Unlike most gardeners, Danica Lombardozzi doesn’t look for tomatoes and cucumbers at the end of the summer. The climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research instead searches her “ozone garden” for brown and black splotches.

“Damage tends to get pretty severe by the end of the growing season in Colorado,” she said. “That’s a little bit scary to me because it means there’s been a lot of ozone.”

The garden is tucked near the entrance to NCAR’s Mesa Laboratory in the foothills above Boulder, Colo. On a hot, smoggy September afternoon, Lombardozzi visited to collect data on plant damage, which wasn’t hard to find.

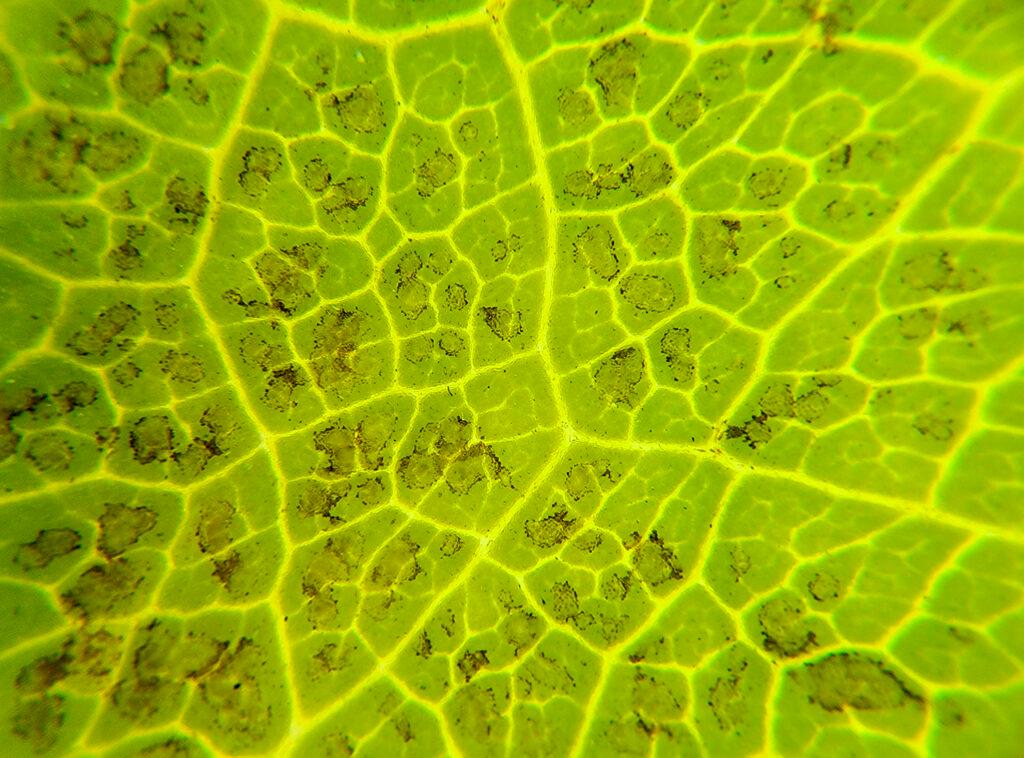

Broad surfaces of some milkweed leaves had blackened. A careful look at the Rocky Mountain cutleaf coneflowers revealed a matrix of brown speckles.

Each sickly plant hinted at a summer of bad air quality along the Front Range. Along with wildfire smoke, the region has seen a spike in ground-level ozone. The invisible pollutant forms when heat and sunlight hit a wide range of other pollutants, kicking off a complex chain of chemical reactions. The tiny garden is filled with ozone-sensitive species, known as bioindicators, so that people can see clear evidence of the problem.

The plant bed is more than an educational stop for public tours. It’s part of a national network of similar plots helping scientists understand how ozone hurts vegetation — and weakens one of the planet’s best natural defenses against climate change.

To understand the connection, Lombardozzi said it’s important to focus on the role of carbon dioxide. Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, humanity has pumped the greenhouse gas into the atmosphere through the combustion of fossil fuels. As concentrations of the gas have increased in the atmosphere, so has the planet’s average temperature.

Vegetation luckily relies on the same gas for photosynthesis. As a result, one estimate found plants absorbed about a third of all the carbon dioxide people have emitted from burning fossil fuels over the last decade, helping blunt the impact of total greenhouse gas emissions.

“Plants perform this incredible service to help maintain our climate,” Lombardozzi said. “They take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and put it in their leaves.”

The problem is ozone irritates plant airways just like it bothers human lungs. On the bottom side of all leaves are tiny holes known as stomata, which take in the pollutant. Once inside, a single pesky oxygen atom, known as a radical, breaks off the larger ozone molecule and irritates the cell membranes inside the plant.

To save itself, the plant closes its stomata. Lombardozzi said this process damages individual plants throughout her garden and makes it harder for whole forests and grasslands to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

It also means plants could be even more efficient carbon sinks. A 2020 study found just a 50 percent reduction in ozone precursors from the transportation and energy sectors would boost photosynthesis enough for vegetation to reabsorb all the carbon dioxide released from wildfires. If humanity completely eliminated its ozone problem, plants could lock up 15 percent more of the greenhouse gas, researchers found.

The carbon-absorbing potential is why the choking plants in her garden don’t entirely depress Lombardozzi. The damage to a critical ally against climate change are wounds people could probably heal.

“It’s a double whammy,” she said. “If we reduce ozone pollution, we will be able to breathe easier and we are helping to reduce the carbon dioxide that’s in our air because our plants can grow bigger and store more carbon.”