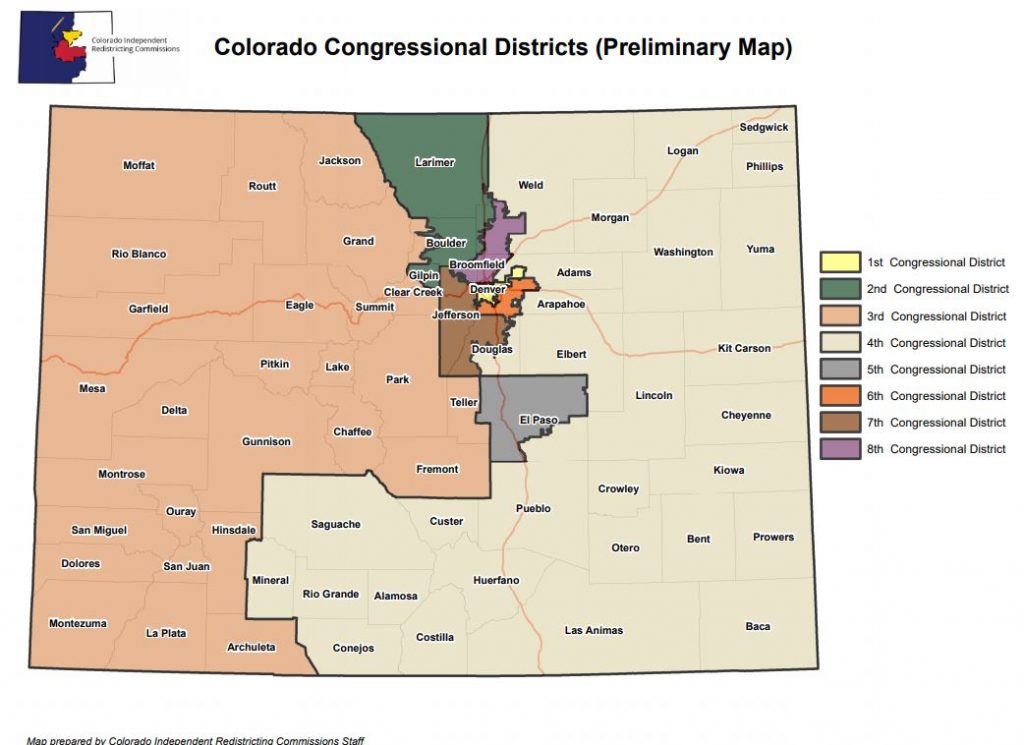

The Independent Redistricting Commission’s draft map released earlier this summer would separate Pueblo and most of the San Luis Valley from the Western Slope for the first time in 40 years, and instead move them into the Eastern Plains-focused 4th district.

The shift has some in the region worried.

“It's almost like we're better with what we know,” said Theresa Trujillo, a Democratic community organizer who has been trying to get Pueblo residents involved in the redistricting processes. All summer she’s been urging regular people to attend public hearings and give feedback about the proposed maps.

One big priority is to ensure the commission understands the historic ties that bind together the sprawling counties of southern Colorado. It’s a legacy Trujillo understands intimately, because her family lived it.

“We are not the folks who crossed the border. We are the folks whom the border crossed and that historic reality, that shared history and the historic neglect that our communities have faced together makes us a significant community of interest,” she said.

Theresa’s father, Saul Trujillo, notes that the region’s Latino residents in particular have moved from place to place over more than a century.

“The migration occurred from Northern New Mexico into the San Luis valley into Trinidad (for) the (coal) mines, Aguilar, Walsenburg,” her father, Saul Trujillo said. “Then that migration moved to Pueblo. And then some of that migration of the next generation moved to Denver.”

Today, more than half of Pueblo County is Latino. The region has also been shaped by other waves of migration; at one point about 40 different languages were spoken at Pueblo’s steel mill, an industry deeply tied to the city’s identity.

Where is the right fit?

Politically, southern Colorado also stands apart from the rest of the state.

