There’s lots to do in Branson, Missouri.

There’s comedy shows, theme parks, an Elvis impersonator and —

Wait a second. I’m being told this story’s about Branson ... Colorado?

Uh, what can you do there?

“Zero restaurants. Zero gas stations. It’s in the boonies,” said Gavin Sanchez of Trinidad, who commutes 50 miles to Branson (the Colorado one) for school every day.

Sanchez, 17, is one of just a few dozen students who attend Branson School, the only one in this remote ranching town in Las Animas County. The southernmost town in the state, you can probably walk to New Mexico from Branson without breaking a sweat.

Aside from its single K-12 school, the town has a church, a post office and some farm equipment. That’s about it.

Fifty-seven people live here. Including high school senior Brody Doherty.

“There's more dogs in town than people,” Doherty said. “You get to know everybody’s names and everyone’s grandma, so it's one big family.”

When asked if he also knows everyone’s dog’s name, Brody said, “Pretty much, yes.”

So yeah, Branson’s tiny. But it’s got itself a pretty darn good high school football team.

With only 17 varsity players on its roster— and that’s with the help of players like Sanchez who commute to Branson from out of town— the team is much too small to fill a regular-sized football team roster. So, the Bearcats play 6-man football, where most everyone plays offense and defense.

Playing on both sides of the ball can get a little confusing too.

“(Coach would) put me on offense. I like defense a lot because I don't have to memorize all these plays,” said Gavin’s brother Brendon Sanchez, a sophomore. “And coach’ll tell me to do something and I'll be like, ‘What?’ And then I'm like, ‘Coach, what’s this?’ And he’s like, ‘You're supposed to memorize this!’ And I’m like, ‘I don't play this position!’ And he's like, ‘Well you're gonna have to start playing!’”

When you’re playing football with six a side, flexibility is key, these players say. “Everyone needs to be able to play every position,” said Peyton Cranson, a star running back for the Bearcats. “Everyone is eligible for a pass and everyone needs to be an open field tackler.”

Cranson, who lives southeast of smalltown Kim, Colorado, has to drive one and a half hours to go to school in Branson each day.

“It’s the closest school I can go to,” he said.

Branson athletic director Brad Doherty, the father of Brody Doherty, the team’s starting quarterback, said the Bearcats’ closest opponent is two hours away.

“That’s normal for us,” he said. “We drive 50 miles (to Trinidad) for gasoline and groceries, so you plan your week around your grocery and gasoline run. But it's just the tradeoff you make. You also get to run and hike and play and go for bike rides and truck rides and you don't have to worry about traffic or people. You can let your boys run and let your dog off the leash and just have fresh air.”

