Colorado’s Eastern Plains saw a lot of rain in the spring, which helped half of the state escape drought.

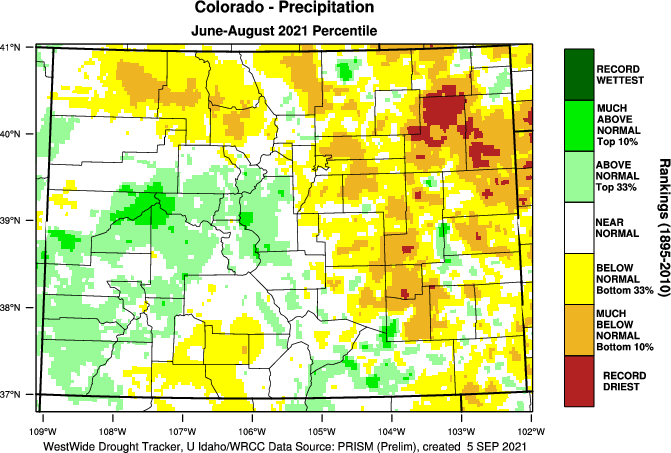

Summer was a different story. Many areas got much less rain than normal, and some spots around Washington and Yuma counties recorded their lowest amount of precipitation on record.

Now drought has started to creep back in.

State climatologist Russ Schumacher said a weather station in Akron recorded its second-wettest spring, followed by the driest summer recorded there.

Joel Schneekloth, a regional water resource specialist with Colorado State University Extension, said if the extra spring moisture had been met with average summer rainfall, it would have been a “fantastic” year for many crops.

“The lack of rainfall really hampered us,” Schneekloth said. “I'm actually somewhat surprised at how well the earlier planted summer crops we're doing most of the summer.”

Schneekloth said the “saving grace” of this summer for the plains was the wet spring and closer-to-normal temperatures meant farmers used just a little more water than average. He said that made the biggest difference compared to historically dry summers in years like 2012 and 2002.

Schneekloth said the amount of water used to keep crops alive in 2002 was unlike anything seen before for the area, and he hopes it won’t ever be seen again — especially since the Ogallala aquifer is drying up.

“To put it bluntly, we have too many wells pumping water that the system can not recharge fast enough to meet those needs,” Schneekloth said.

The wet spring meant most corn growers in Washington County will likely have a better year than they did in 2020, Schneekloth said. The county’s average corn crop yielded around 15 bushels per acre in 2020, but that average could increase to 35 this year.

What’s hurting the most this summer is proso millet, which was the third-largest crop for Washington County, according to 2017 data from the USDA.

“In our area for the most part, it’s a disaster,” Schneekloth said.

The millet is planted in early June, and the area’s last good rain was weeks before that. Schneekloth said the shallow roots failed in the dry soil. Those dry soils will have a long-term effect going into the fall because they will make planting wheat before the winter tough, Schneekloth said. He hopes some rain will fall before then.

“We like to have something in the bank going into the fall,” he said.

Ron Meyer, an agronomist for Colorado State University Extension, said the extreme rain helped some crops on the Eastern Plains.

Meyer worried there wouldn't be any wheat to harvest after a dry fall and winter in 2020 and into 2021. But the moisture got the wheat-growing again in March, which resulted in an above-average crop.

Once it stopped raining again in the summer, spring-planted crops like corn, sunflower and millet are now struggling.

Meyer said the dry summer shows why it’s important for farmers and ranchers to adapt to a warming climate. One way is through “banking” soil moisture by adopting practices that promote soil health and reduce tilling, as well as using drought-adapted varieties of crops to improve their chances of having a good harvest in extreme conditions.