Pueblo has more registered Democrats than Republicans, but they tend to be more conservative than voters in blue strongholds to the north. Democratic state lawmakers from the region often go against the rest of their party on hot button issues like gun control.

The county narrowly voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and narrowly for Biden in 2020. In the surrounding region, many of the counties have shifted from blue to red in the past decade, with Saguache and Costilla as the remaining Democratic holdouts in the San Luis Valley.

Whether commissioners stick with their plan of moving Pueblo and the Valley into CO-4, or revert to something closer to the current map and leave it in CO-3, it looks likely the region will remain represented by a Republican in Congress; both districts would be safely red.

But there are a lot of differing views on how the southern portion of the state should be divided. La Plata County Commissioner Marsha Porter-Norton urged redistricting commissioners to keep the San Luis Valley together with the Western Slope, instead of prioritizing putting it in the same district as Pueblo.

She argued communities in the Valley share agricultural, tourism, and public lands interests with southwest Colorado. “I don't see how that way of life has much in common with Pueblo's economy?”

Otis resident Landan Schaffert told the commission he is largely pleased with the current draft map and would be glad to see an Eastern Plains district anchored by Greeley in the north and Pueblo in the south.

“The preliminary map sends a clear message to those in ag that they matter and deserve representation. It also sends a message to those outside of the rural areas that rural Colorado is a priority,” Schaffert told the commission in written comments.

While Pueblo County is partly urban, it is surrounded by agriculture to the east and south, from potato crops in the San Luis Valley, to cattle ranches and dryland farming south and east. And of course, there are Pueblo’s famous green chiles.

The Musso family farmstand a few miles outside of downtown Pueblo was crowded on a recent weekday morning. Cars filled a small dirt parking lot and the road leading up to it was lined with cars. The first Musso to farm here bought the land when he immigrated to the region from Italy. It’s passed down through four generations so far.

People who come here are focused on the produce and prepared foods, not politics. Most said they aren’t really aware of the redistricting process going on, or its potential impacts for the area. But they do have a strong sense of regional pride.

Erika Springer moved to Pueblo from out of state about a decade ago. She said one thing to know about this place is how much people appreciate their community.

“The people that live here are extremely proud, like where they're from and this town,” said Springer. “They are such welcoming people and I thought there were a lot of new experiences [here].”

A political conundrum

The tricky part of redistricting in Southern Colorado comes down to math. The nine counties the commission is considering moving from the third district to the fourth have a combined population of 225,794 people. Since each Congressional district must have as close to 721,714 residents as possible, whatever district they end up in, they make up about a third of the population.

“There's only so much that they can do,” said Republican former statehouse Speaker Frank McNulty. He is the registered agent for the Colorado Neighborhood Coalition, which has been advocating for congressional maps from a conservative perspective.

“The numbers are what the numbers are, if you’re going to respect Denver and keep Denver whole, and you want to keep El Paso county as whole as possible.”

However, there are proposals on the table that could radically change the map, in part by breaking up Colorado’s two most populous counties — Denver and El Paso.

The Latino advocacy group CLLARO floated the idea of an east/west line from Utah to Kansas to create a southern Colorado district. And one commissioner has also asked the non-partisan staff to draw a southern district to see how it would shift all of the other proposed seats.

Simon Tafoya is a Democratic commissioner who represents Denver on the body, but grew up in Pueblo. The changes he requested would also shift the balance of power between the parties, compared to the staff’s map. The southern district would still be quite Republican, but overall, the Congressional delegation would likely split 5-3 in favor of Democrats instead of a 4-4 split.

However the lines fall in the end, leaders in southern Colorado hope a final Congressional map doesn’t dilute their unique voice, at the state capitol or in Washington.

“There needs to be significant changes… that’s undisputed,” said State Senate President Leroy Garcia, a Pueblo Democrat, of the draft maps. “And you hear the commission saying, ‘we're listening. These are not going to be the final maps.’ So we know that. So now the question is, well, how do we get to a map that better serves those communities?”