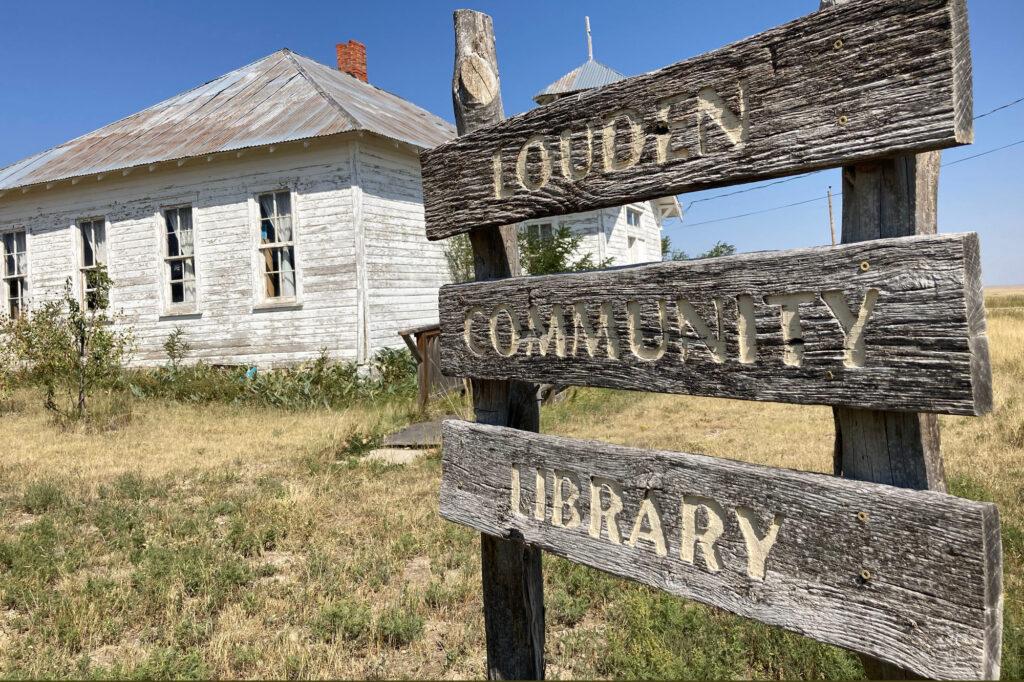

If You Don’t Build It, They Won’t Come

Until recently, the Bearcats had largely gone unnoticed by most of the world. That was until a group of opposing coaches refused to play in Branson anymore— because of their field.

The coaches were worried that their players would get hurt on what’s been described as the worst football field in America.

“It was all dirt,” said Gavin Sanchez. “There were a bunch of gopher holes and snake holes.”

When asked if any gophers would pop up while they were playing or practicing, Sanchez said, “Actually, yes. We actually had a gopher come to the field and we had to smoke him out and get him taken care of.”

Head coach Adam Lucero said the Bearcats’ playing surface was more cow pasture than football field.

“That’s exactly what it looked like, except I think we had a little more cactus around here,” he said. “We turned it into a football field as best as we could but there were a lot of times I was pulling cactus out of my players’ arms. I’d get ‘em in there myself or you run into a gopher hole and twist your ankle.”

Branson is located in a region Brad Doherty describes as the “high-low plains,” a high desert-like part of the state that gets little precipitation. The town gets its water from five springs from nearby mesas that don’t provide nearly enough water to maintain a garden, much less a football field.

“It would take about 60,000 gallons of water to take care of a football field,” Doherty said. “Our town springs produce about 15,000 gallons a day.”

“So we were just hoping and praying that it somehow would grow, but we just couldn't keep it up,” he said. “Even with prairie grass or drought-tolerant grass and whatever we happened to have growing, we couldn't beat the (low) moisture or the groundhogs.”

So, the team needed a new field. Problem is, they didn’t have a few hundred thousand dollars laying around to pay for it. The Branson School District is one of the poorest in the state, with more than half of its students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunches.

So, Brad Doherty reached out to some local TV stations to try to drum up support for a campaign to raise money for a new field.

And the news spread faster than a gopher being smoked out of a hole.

Local news organizations started doing stories on the team. Pretty soon, the Bearcats were getting attention from national news outlets who couldn’t resist doing stories on the so-called worst football field in America.

As attention grew, so did donations.

“Every day I would log into PayPal and it was amazing,” Brad Doherty recalls. “Log in in the morning, new thousand dollars. And then you log in at lunch, and another five to six thousand dollars. I had it set to notify my phone and I had to turn those off because it was dinging all hours of the day. It was overwhelming.”

Money was coming in from all over the place: California, New York, even the United Kingdom.

After the campaign launched in January, hundreds of thousands of dollars was raised in just a few months. Brad Doherty said as of last week, the school had raised $500,000.

