Even as some of its vehicles fill with passengers for the first time in more than a year, the Regional Transportation District does not plan to bring back a significant amount of service anytime soon.

One big reason is a familiar one for many businesses and services returning from COVID-19 slumps: The Denver-area transit agency does not have enough bus drivers and train operators.

"September was a substantial increase for us,” Jessie Carter, RTD’s manager of service planning and scheduling, said of a 6 percent service increase the agency made earlier this month. “And it is challenging our current headcount.”

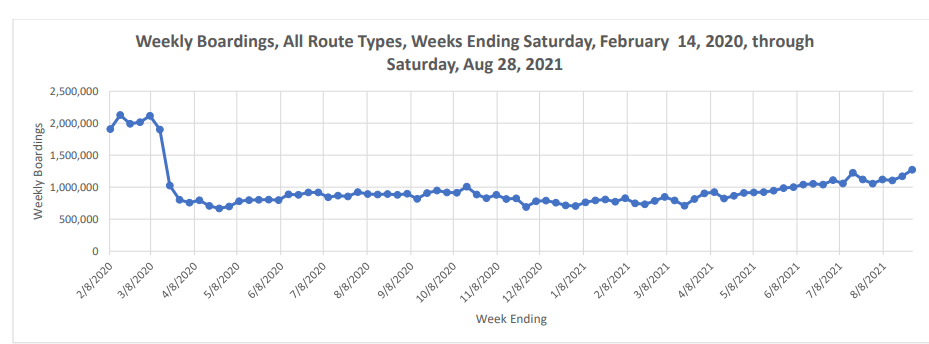

With this month’s change, RTD is now offering about 70 percent of its pre-pandemic service levels. The next proposed change, in January 2022, is modest. Ridership is about 1.25 million passengers a week, roughly half its pre-pandemic levels.

Ridership can be significantly higher on certain lines, like the Flatiron Flyer rapid bus lines between Denver and Boulder. Some buses have been packed since students returned to the University of Colorado late last month, Carter told the RTD board on Tuesday.

"I am quite encouraged by the ridership increase that we've seen,” Carter said. “And if we had the resources available to do so we would be looking at implementing more of the Flatiron Flyer.”

RTD staffers told the board they are stepping up hiring efforts, including new hiring and retention incentives.

A shift away from forced overtime was welcomed by drivers, but RTD is struggling to hire quickly enough.

After a scathing state audit earlier this year, RTD executives say they will no longer mandate overtime to keep service levels up.

That practice, which RTD employed for years, led to high staff turnover and missed trips prior to the pandemic. RTD cut service by about 40 percent in response to the pandemic in the spring of 2020, and for the first time in years, had the staff it needed to operate without forced overtime.

The shift away from mandated overtime is “admirable,” said Lance Longenbohn, president of the ATU Local 1001, which represents most bus and train operators. But he said RTD is not hiring quickly enough to build its ranks.

"There is an uptick,” he said in a phone interview. “But at the same time, we still have people leaving."

Pay is a top issue, Longhenbohn said. Driver wages now start at just over $20 an hour. Fast-food restaurants in the Denver metro are offering wages just below that, Longenbohn noted, and can be much less stressful than driving a large, sometimes-crowded bus through traffic.

Longenbohn said the union will push for a “substantial” wage boost during the next round of negotiations on its contract, which expires in March 2022. RTD needs to do that, he said, to keep up with private sector companies that are offering generous signing bonuses and big pay hikes to their drivers.

"The companies that are smart aren't messing around with this,” Longenbohn said.

Manpower is a big issue now, but money woes are present too.

Federal pandemic-era rescue grants of nearly $775 million are helping RTD keep buses and trains rolling as the agency’s main revenue streams — sales tax revenue and fares — fell last year.

More federal money could trickle down through President Biden’s infrastructure bill and the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill, but the fate of those measures is not yet certain. In the meantime, revenues aren’t high enough to bring back service to its pre-pandemic level.

The agency has another large set of bills coming due: a $290 million maintenance backlog for things including new buses, building upgrades, light rail equipment and more.

"If we could spend $10 per minute, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, just on our current backlog, it would take us over 55 years just to get the organization back to zero," Lou Cripps, RTD’s senior manager of asset management told the board on Tuesday.

RTD must budget for both maintaining the current system and working on unfinished big projects.

RTD needs to balance — and perhaps favor — the need to maintain its current system with unfinished expansion projects from the 2004 voter-approved FasTracks plan, Cripps said. The agency is under intense pressure to finish one line from that plan in particular: a 41-mile, $1.5 billion diesel-powered commuter rail line between Denver, Boulder and Longmont.

“These numbers are sobering,” board member Shontel Lewis said of the maintenance backlog, adding that RTD should show them to local government officials and taxpayers who’ve clamored for RTD to finish FasTracks.

"Are you suggesting we get a billboard, maybe, up on [U.S. 36] there that has this information on it?” board member Kate Williams of Denver asked wryly, referring to the main highway between Denver and Boulder.

The backlog is factored into the agency’s financial plan through 2027. The RTD board recently voted to spend $8 million on a new study of the unfinished Denver-Boulder-Longmont train and hopes to partner with the state and federal governments to cut costs.

But a presentation to the board Tuesday shows that even without any more expansion, the FasTracks budget needs propping up. Debt service payments eat up about half of the FasTracks revenue, which is one key reason its budget is forecast to be underwater by some $226 million through 2027.

Staff are now proposing that RTD’s base system, which includes nearly all of its bus network and its older light rail lines through downtown Denver and the south metro, subsidize the FasTracks budget. CFO Doug MacLeod said the agency always intended to shift money that way at this point in time — but it could mean less money for base system buses and trains.

“It’s very clear that the base system is heavily subsidizing FasTracks to get a balanced budget,” said board member Peggy Catlin. “Sorry for my editorial comment.”