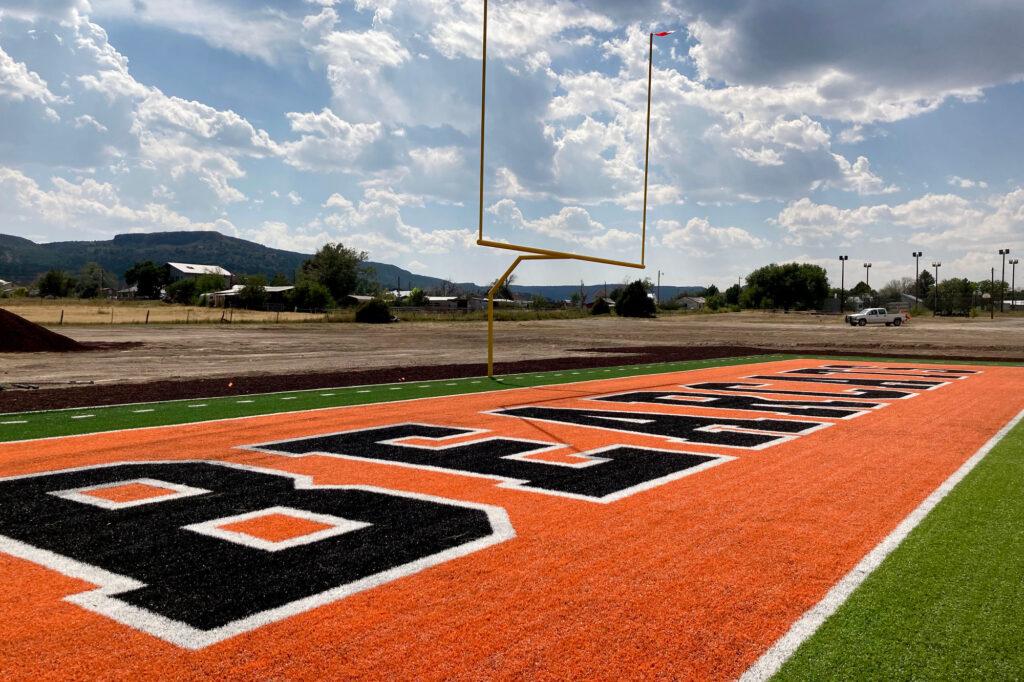

Now, this town of 57 people and a few more dogs has one of the premier football fields in all of Colorado: Fancy green Astroturf that doesn’t need watering. End zones painted in the team’s orange and black colors, with a big bad bearcat logo at midfield.

A half-million-dollar Field of Dreams in a town that doesn’t even have sidewalks.

“People heard that story and helped these kids out,” Coach Lucero said. “I know we don't know ‘em. They may live in a different continent — literally we had donations from Australia — but they saw human beings in need and I think when it comes down to it, we all pulled together in that sense.”

‘Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Can’t Lose’

This past Saturday, the Bearcats hosted their first home game of the season, debuting their new field to a few hundred out-of-town spectators who watched the game in folding chairs or from the backs of pickups along the sidelines. Kids were selling homemade slushies for $3.

Many fans wore orange shirts with the phrase, “Clear eyes, full hearts, can’t lose,” a nod to the TV series about high school football in small-town Texas, “Friday Night Lights.”

The Bearcats ran onto the field behind a player waving the American flag. A pregame ceremony paid tribute to 9/11 and the military service members who were recently killed at an airport in Afghanistan.

Branson’s opponent, the Deer Trail Eagles, were no match for the mighty Bearcats, who won the game in a blowout. Besides, there was no way Branson was gonna lose the first game on their new field, one that wouldn’t be here without the generosity of others.

“This happened right in the middle of COVID and we launched this (fundraising effort) right after the inauguration and all the political craziness there,” Brad Doherty said. “So this was the only good story in America happening. So many positive messages. I’m getting goosebumps talking to you.”

Rita Jaquez, clad in an American flag shirt, watched the game from under a canopy tent on that hot Saturday afternoon. Jaquez has worked as a janitor and bus driver at a nearby school in Kim for 50 years. She often transports students to and from Branson and has known many of the players since they were little kids. Heck, she’s known some of their parents since they were kids.

She couldn’t believe her eyes when she saw the field for the first time.

“I [saw] a comment on my Facebook that the Denver Broncos will be at some football games,” Jaquez said. “And I posted back that they ought to come to Branson.”

Maybe that’ll be the next big thing Branson does. Because clearly, this town can do anything.

Eat your heart out, Branson, Missouri.